Sonia Purnell’s ‘Woman of No Importance’: An American woman with disabilities who became a ‘dangerous’ wartime spy

She was a woman with a disability, and the United States was not even in World War Two yet. But Virginia Hall joined the Allied espionage effort, beginning a long career in which she would have to contend with male resistance.

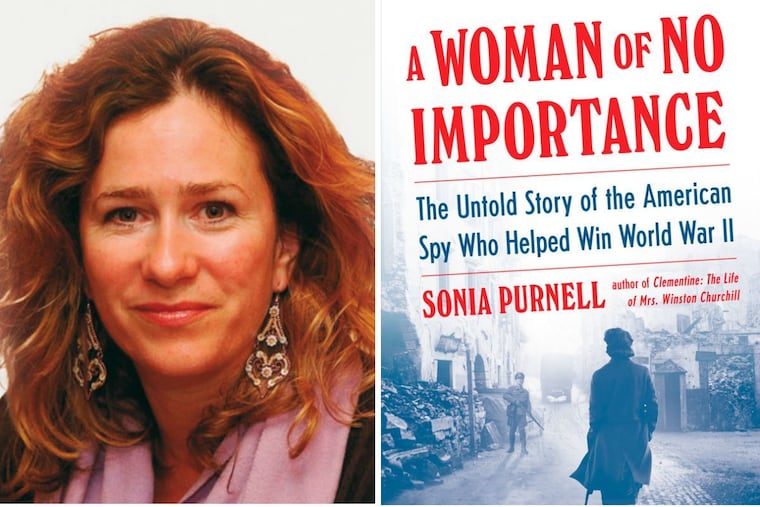

While writing Clementine: The Life of Mrs. Winston Churchill in 2015, and learning of the role intelligence played during World War II, journalist Sonia Purnell discovered Virginia Hall’s story and knew she had found her next book project. Purnell was fascinated by what motivated Hall, a disabled American woman who became one of the most dangerous Allied spies, to take insane gambles with her life when her country wasn’t even yet in the war.

This month, Purnell’s biography of Hall, A Woman of No Importance, is being published after years of research in three countries. She is doing a talk, answering questions, and signing books at the Union League on April 8. Purnell talked to us about why she feels Hall’s story is more timely than ever, how Hall faced the same struggles women today face in workplaces, and how she faced the epic task of declassifying U.K. intelligence documents in her research process.

In the prologue of the book, you write that we need Virginia Hall’s story of devotion to preserving people’s freedoms more than ever these days. Can you elaborate on that?

Any of us can see that the world is going through a period of turmoil. The idea that you can worship as you please, dress as you please, work as you please — all that is under threat. These themes looked different in the 1930s and 1940s, but certainly, erosion was happening in the same way. People were fearful that the freedoms they took for granted were under threat. And they were right. Virginia was there watching democracy come under attack. She saw the rise of fascism and felt powerfully about it. She wanted to do something because she came up in a time when women could vote, work, and do a lot of things for the first time. She realized that all those advances were in peril. Virginia wanted to get involved.

You encountered shoddy record-keeping that left gaps in Hall’s story. How did you bridge those gaps?

I was very fortunate to be able to track down the memories, letters, and diaries of various people who fought alongside her. Several of them wrote down personal recollections of her. Virginia’s niece Lorna was also able to flesh out the stories for me. For example, Virginia had told her that the crossing of the Pyrenees was the worst part of the war for her. I was also very lucky to access official documents in the U.K., France, and the U.S. Some are still classified in the U.K. A former intelligence officer helped me declassify a few of them, but this was basically three years of detective work. It was a huge, epic task.

Did you find anything surprising about Hall?

Definitely how kind she could be. Life had not been kind to her, but she had a very tender side to her. She was incredibly compassionate. She didn’t forget her friends. Considering everything that had happened to her, that’s pretty remarkable.

Was there a part of her story that affected you emotionally more than others?

The end of her career — being mismanaged by the OSS — was so sad. The CIA realizes now that they didn’t employ her properly and that they wasted her talent. I feel low about that. But what makes me happy is that she did have Paul [Goillot, a former agent whom she married in 1950]. She did finally find someone who understood her. He lightened her life because he was fun, engaging, and a bit mischievous. Perhaps because he was around, the CIA thing was something she could bear.

So much of what happened to Virginia happens today. Women find themselves to be underrated. When she went out into France, she was in a very junior role. She made that into so much more while not being recognized. She battled with her male co-workers — that’s really familiar to women today.

If you could go back in time and meet Virginia, is there anything you would like to ask her?

I’d just ask her for advice. I’d say, “Where did you find it in yourself to be that brave? And what were you saying to yourself when you went back into the field disguised as a peasant woman? Where did you find that resourcefulness and that calm, and can I have a bit of it, please?” [Laughs.] Virginia was a Resistance hero. She did things that women weren’t expected to do and showed how they could be done. And as one of her managers said, she was “almost embarrassingly successful.”

AUTHOR APPEARANCE

Sonia Purnell, ‘A Woman of No Importance’

6:30 p.m., April 8, Union League of Philadelphia, 140 S. Broad St. Tickets: $30 Union League members, $40 non-members; reception, lecture, and dinner $90 members and non-members. Information: Tickets available at royal-oak.org/events/2019-spring-philadelphia-a-woman-of-no-importance.