‘Burned’ by Edward Humes: Out of the ashes, the dirty secrets of forensic science

Fingerprinting, hair, fiber, and footprint matching, bite-mark comparisons, and ballistics -- all stock in trade for crime scene investigation -- are, the author claims, “tainted by systematic error, false assumptions and theories that turn out to never have been scientifically tested.”

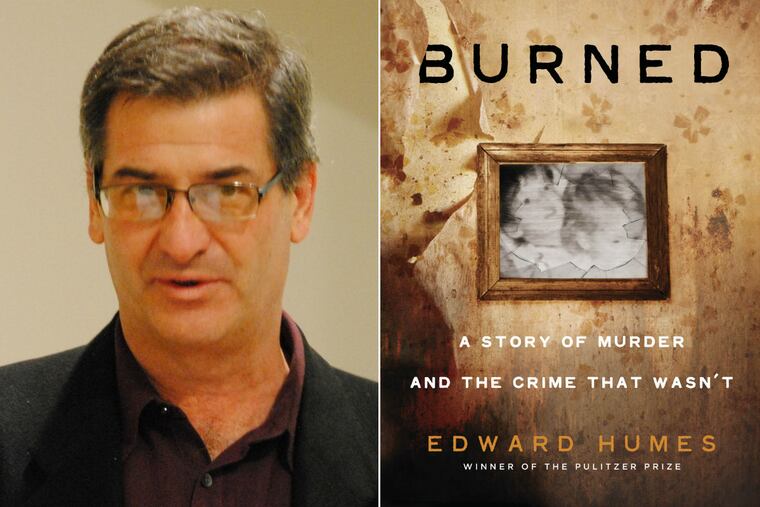

Burned

A True Story of Murder and the Crime That Wasn’t

By Edward Humes

Dutton. 320 pp. $28.

Reviewed by Glenn C. Altschuler

“If I am wrong,” declared Ron Ablott, the investigator of an apartment fire in a suburb of Los Angeles in which three young children perished, “then everything I have been taught and those people that have been taught before me, would all be wrong.”

Based on his testimony and the conclusions of other forensic scientists, Jo Ann Parks, the mother of the children, was convicted of arson and murder in 1992 and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

In Burned, journalist Edward Humes, author, among other books, of No Matter How Loud I Shout, provides a graphic and gripping account of the Parks case and the efforts of lawyers in the California Innocence Project to overturn Parks' conviction. Her prosecution, Humes maintains, was the outcome of a reliance on forensic experts whose claims to certainty, “built on the evidence of ash and char” and an ability “to read burn patterns like an ordinary person reads words on a page,” have now been challenged as the products of false assumptions, junk science, and cognitive “expectation biases" (based on the behavior of potential suspects).

Fires, Humes indicates, are difficult to investigate because they often consume physical evidence. Since Parks was convicted, he adds, the National Fire Protection Association and a commission appointed by President Barack Obama have identified a laundry list of “arson myths.” Not only did it discredit an age-old principle called “negative corpus” — which holds that the absence of evidence of an accident is relevant to a finding that a crime has been committed — it also pointed out that the recent forensic “revolution,” which has rethought or reapplied many of the central tenets of previous forensic practice, has resulted in a sharp decline in the number of fires deemed to be arson. Nonetheless, Humes writes, law enforcement officials have been reluctant to reopen old cases or release convicts from prison.

Humes also asserts that many forensic techniques unrelated to the Parks case, including fingerprinting; hair, fiber, and footprint matching; bite-mark comparisons; and ballistics are “tainted by systematic error, false assumptions and theories that turn out to never have been scientifically tested.” These “dirty secrets,” he believes, “have left the justice system alternately in a quiet panic, or in massive denial over the implications of the vanishing aura of CSI infallibility.”

Burned leaves us in suspense. After a habeas corpus hearing in 2017-18, Parks waits behind bars for a ruling on whether she should have a new trial. Humes’ readers are likely to be uncertain as well. How, they will wonder, will courts adjust to data demonstrating that one out of every four people who were wrongfully convicted and then later exonerated of murder or other serious felonies between 1989 and 2018 was a victim of false or misleading forensic evidence?

Glenn C. Altschuler is the Thomas and Dorothy Litwin Professor of American Studies at Cornell University.