How tines have changed: The weird histories of forks and other household goods

Household goods – bathtubs, duvets, fireplaces, pillows, spoons and more – all have a history of how they became essentials in our homes.

The United States has been contemplating the temporary loss of toilet paper (which has been on a cardboard roll as we know it only since 1890, according to Charmin) and appreciating anew what we had taken for granted.

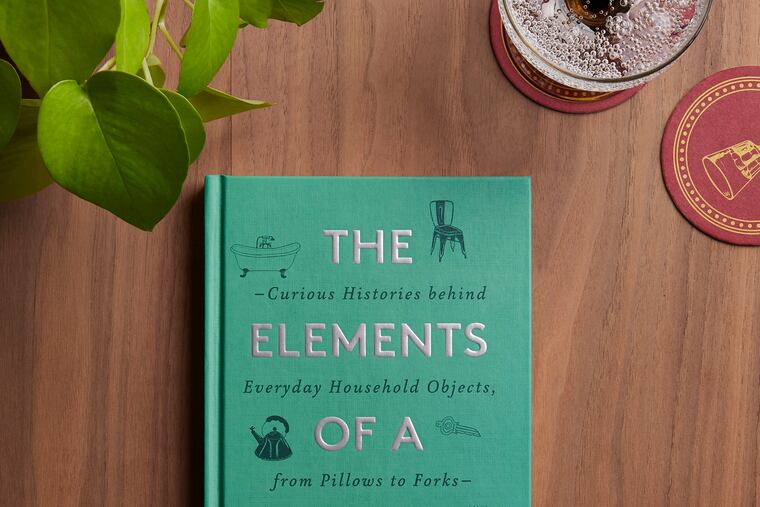

It’s a good moment to count our blessings. Fortuitously timed for those of us suddenly spending a lot of time at home is design historian Amy Azzarito’s new book, The Elements of a Home, on fascinating histories of all sorts of household goods: bathtubs, duvets, fireplaces, pillows, spoons and more.

Azzarito used to write about the history of objects for the popular blog Design Sponge. "This is what we were trained to do," she says, "look closely at an object, an artifact, and zoom out from there and see what it tells us about society and culture." She has a master's in library science and used those skills to page through about 500 books for her research.

"Following the trail is one of the most enjoyable parts for me . . . sitting at my desk with 30 books open, trying to find every reference I can to plates," she says. We talked with Azzarito about the history behind some of her favorite household objects.

The fork

“The fork was certainly one of my favorites” to research, Azzarito says. “This thing that we interact with every single day of our lives was once deemed immoral and unhygienic.” It didn’t help that the early two- or three-pronged fork looked so much like a devil’s pitchfork. Although the first forks were used in the middle of the Byzantine Empire, between 330 and 1453, they weren’t socially acceptable by the rest of the world until sugary, syrupy dried fruit was all the rage with Renaissance Italians. It was impossible to eat while keeping hands and ruffled sleeves clean — unless you used a fork.

"When does the fork get adopted?" Azzarito asks. "It gets adopted when there's a craze for a new sugary treat. Even humans hundreds of years ago had a sweet tooth and were willing to risk their dance with the devil for dessert. And that's how the fork comes back in."

The clock

Before timekeepers were so widely available, clockless factory workers paid "knocker-uppers" a penny a month to knock on their windows in the morning. "Our lives are definitely easier without having to hire someone to knock on your window," Azzarito says.

The history of clocks, of course, starts with ancient sundials, then moves to the first mechanical clock in the year 723. Later, in the 14th century, each town or city had a large public clock that chimed to keep people on schedule. When clocks finally became something of an attainable luxury, Napoleon made sure he had 36 in his chateau — though not nearly enough for its 1,500 rooms.

The bath

After exercising, men in ancient Greece would stand under cold water poured by spouts or servants. They believed strongly in a cold shower being morally superior to a relaxing, warm bath. “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” Azzarito says, noting that cold showers are back in vogue — many argue they’re better for sleep and productivity.

From 1500 to 1700, bathing fell out of favor because medical experts believed that "water opens the pores and allows disease to enter the body," she adds. It was only with the advent of enlightenment thinking that regular bathing crept back into daily life. People started dabbling with baths on a larger scale in the Victorian era, when the Greeks were admired anew. Once indoor plumbing was possible, postwar houses in the 1950s were built with plumbing and hot water, making a steamy shower the experience we expect in our bathrooms.

The sofa

You can thank Louis XIV for a comfortable seat as you binge-watch Netflix. During the Middle Ages, kings, queens and their courts traveled with their furniture in tow from castle to castle. Portability was the selling point. Ten-year-old Louis had to flee Paris to Saint-Germain-en-Laye without his furniture, however, in 1648 because of a civil war, which meant that when courtiers came to visit him there, they had nowhere to sit.

"He was humiliated that he couldn't provide hospitality," Azzarito says. He spent the rest of his life compensating, creating the famous Versailles with comfortable pieces of furniture.

Azzarito’s favorite fact about the sofa, however, is that 18th-century Britons were scandalized by its provocative reputation. (Marketing often showed women lying on them.) “This didn’t keep them from buying the sofas, though,” Azzarito explained. “They’d just move the sofas out and hard chairs in when there was company.”