La Mott in Cheltenham Township hosted the first training camp for Black soldiers in the Civil War

But the area’s role in history was not limited to the war years.

This article originally published in The Inquirer on Feb. 7, 1990.

There is sacred ground at the end of North Broad Street, across Cheltenham Avenue in Cheltenham Township.

Here, in an area now known as La Mott, soldiers of African descent trained to fight in the Civil War at Camp William Penn, established in 1863 as the nation’s first training camp for Black soldiers.

But the area’s role in history was not limited to the war years.

Before the Civil War, it was a major station on the Underground Railroad, and such eminent abolitionists as Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass often met there.

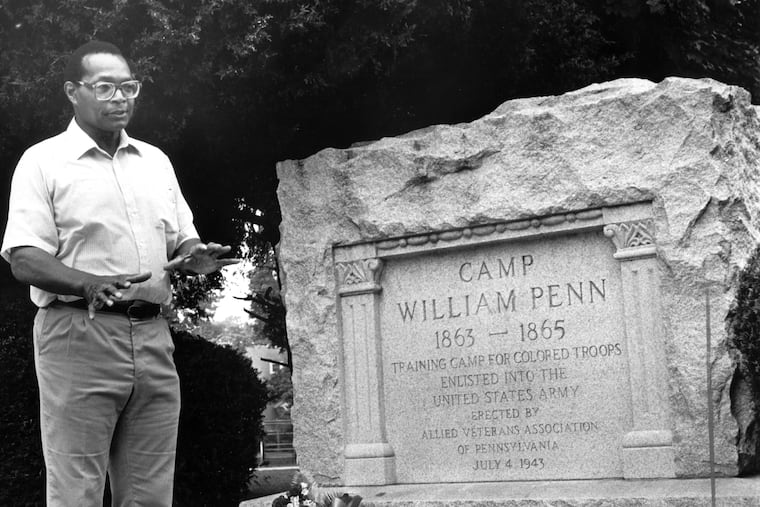

“They (abolitionists) planned a lot of their activities right in this area,” said Perry Triplett, 62, executive director of Citizens for the Restoration of Historic La Mott.

Later, it was an integrated enclave named for Lucretia Mott, a Quaker and outspoken opponent of slavery.

The village, about five by 10 blocks, is bordered by Cheltenham Avenue, Old York Road, Penrose Avenue and Beech Avenue.

Triplett, whose family has lived in La Mott since the 1800s, has led a impassioned 20-year struggle to restore homes and build a visitors center and memorial garden.

The community was designated a historic district by the state in 1985. But the organization is still wrangling with the National Park Service over whether La Mott should be a national historical site, which would clear the way for federal funds.

Standing in front of the black iron gate leading to the old Army camp, Triplett tells a visitor that the ground should be considered sacred and treated as a national treasure, not as a footnote in American history.

Before Camp William Penn was built, African Americans aspiring to join the Union Army practiced in Philadelphia at night to avoid the scorn of whites and the laughter of other African Americans who considered them fools for wanting to fight for a government that considered them less than human.

In 1863, the governor ordered the would-be soldiers, many of them former slaves, to disband. Instead, they left for Boston on a trip paid for by abolitionists and Quakers, to join the 54th Colored Regiment of Massachusetts, the unit featured in the movie “Glory.”

That same year, the War Department established Camp William Penn as a training center for Black soldiers. For the first time, Americans of African descent were officially a part of the U.S. Army.

“You know the president talks about how to stop young people from taking drugs,” Triplett said, pointing to the entrance gate, “but he doesn’t realize that this is what it’s all about.

“Young people need a sense of themselves. They need to know about their history, where they came from and the great people in their past. Then they wouldn’t need drugs,” he said.

Despite a 10-block border with the nation’s fifth-largest city, La Mott bears none of the outward scars of its neighbor.

There is no graffiti in La Mott, no gang activity, no litter on the streets.

The homes, some built with lumber salvaged from Camp William Penn, are neat and well-kept. One can almost feel the pride of the people who live here and walk the quiet streets.

Known as Camptown during the early 1800s, La Mott began to develop in the mid-1860s after the camp was dismantled.

African Americans and Irish immigrants bought small lots from Edward Davis, son-in-law of Lucretia Mott, who encouraged integrated living. The community changed its name to La Mott in 1885.

La Mott’s first school, built in 1878, now houses the Community Center and Free Library; La Mott AME Church, constructed in 1911, sits on the site of La Mott’s first church built in 1888; and of course, there’s Camp William Penn.

Eleven regiments that trained at the camp were considered part of the original forces of the U.S. Army and fought valiantly during the Civil War.

Frank H. Taylor, author of “Philadelphia in the Civil War: 1861-65,” wrote that in 1864, Maj. Gen. Benjamin F. Butler said of the soldiers after one campaign in the South: “Better men were never better led, better officers never led better men. A few more such charges, and to command colored troops will be the post of honor in the American Army.”