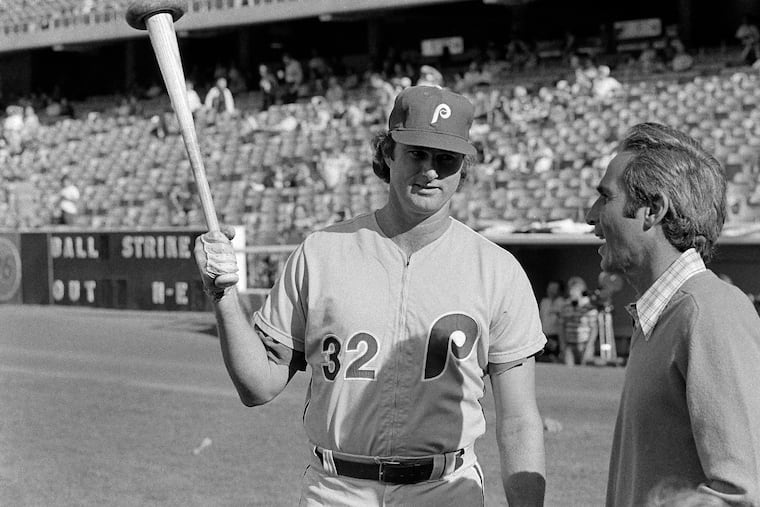

The Archive: The time Steve Carlton talked

Former Phillies ace Steve Carlton doesn't like talking, especially to the media. Here's one of the rare times he did grant an interview.

The distance between the pitcher’s rubber and home plate is 60 feet, 6 inches. Been that way for 125 years.

Not for Steve Carlton.

Carlton wanted to get the baseball to the crouching catcher, past the plate, past the nameless, faceless hitter.

"You stop looking at the guy in the on-deck circle," Carlton said. "You stop looking at the batter. And pretty soon it becomes that refined game of catch I got it down to."

That refined game of catch earned him four Cy Young awards, resulted in 329 victories, in 55 shutouts, in 4,136 strikeouts, and now, a plaque in baseball's Hall of Fame.

“If I can get the ball to the catcher, I have done a successful job,” Carlton said. “Because I’ve gotten it by the hitter. But if you look at the hitter, then your focus stops at the hitter. So now, you only pitch so far. And you’re going to run into trouble.

“I never had contact with the batter. Except Dave Parker, who once jumped back at a curveball and still swung. I had to look at him. Might have been the only time I started to laugh on the mound. It was a curveball on the outside part of the plate, down, a good pitch. Actually, I’d let it go early, started it off way behind him. He jumped back 2 or 3 feet and the ball kept breaking and he swung even though the ball was in the dirt.

"Funniest thing I've ever seen. He put his hands on his hips and he looked at me. And I had to look at him to see what he was thinking. And he had that grin on his face, he didn't know what he had done."

All those innings, all those hitters, and the only eyeball-to-eyeball contact Carlton can recall was that time Parker bailed and then flailed at a curveball in the dirt.

It was the one light-hearted moment in a sprawling, 50-minute interview at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel recently.

Carlton agreed to the session, first establishing ground rules that limited the questions to baseball-related topics.

He had been scorched lately by stories that wandered beyond the white lines. Wary, he agreed to talk because he has a gospel he wants to share, a compelling belief that there is greatness in all of us, lusting to get out, if only our minds stopped clogging the path.

“The conscious mind,” he said, “is the architect of your reality. What you hold in your mind, what you mouth, what you speak, becomes what you are. What you’re thinking about starts the artist to draw the picture. So, if you’re setting yourself up to fail, the architect will draw the picture of failure and you will fulfill that prophecy.

“I’m trying to say something that uplifts society. My words to you are to your readers. They always have been. We’re in a mess because we think ourselves in a mess. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy.”

Carlton arrived in Philadelphia in 1972, reluctantly, in that swap for Rick Wise. He won 27 games for a woeful team. The next year he lost 20 and the cynics wondered out loud where he'd misplaced his positive thinking.

Long periods of parched silence followed, Carlton blotting out the media the way he muffled the crowd noise, the hitter's face and reputation, reducing pitching to a refined game of catch, reducing life to a series of goals to be met, mountains to be climbed.

The trade epitomizes the dramatic changes in the game.

“There were no agents,” Carlton recalled. “You were on your own. Up against a lawyer, a general manager, someone in the corporation. The Cardinals had always told me, ‘You’re not a 20-game winner, don’t bother us now.’ And then, in 1971, I won 20. I said, ‘Well, here I am, I want to be paid.’

“Two years prior to that sort of set up the trade. I’d won 17 in 1969, struck out 19 in one game, had some pretty good stats. I wanted some extra money, maybe a $3,000 or $4,000 raise. Now, they’re making that per at-bat. I held out and held out and held out. Didn’t go to spring training. (Owner) August A. Busch called me in, one to one in his office.

“He was pretty powerful, a man used to getting his own way. He thought I should accept his offer. It got pretty intense. At one point he was pounding his fist on the desk. He really got entrenched in his feelings toward me. Dick Meyer, who was head of the (Anheuser-Busch) brewery, came in to smooth things over and we compromised on a two-year contract.

"In 1970, I lost 19, and the next year I won 20. Mr. Busch was looking at two years, and I had put that other year way behind me and was thinking, 'Well, I've won 20 and I want to get paid.'

“August A. took it personally. Decided to get rid of me, and tried to bury me with a last-place ballclub. Wise and I were asking for the same thing, $67,500. We both wound up getting it. When I heard about the trade, I called (general manager) Bing Devine back, said I’d take their previous offer. He said, ‘Sorry ...too late.’

“When I went into a season, I had my goal set. In 1971, my goal was to win 20 games and I won 20. That’s when I started picking up the mental part of the game. Now, I thought the logical thing to do was boost the victory total. I was with the Cardinals, loaded with talent, deep. So I raised my goal to 25 games.

“Opening day of spring training I’m traded to the Phillies. Traded from a team capable of winning 90 to a team that might win 65. First week I was depressed, in such a dilemma in my mind, because the game had thrown me such a big curve.

"And then, I decided, I'd thought for four months about winning 25, and I wasn't gonna stop. It took a lot of courage to hold onto that goal."

Hold onto it, and surpass it, winning 15 in a row during one incredible stretch, chalking up 27 of Philadelphia's scrawny 59 wins.

“I was never so focused as I was in 1972,” Carlton recalled. “I don’t recall ever throwing a ball over the heart of the plate. Constantly on the corners. Command of three pitches. So incredibly confident.”

Carlton’s confidence splashed his teammates like some heady cologne. They performed better on the nights he pitched.

“That’s how you can influence your environment,” he said bluntly. “Those are the laws of positive thinking. That’s how critical proper thought is. If I hear people talking a certain way that sets a tone for failure, I always point that out to them. I tell them to take the t’s out of their cant’s, things like that. Because the body is listening to you speak.

“Every cell, in my understanding of the body, has a consciousness, and it listens to you. Your life may be miserable, but if you change your mind, you change your thoughts, you change your life. That’s why it’s so important to think proper thoughts. One on one, I’d tell them how to think. Everything contributes to failure or success. I was projecting winning. It was like, ‘I demand that we win.’

“They played championship ball behind me. And I’d tell them, ‘Look how well you played behind me. Why can’t you do that tomorrow? Or the next week or two?’ They would coattail on an attitude and raise their level beyond what they perceived their abilities to be. But when they played beyond themselves, it was really themselves.”

He pitched 346 1/3 innings that year, completed 30 games. He strolled through games like picnics in the park, welcome relief from the martial-arts grind he practiced the other days of the week.

“I’d lifted weights from the time I was 14,” he said. “I was a skinny kid growing up. When I signed, I was 6-3 1/2 and maybe 183 pounds. Genetically, I didn’t look like Roger Clemens. I felt I needed strength. In the ‘60s, you had to fight like crazy against ownership, doctors, trainers, who were against weightlifting. I’ve always had pretty strong hands and that helped the slider. But I had a fine slider before I started martial arts.

“Genetically, you can only throw so hard. Nolan Ryan stands head and shoulders above the rest of us, able to throw 100 miles an hour. Lots of guys are in the 95 range. I was in the low 90s.

“Martial arts was for the endurance, the ability to recover within a day, to pitch again if I had to. There were times after I pitched nine innings, I’d work out with Gus Hoefling the following day. I’d be sore going into the workout and when I came out, all the soreness was gone from my arm.

“I’d gotten rid of the lactic acid buildup, the kind of thing running couldn’t do, by itself. Prior to working with Gus, I’d carry that soreness into the day of my next start. Gus’s training gave me the stamina to pitch in hot, hot weather, without getting tired.

“The day I pitched was a day off from martial arts. It was like a state of euphoria, I didn’t have to work out. The game became, psychologically, and from a physical standpoint, like an easy day. To me, it was a big boost. To me, it was like, ‘Geez, this is a day off, let’s go out and pitch nine innings.’

"To me, it was an attitude. To me, life has always been an attitude. Everything I've done has always been to help me succeed, be it training of the mind, training of the body, or stopping talking to the media.

"That was a way to simplify what I had to deal with. I never took on more ideas, I was always casting off, because you can't be thinking about a lot of things when you're pitching."

For someone who perceived the task as a refined game of catch, it helped to have a simpatico catcher. Carlton had Tim McCarver during his halcyon days.

“Timmy and I clicked so well,” Carlton said. “It was so unlike any other situation. We were so in tune. When a guy came up, we had three pitches in mind we were gonna get him out on. Strike him out. He worked hitters so well, remembered situations. We’d get a guy out on a pitch he liked. We’d get a guy out on a fastball half (the width of) a ball off the corner of the plate.

“When I threw breaking balls, I picked a spot on the catcher to throw to. When I threw at his right shoulder, it would be a slider for a strike. When I threw at the center of his chest, it’d be a slider for a ball.”

The slider, that nasty, devious pitch that baffled hitters, creating all those clumsy half-swing strikeouts.

“Early in my career,” Carlton said, “I didn’t have a pitch that intimidated lefthanded hitters. I threw over the top. Wherever it took off, that’s where it was gonna stay. My curve was over the top and it didn’t have any left-to-right movement. I needed a pitch to move sideways, to intimidate lefthanded batters.”

Fidgety, they'd swing feebly at that slider plummeting out of the strike zone.

“Ferguson Jenkins made a living out of that,” he said. “Every time you swung, it was a ball. If you took it, it was a strike. The spin on the slider was so tight, it looked like a fastball. You couldn’t see a dot on it, couldn’t see the spin.

“You’ve got 98 percent of the people committed to hit fastball. So they see this ball and it looks solid. All of a sudden, they stride to hit fastball. The ball starts to break, explodes at the end. That’s why you see all the checked swings.

"If they don't swing, you throw the fastball on the outside part of the plate and get a called strike. Now, they're committed to hitting fastball and you've got 'em where you want 'em."

As brilliant as that 1972 season was, that's how bleak the '73 season played out. Carlton blames himself.

“I set myself up to fail,” he said glumly. “I went on the banquet trail. Everybody wanted a piece of me. I gave my power away. I let them have their way. I don’t think I ever picked up a weight.

“Winter of ‘72, I was everywhere. Doing everything I shouldn’t be doing. Got to spring training with walking pneumonia. It set me up to have the problems I did. Because I failed a year or two, and it wasn’t really failure, it was a lesson, I don’t believe in good and bad, I believe life is about lessons, and these guys (cynical writers) wanted to tee off on me.

“This is my problem with the media. They chop off the heads of others to make themselves taller. This is where we’re not uplifting society. They have an obligation to do this. To themselves, to their readers. What are they doing to uplift society?

"Instead of teaching society to reach for the next rung of the ladder, they say, 'There are the heroes, let's bring them down. ' To me, that's a sin."

He had three more Cy Young seasons, three World Series starts for the Phillies, before they tearfully released him in 1986.

There were brief stints in San Francisco, in Chicago with the White Sox, in Cleveland, in Minnesota.

“I tried to acquire some sort of a changeup and never came up with anything successful, never got the feel for it,” Carlton said. ”And with the Giants, I tried the split-finger fastball because everybody did that with the Giants. But I didn’t really have the hand for it.

“I tried to make some adjustments, but looking back, I think it was just having eight bone chips in my shoulder. I don’t know if anybody really diagnosed it. I never had rotator-cuff problems, it was just those free-floating bones in my capsule area that Dr. (James) Andrews extracted after I retired from the game.

“After Andrews went in there, he said there was nothing really wrong with the shoulder. Relieved a lot of that nagging pain. He said that some of the chips were so big he had to break them up to get them out of the arthroscopic hole they’d cut.”

Had he blocked out the pain those last couple of years, the way he'd blocked out the crowd noise, the way he'd blocked out the menace of those nameless, faceless hitters?

Was he fooling himself, with the same deceit he'd used on hitters, when he told the media at the Hall of Fame announcement press conference, at age 49, he could still pitch?

"I can still pitch," Carlton said, staring a laser hole in the writer's chest. "Now that the bone chips are gone, I feel confident I could come back and pitch."

The human race, he once said, is the only species that sets limits on itself.

Carlton never did that, never will. He speaks now to deliver the moral to that incredible 27-10 season, the year he came to the wretched Phillies, clutching his goal of winning 25.

"It was sort of devastating," Carlton recalled. "But I said to myself, 'If, indeed, what I believe in is truth, then I must go forward to fulfill how I've been thinking.'

“I held onto those ideas, pulled them off to a higher level. You see the power of thought. The body just follows the mind around. If the mind is idle, if the mind is lazy, and the mind is not thinking correctly, then the body becomes lazy and doesn’t act properly.

"You can cure the body through proper thought. You heal the body. I believe in talking to the body if it's sick, nurturing it, taking care of it.

“It needs direction. It’s a vehicle for carrying you around, your mind, your soul. You must take care of it in proper fashion.”