‘Late Migrations’ by Margaret Renkl: Nature, family, praise, in a book made of summer

In this lovely little book, the author interlaces brief, vivid celebrations of the natural world with stories of her family and upbringing in Alabama. She finds the whole world holy and is moved to praise at every turn.

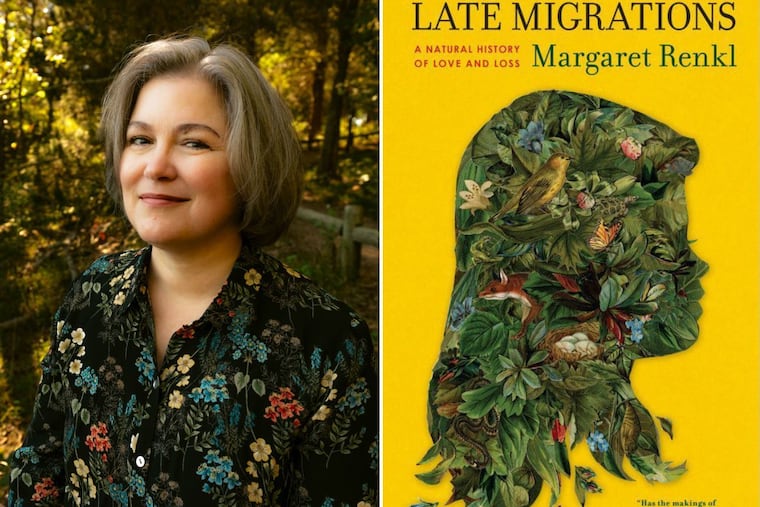

Late Migrations

A Natural History of Love and Loss

By Margaret Renkl

Milkweed Editions. 248 pp. $24

Reviewed by John Timpane

So you’re lounging at the lake, or the beach, or just on the porch, and you’ve stacked your summer reading high — your shoot-’em-up, say, your romance, or your big, fat historical novel or novelistic history. Great, totally great.

But, someplace there, make sure to slip in this exquisite little book. Because it may be the book of the summer.

Margaret Renkl’s Late Migration reads as if made of summer. Short chapters about the natural world interlace with a family story of birth, learning, tragedy, and love set in all seasons. But no matter the actual season, every chapter rustles with tremulous, climactic summer fullness.

Several of the chapters in Late Migrations have appeared in Renkl’s weekly New York Times column. Like nothing else in the newspaper, they burst with awareness of the things of nature, awareness that our lives are led in that midst, permeated with and part of the natural world. All is written with an open, joyful, yet steady voice of wonder. As she explains in “Gall”:

I grew up playing in the woods, and all my life I’ve turned to woodland paths when the world is too much with me, but I am no scientist. It took a lot of nerve for someone so ignorant of true wilderness to fashion herself as a nature writer, but the flip side of ignorance is astonishment, and I am good at astonishment.

That’s as good a self-explanation as any writer could give us. She may not know the science (although she knows the names of birds and plants with precision) but she knows the glory. That’s what poets do: They enact the impact of the real on our open minds and call on us to share the wonder. In “Migrants,” rose-breasted grosbeaks, in mid-migration from Central America to Canada, stop by:

I am not myself a serious birder, but I still feel a thrill when I notice a new face at the feeder, a stranger at the birdbath. I treasure these glimpses of the exotic, this sense of having traveled to distant lands, and hearing, however briefly, their strange, foreign songs.

Renkl sows in stories of her Alabama family that are sometimes homey, sometimes sad, sometimes studded with lunacy or violence. One star of the show is Renkl’s grandmother. Transcriptions of taped interviews let us hear her reminisce about a beloved dog (“She had crawled right up under the school building, right under where I sat. That’s where she was when she died.”), or the day her husband died, or author Renkl was born, or she herself was shot in an incident at a general store.

Renkl tells us of the moment she first realized she could read, the night she saw a meteor shower in Colorado, her miserable time at Penn and flight back home (she went on to earn degrees at Auburn and South Carolina State). “In the Storm, Safe from the Storm” brings us to Alabama, 1965, during a summer shower at night. Her father sits in the doorway of the house and sits her in his lap, to feel the cool wind. She lets the rain wet her toes, but her father encloses her in his coat: “I lean into him. I feel the heat from his body and the cool rain from the world, both at once.”

She builds a family, grieves at her empty nest when the kids leave for college, and grieves further when loss comes, as it must to anyone who lives at all in this world. “This talk of making peace with it,” she writes in “After the Fall,” “Of feeling it and then finding a way through. Of closure. It’s all nonsense.” What she does find is that “you are the old, ungrieving you and the new, ruined you. You are both, and you will always be both.” And then: “There is nothing to fear. There is nothing at all to fear. Walk out into the springtime … ”

The book, although it covers many emotions, owns the hush of high summer. In “Redbird, Sundown,” the bird is a “tiny god, all fiery light leading to him and gathered in him, lord of the sunset, this greeter of the coming dark.” Such reverence, such under- and overtones of prayer and praise. Several titles play with themes from the holy books (“He Is Not Here,” for example), with beatitudes and faith. The last essay is titled “Holy Holy Holy,” and the closing quote from Derek Walcott is “So much to do still, all of it praise.”

Renkl has been public about her struggles with her Catholic faith, the partings, the return. As a practicing Catholic, I can relate. But Margaret Renkl is the most sensible of spiritual writers. She’s not going to fool herself about the world. Late Migration sings, nevertheless, the best praise we can offer, praise that need not be pinned down to any single doctrine or teaching. She finds the whole world holy and is moved to praise at every turn. That’s enough to warm a lifetime of summers.