President Trump’s pandemic relief executive orders are limited in scope

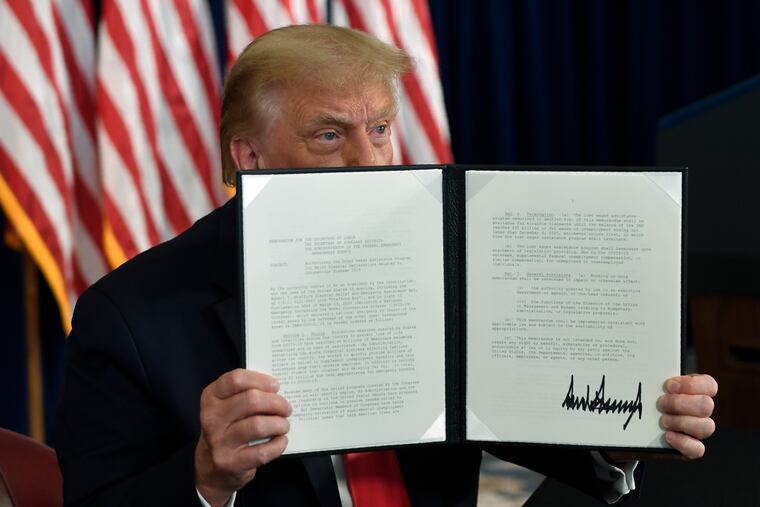

The executive orders signed by President Donald Trump to help Americans cope with an economic recession are far less sweeping than any relief bill Congress could pass and raise questions about effective they will be

NEW YORK — President Donald Trump’s new executive orders to help Americans struggling under the economic recession are far less sweeping than any pandemic relief bill Congress would pass.

Trump acted Saturday after negotiations for a second pandemic relief bill reached an impasse. Democrats initially sought a $3.4 trillion package, but said they lowered their demand to $2 trillion. Republicans had proposed a $1 trillion plan.

The are questions about how effective Trump's measures will be. An order for supplemental unemployment insurance payments relies on state contributions that may not materialize. A payroll tax deferral may not translate into more spending money for workers depending on how employers implement it.

But the president is trying to stem a slide in the polls with a show of action three months before he faces Democratic challenger Joe Biden in the November election.

Here is a look at the four executive orders.

Unemployment insurance

The president moved to keep paying a supplemental federal unemployment benefit for millions of Americans out of work during the outbreak. His order called for payments up to $400 each week, one-third less than the $600 people had been receiving under a benefit that expired last month.

How many people will receive the benefit and for how long is open to question. Trump said the payments would be funded 75% by the federal government and 25% by states. But it is unclear if states will pay that share, given acute budget shortfalls amid the economic recession. The federal government had been covering the full cost of the now-expired $600 supplement.

Ariel Zetlin-Jones, associate professor of economics at Carnegie Mellon University’s Tepper School of Business, said several states have already depleted their unemployment compensation trust funds and have requested federal loans to keep making payments. Trump's order, he said, is likely to exacerbate the debt burden for states and prove costlier in the long term because state governments borrow at higher costs than the federal government.

“This higher debt burden is one reason governors may resist enacting at least their share of $400 promised in the executive order,” Zetlin-Jones said.

The Trump administration is setting aside $44 billion from the Disaster Relief Fund to pay for the extra jobless benefits. Under the order, the payments will last through Dec. 6 — or until the disaster fund's balance falls to $25 billion. With hurricane season now underway, the fund currently has a balance of about $70 billion.

Payroll tax deferral

Under the president’s order, employers can defer collecting the employee portion of the payroll tax, including the 6.2% Social Security tax on wages, effective Aug. 1 through the end of the year. The order is intended to increase take home pay for employees making less than about $100,000 a year. White House economic adviser Larry Kudlow estimated Sunday that the payroll tax deferral could save employees about $1,200 through the end of the year.

However, employees would need to repay the federal government eventually without an act of Congress. Consequently, many employers may choose to continue collecting the tax and set it aside to meet that future obligation, said Michael Graetz, a Columbia University law professor and co-author of “The Wolf at the Door: The Menace of Economic Insecurity and How to Fight It.”

“I don't know how much of this is going to get into workers' pockets,” Graetz said.

Trump is proposing that Congress pass a permanent payroll tax cut, but the prospects of such a measure is uncertain. Democrats and some Republicans are against any change to the payroll tax because it could deplete the Social Security and Medicare Trust funds.

Both programs were already in dire condition before the pandemic, with Medicare expected to become insolvent in six years and Social Security unable to pay full benefits starting in 2035. Those government projections came before millions of taxpayers were thrown out of work.

Trump offered no explanation how the government would fund Medicare and Social Security benefits that the 7% tax on employee income covers.

Eviction crisis

The president did not extend a federal eviction moratorium that protected more than 12 million renters living in federally subsidized apartments or units with federally backed mortgages. That moratorium expired July 25.

Instead, Trump directed the Treasury and Housing and Urban Development departments to identify funds to provide aid to those struggling to pay their monthly rent. He also directed HUD to take action to “promote the ability of renters and homeowners to avoid eviction or foreclosure.”

In an appearance on CNN on Sunday, Kudlow said the order gives the housing authority wide power to stop evictions, for instance by citing the risk of COVID-19 spread in a community. But he acknowledged that it does not explicitly ban evictions.

It's unclear how much immediate relief the order will provide tens of millions of people at risk of being evicted over the next months. Around 30 state moratoriums have expired since May. The Aspen Institute has estimated that 23 million renters are at risk of eviction by Sept. 30.

Housing experts have called for a national moratorium on evictions combined with financial assistance for those struggling to pay rent.

Student loans

Trump's executive order extended a moratorium on student loans backed the federal government, which was initially passed by Congress and would have expired on Sept. 30. The moratorium also forgave interest on the deferred payments.

The order does not cover loans from private lenders since the government would have repay those providers and the president lacks the authority to direct funds for such a purpose. The order also does not amount to student loan forgiveness, which House Democrats have proposed in a pandemic relief package, but which Republican lawmakers have rejected.