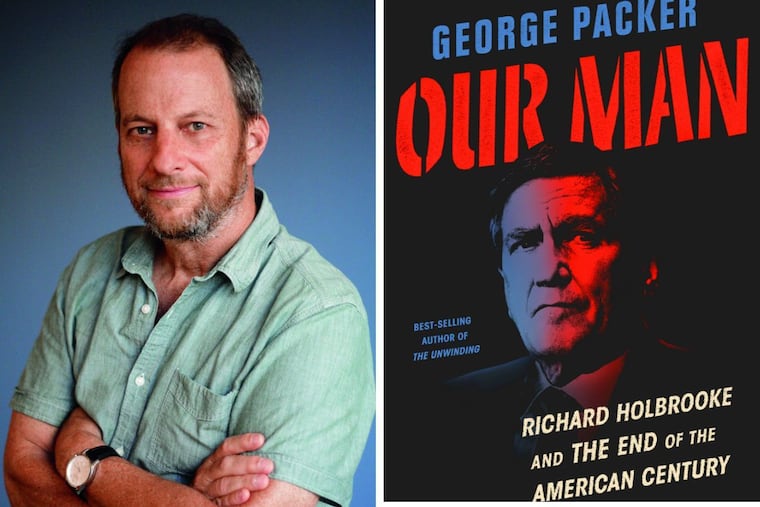

‘Our Man’ by George Packer: The toxic American tragedy of Richard Holbrooke

This is a big, richly detailed biography meant for a great man, but George Packer argues that Holbrooke's defects kept him from true greatness. Although Packer courageously details Holbrooke's demerits, he also engages in near-hero-worship of this strange, accomplished, self-destructive man.

Our Man

Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century

By George Packer

Knopf. 608 pp. $30

Reviewed by Adam B. Kushner

Richard Holbrooke was a rare creature — a figure from Greek tragedy contained within America’s foreign policy bureaucracy. The late diplomat possessed heroic talents and achieved feats of strength and rose high. But his own flaws undid him.

George Packer tells this parable in his strange new biography, Our Man: Richard Holbrooke and the End of the American Century. In some ways, the author hero-worships the world-bestriding personality who at times bent huge forces to his will.

Packer exhorts us not to judge Holbrooke for his litany of sins. “If, while following him, you ever feel a cluck rise to your palate, as I sometimes do,” he writes, “don’t forget that inside most people you read about in history books is a child who fiercely resisted toilet training. Suppose the mess they leave is inseparable from their reach and grasp? Then our judgment depends on what they’re ambitious for — the saving glimmer of wanting something worthy.” Hate the artist, love the art.

Yet, to his enormous credit, Packer then dwells on those sins, equipping us to condemn Holbrooke if we so desire. (And I do. I must.) Holbrooke "was an absent husband and an indifferent father." He cheated frequently over his three marriages and propositioned his best friend’s wife. Inside government, he fought constantly for status and recognition, leaked (and lied about it) to hurt rivals, kowtowed to bosses, terrorized subordinates, and elbowed his way into meetings where he wasn’t needed or wanted. "He is the most viperous character I know around this town," Henry Kissinger, the greatest operator of them all, once said of Holbrooke.

Packer believes one needn’t be good to do good things, and he is openly romantic about it. “The phrase 'great man’ now sounds anachronistic,” he writes, “but as an inspiration for human striving maybe we shouldn’t throw out the whole idea.”

And, sure, let’s give Holbrooke his due: He apprehended the folly of Vietnam at an absurdly early date. (“He believed that he knew more than any American official in Vietnam,” Packer writes. Perhaps he did.) He “was the first American official to denounce the crimes of the Khmer Rouge,” though it didn’t change U.S. policy. When Serbs and Croats and Bosnians began killing each other in the early ’90s, Holbrooke was among the first to agitate for intervention — a policy that eventually saved tens of thousands of lives. He was “brilliant and curious and widely read,” Packer kvells in one ovation, but he was also “unafraid to face the truth, cared enough to act on it, and was willing to take the consequences.”

This is a plausible position, maybe. Egotism and idealism "need each other to do any good. Idealism without egotism is feckless; egotism without idealism is destructive," Packer argues, riffing on Conrad. "Sometimes the two instincts got out of whack." But they combined beautifully when President Bill Clinton sent Holbrooke to end the Bosnian war, a task at which nobody else could have succeeded. He did it all by cajoling, drinking with, shouting at, and threatening all parties involved. The result was the Dayton Accords. Holbrooke’s name became a Serbian verb: holbrukciti, "to get your way through brute force."

Packer — the author of several other books, including The Unwinding, a National Book Award-winning tale of American decay — is a pleasant guide with a conversational tone. But writers are supposed to show, not tell. Packer tells us constantly how great Holbrooke was. But, redeemingly, he also shows Holbrooke’s ugliness. It is everywhere, and it’s revolting. If that was an authorial choice, it was a brave and intellectually honest one.

The real reckoning finally landed during the Obama years, when Holbrooke began jockeying for a position during the transition — and instantly alienated President Barack Obama. Hillary Clinton helped Holbrooke become the Af-Pak envoy, but eventually he torpedoed Washington’s relationship with Kabul. He recruited candidates to run against the corrupt president, Hamid Karzai, who found out, won reelection, and never again accepted Holbrooke as an interlocutor. The diplomat had the courageous and ultimately correct idea to begin talking to the Taliban — they would have to be part of any peace deal — but he had heart trouble and was suffering physically. He died in office, trying to get the negotiations started.

This is the kind of biography (massive, detailed) by the kind of author (respected, experienced) reserved for great books on great men. Packer doesn’t show that Holbrooke’s life is an allegory for the “end of the American century” — the title oversells — but he does make a case for Holbrooke’s place in the pantheon, showing that there was real idealism and skill buried beneath the layers of self-regard.

But his toxic, bridge-burning path kept him from the highest summit. “If you cut out the destructive element, you would kill the thing that made him almost great," Packer argues. I disagree. The real tragedy of greatness is the myth that it turns decency and efficacy into enemies.

Adam B. Kushner is the editor of the Outlook section at the Washington Post.