Black Opals: How a rare Black Philly literary journal is finding new life

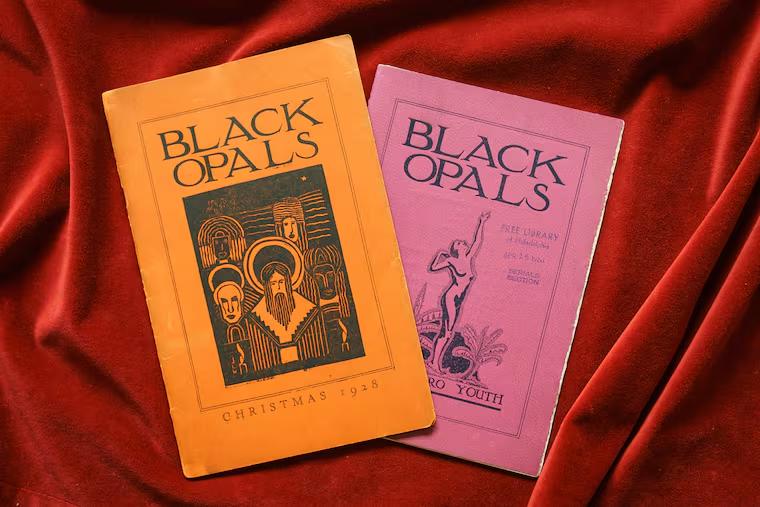

Black Opals, published four times between 1927 and 1928, is finding new readers after nearly 100 years in obscurity.

They were a collective of Philadelphia writers — teachers, students, newcomers to Black literary circles, others well-acquainted with rising stars from Harlem’s artistic milieu. They decided to put out a literary journal themselves. They’d call it Black Opals.

Black Opals ran between 1927 and 1928, at a time when the Harlem Renaissance was in full swing. The name came from the poem “Longings,” by one of their founders, writer and educator Nellie Rathbone Bright.

“I want to feel the rain on my cheek,” Bright wrote, in the poem’s last five lines, published on the first page of the journal’s first issue, “The thrill that comes from a lark’s long note, / I want to see the sky at dawn thru the lacy green of a willow tree. / I want to look deep in a pool at night, and see the stars / Flash flame like the fire in black opals.”

While the publication met its sunset after only a four-issue run, its impact resounds still today. Black Opals is a milestone in a long history of Black Philadelphia writers. It’s also a portal to understanding not only more about Philly’s connections to the Harlem Renaissance, but also how renaissances were happening in other cities.

During a time when many people around the world are reevaluating the ways racial injustice has impacted our institutions, the four issues of Black Opals — a set of which sold for $45,000 at auction last year — are experiencing another life.

This small magazine is now among the top 20 most requested items in the Free Library of Philadelphia’s rare book department, said Caitlin Goodman, the department’s curator. The Free Library is one of only two libraries to have the full run in their collections, the other being the the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library.

“Libraries and collectors are coming to a very overdue realization that their collections have sort of documented white history, white supremacy,” Goodman said, “and they’re suddenly reconstituting their collecting scope to really sort of focus on under-heard or disappeared voices.”

While not as famous as the Harlem Renaissance’s most brilliant stars, the collective that produced Black Opals “did participate in almost all aspects of the New Negro Renaissance,” wrote researcher Vincent Jubilee in his 1980 doctoral dissertation. “[P]ublishing in New York-based Black magazines; socializing with Harlem writers, financing and publishing a small short-lived literary journal; and winning prizes in the same literary contests sponsored by Opportunity and Crisis that brought so much encouragement to the beginning Harlem writers.”

Jubilee hoped his research, which earned him a doctorate from the University of Pennsylvania, would prove that the term “Harlem Renaissance” was a “delimiting misnomer.” The ways of the New Negro — a concept framed by the legendary philosopher Alain Locke — that would embrace education, Blackness, social change, and the artistic output from that racial consciousness didn’t just remain fenced inside Upper Manhattan. Rather, Jubilee explained, that energy spread, inspiring artists in cities like Los Angeles, Washington, Boston, Topeka, and, of course, Philadelphia, Locke’s hometown.

Ninety-five years after their first publication, the small, rareified issues of Black Opals still have an upstart feel. Most issues had only 250 copies and numbered roughly 16 pages. To read Black Opals’ essays, short stories, and a heavy showing of poetry inside the Free Library’s rare book department requires a micro-spatula: a small double-ended tool, thin enough to slide between pages. A couple of the copies are extremely delicate with, in part, tattered pages. Still, the words read clearly, and Black Opals seems like an indie publication pulled together within community.

Goodman likes that Black Opals feels almost like a zine. “It’s an amazing survival,” said Goodman, who estimates that the library may have acquired the pamphlets when they first came out, its issues slowly making their way, with decades and with age, into the rare book department.

“This is something that people can see and touch and feel like they could do the same,” she said. “That is one of the kinds of stories that I really like to help make happen here. Because it’s accessible. And it’s repeatable. Like you could go home, and you could start this.”

In contrast to Harlem, which drew creatives from different backgrounds and different origins within the diaspora, Philadelphia’s Black literati mostly hailed from the same social stratum — Black elites with ancestors who’d been in Philadelphia for generations, Jubilee noted. Many had attended the same schools, like Central High School, the Philadelphia High School for Girls, the University of Pennsylvania, and Lincoln University. Many shared the experience of being preachers’ kids.

Some of the standout contributors included noted artist Allan Randall Freelon, the first Black person to join the Philadelphia Print Club, who designed the cover for the first three issues. Freelon edited Black Opals alongside Bright, an early member of Delta Sigma Theta. Another founding editor was writer, educator, and folklorist Arthur Huff Fauset, whose sister, author Jessie Redmon Fauset, also contributed. Readers could find the work of Mae Cowdery, a prizewinning poet who was a senior at Girls’ High when Black Opals launched, not to mention a mentee of Locke’s and friend of Lincoln University alum Langston Hughes’ — both luminaries who wrote for Black Opals’ first issue as well.

“Philadelphia is the shrine of the Old Negro,” Locke began his essay “Hail Philadelphia. “More even than in Charleston or New Orleans, Baltimore or Boston, what there is of a tradition of breeding and respectability in the race lingers in the old Negro families of the city that was Tory before it was Quaker.”

Later, Locke added, celebrating the dawn of a new day: “But I hope Philadelphia youth will realize that the past can enslave more than the oppressor, and pride shackle stronger than prejudice… Greetings to those of you who are daring new things.”

Some of the writing in Black Opals is better than others. Perhaps the editors anticipated this, as the inside back cover reads: “Black Opals does not purport to be an aggregation of masters and masterpieces.”

The note continued, “These expressions, with the exceptions of contributions by recognized New Negro artists, are the embryonic outpourings of aspiring young Negroes living for the most part in Philadelphia. Their message is one of determination, hope, and we trust power.”

The exact reasons why the journal ceased publication after four issues remain undefined. Cofounder Arthur Huff Fauset told Jubilee in 1977, “If there had been a place to meet, we could have had a permanent group.” Jubilee suggested that a lack of audience was also a factor.

Goodman traces the recent uptick in the magazine’s popularity to times we’re living through, but also to the work of Chronicling Resistance, a project run by the Free Library and Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries, which highlighted Black Opals several years ago.

“It’ll be interesting to see if in 10 years, that’s still the case, or whether it’s part of the sort of cultural moment,” Goodman says.

Yolanda Wisher, who was Philadelphia’s third poet laureate, is hoping more people will continue to learn about Black Opals and its historically overlooked collective of writers.

“I think about this kind of in the way that I think about what might happen in the future to all the work that I do,” Wisher said, “Or all the work that I know people are doing here in Philly. It’s like, what if you don’t win a Pulitzer or a Nobel Prize, or somehow don’t have a building named after you? Will anybody know that you did what you did?”

Wisher, the author of Monk Eats an Afro, first read Black Opals in the late 2000s while conducting research on Black Philadelphia poets. She’s been hoping to bring back Black Opals for years, an idea that’s stayed with her since throwing an event in tribute to Black Opals at The Rosenbach in 2017 with fellow artists.

“There should be like a tour. There should be a textbook. People should be teaching this in their classes in Philadelphia schools,” Wisher stated. “We need to be hearing the story of young people writing, creating their own outlets for publication. And elders supporting that. Yeah, why couldn’t there be another Black Opals collective again?”