A New Orleans family history: Big promises, dashed hopes and rising water | Book review

The memoir is a delightful, deft, familiar — and ambitious — foray into family dynamics and working-class gusto, a relatable story of the townies in a city overrun by, and dependent upon, tourists.

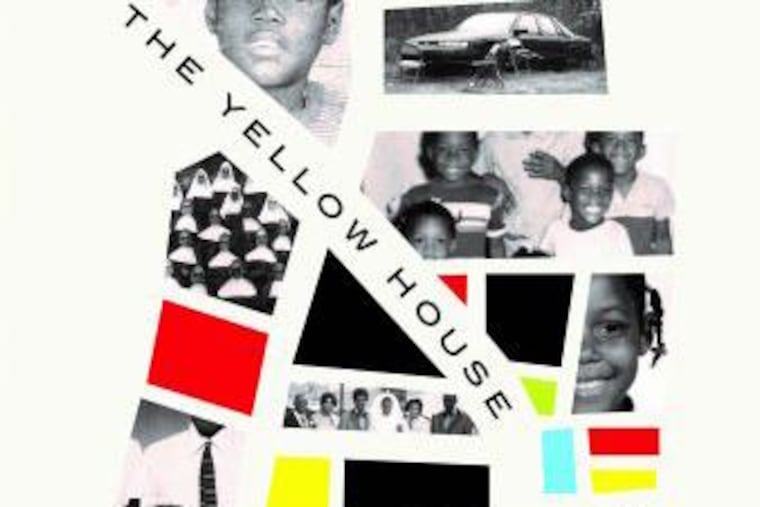

The Yellow House: A Memoir

By Sarah M. Broom

Grove. 376 pp. $26

Reviewed by Petula Dvorak

There is a New Orleans without Mardi Gras beads, without gators or gumbo. It’s a place far from Bourbon Street and without a hint of voodoo.

It's a place I knew well when I lived in the city. And that's not a good thing. I was a crime reporter at the time, not a person you wanted in your neighborhood.

Sarah M. Broom’s stirring memoir, The Yellow House, is set in this New Orleans. It’s New Orleans East, a part of the city that tourists, poets and drawling Big Easy narratives don’t visit. It’s the place where the creators of the magic — cooks, bellhops, maintenance crews — live their lives.

Broom describes it on a bus ride home: “All of us who had traveled to the French Quarter for work from elsewhere wore the day’s labor on our bodies. We could place each other instantly by our uniforms: Napoleon House workers wore all black with white lettering on the breast pocket. ... If you wore the grass-green outfit, the ugliest of them all, you worked at the Monteleone Hotel.”

The memoir is a delightful, deft, familiar — and ambitious — foray into family dynamics and working-class gusto, a relatable story of the townies in a city overrun by, and dependent upon, tourists.

The yellow house is the Broom family’s home in New Orleans East. It is their pride, hope and prison, guiding readers through the struggles of a black, working-class family. When Hurricane Katrina shatters their lives and scatters the family across the country, the book becomes far more urgent — and, I would argue, crucial. The yellow house is gutted by the issues confronting us today: pernicious racism, corporate greed, displacement, and the improbable arithmetic of survival as a member of the working poor.

Broom is the youngest of a 12-child, blended family. Accordingly, she begins with her own archaeological expedition into all the funny and poignant family history she missed, being the “babiest” of the bunch. She is a griot telling the story of an American black family, embroidering the family tree with sharp reportage that explains nicknames, courtships, awkward studio portraits, family lore, and the cruel everydayness of the era’s segregation.

Broom’s mother, Ivory Mae, said she and her siblings were raised by a hard-working mother who tried to shield them from racism. “But Joseph, Elaine and Ivory had only to walk to the curb outside their Roman Street house to see Taylor Park and its sign: NO N—, NO CHINESE AND NO DOGS. It was a strange sight, the mostly empty, fenced-in park in a black neighborhood.”

The (not always yellow) house appears in the story after Ivory Mae loses her first husband, who was killed by a hit-and-run driver while walking on the road outside Fort Hood, Texas, not long after he enlisted in the Army, a “black man run over while walking home, no explanation whatsoever, no fuss, no arrests,” Broom writes.

But the young father of two left a legacy: a life insurance policy. And that helped Ivory Mae buy the yellow house for $3,200 when she was just 19, becoming the first person in her immediate family to own a house. They were one of the only black families to move into a real estate experiment called New Orleans East, built atop a vast cypress swamp with ground too soft to support three people standing on it and — it would turn out — too soft to support the hubris of the Texas investors who built on it.

The Texans drained the swamp and erected a city of the future atop soggy land bounded by Lake Pontchartrain, the Mississippi River, Lake Borgne and the notorious Industrial Canal. Developers touted a space-age playground with shopping malls and an ice rink for the employees of the growing oil and gas industry and a nearby NASA facility. A New York Times article marveled at the vision: “City within a city rising in the South.”

Ivory Mae married again, to the author’s father, Simon Broom, one of the NASA workers. He brought more children and verve and merriment to the yellow house, fixing it with slapdash and good-enough husbandry and filling it with parties and music and laughter.

In 1965, Hurricane Betsy arrived.

“I was a tiny boy,” her brother Michael remembered. “Water was so high. I’m swimming, I’m swimming. The dogs, too. The water was moving through here like we was in a river.”

"Hundreds marooned on roofs as swollen waters rip levee. Hurricane Betsy leaves New Orleans with 16-foot flood," said the front page of the Chicago Tribune.

Sound familiar?

The Broom family recovered, but the rest of New Orleans East didn't. The investors didn't make good on their vision, and the folks who could afford to leave did. The Brooms stayed, Simon Broom died, and the family struggled to keep the ailing house together while the neighborhood decayed around them.

Broom watched New Orleans East collapse on itself and her neighbors move away one after another; it was about this time that my job kept bringing me down Chef Menteur Highway. Parking lots were where you got robbed, residential streets were where johns got laid.

Broom was too embarrassed to bring friends over. “Prostitution on Chef Menteur Highway seemed the only industry still booming, not a downturn in sight,” she writes.

She fled to college, moved to New York and had a dream job working for O Magazine. Then Katrina struck, and the legacy of New Orleans' struggles sucked her back in.

The yellow house twisted and broke in two. The family scattered to Texas, Mississippi, Alabama, Arizona, and California. New Orleanians didn’t usually leave New Orleans. In 2000, the city had the highest concentration — 77% — of residents who stayed where they were born. That changed with Katrina, which drained half the city’s population.

Three years after the storm, which she called “the Water,” Broom returned to New Orleans to work in the mayor’s office and write the story of this great city’s recovery. She quit after six months and explains the debacle with refreshing honesty.

It reads like real-life reporting from a Kafka book, an absurd world where paperwork is perpetually deemed incomplete, then lost again and again, and where a home is demolished after only one notice is sent to the broken, empty house.

“More and more I began to feel that I was on the wrong side of the fence, selling a recovery that wasn’t exactly happening for real people,” she writes, and confesses to what she thought of the mayor’s Road Home recovery program she was hired to tout. “Road to nowhere, I had taken to calling it.”

When she left the office to find stories of recovery to add to Mayor Ray Nagin’s speeches, she came up short. “Apartment complexes everywhere were still in ruins. It looked like the day after the Water, minus the flooding.”

And for those who had returned, “basic services such as trash pickup and water drainage were still scarce. Mounds of debris remained,” she writes.

Broom’s work here is an investigative reporter’s shaming story — from the profiteers who lured families to New Orleans East, to the failed Road Home recovery program that actually thwarted most residents’ returns — of our era’s messed-up priorities.

And we are left with the poignant vigil one of her brothers keeps over the plot of land where the yellow house once stood. He mows it weekly, tending to the fading memory of a home, when there is no home to return to.