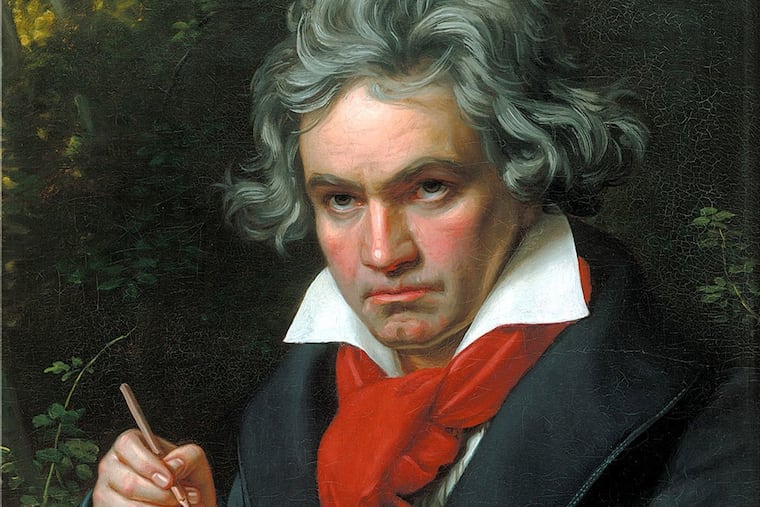

Why Beethoven is so relatable right now (and it’s not just because his hair is a wreck)

His music is unvarnished, unfiltered, elemental — and suited to the raw place our emotions are at right now. Is it any wonder millions are streaming Beethoven?

With barbershops and hair salons shuttered, many of us are starting to look as scruffy as middle-aged Beethoven. But that’s not why so many roads now lead to Beethoven’s music as we wait in our homes for the pandemic to be over.

“There’s strong connection [with] what is happening to us,” said pianist Maria Joao Pires as she introduced Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No 8, Op. 13, (“Pathetique”) on a March 28 #WorldPianoDay webcast. “Through him, we can learn many important things for our present and future.”

Then, she launched into the sonata’s suffocating C-minor darkness, where the composer rages against seemingly intractable limitations.

Beethoven was in the air to begin with: His 250th birthday year had complete cycles of symphonies, sonatas, and string quartets scheduled far and wide — now mostly canceled.

The COVID-19 virus has also hit the classical music community directly: Conductor Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla and tenor Placido Domingo are just two to test positive.

But does that explain why the Philadelphia Orchestra’s BeethovenNOW concert, with two full symphonies webcast from an empty Verizon Hall on March 12, is up to 771,000 YouTube views? Or why the Rotterdam Philharmonic’s abbreviated Beethoven 9th video — with each instrumentalist playing separately from home, titled From Us to You, is closing in on 2 million views since its March 20 posting?

Unvarnished emotion

No. Beethoven is far more than a commodity. His music is a state of mind.

The quarantine mentality emphasizes essentials (like staying in) over cosmetic priorities (like hair and makeup), which meshes well with his unvarnished, less-filtered, more elemental means of communication.

When the Philadelphia Orchestra played its audience-less Beethoven concert, I asked concertmaster David Kim what the effect might’ve been with a carefree program of Offenbach and Chabrier. “I think it would be just as meaningful,” he said. Classical music often takes the flavor of its surroundings.

» READ MORE: Coronavirus forced the Philadelphia Orchestra to play to an empty house. And I was there as a witness.

But among the hundreds of classical videos hitting the web with the world on lockdown, Beethoven makes a singular connection.

Fear is so much in the air, as soprano Angel Blue acknowledged last week on her do-it-herself Facebook talk show “Faithful Friday.” She and her virtual guest, soprano Christine Goerke, addressed the significant financial insecurity they face amid performance cancellations.

Musical escapism doesn’t cut it. When the Toronto Symphony followed in Rotterdam’s footsteps with Copland’s Appalachian Spring beaming in from the separate homes of its players, the usual feel-good moment when “Simple Gifts” arrives amid folksy harmonies felt oddly contrived.

Normally I love the piece. This time, Copland seemed to be selling me a bill of goods. Right now, any music with a strong decorative element seems irrelevant.

Chopin has been coming up a lot — not the bouncy mazurkas but the spooky nocturnes that feel like apprehensive journeys into the unknown, as played by Jan Lisiecki at #WorldPianoDay.

On the same March 28 webcast, Dutch composer Joep Beving’s Solitude, written in recent days as a reaction to the pandemic, had a remarkably similar manner, as did a performance of a simple Orlando Gibbons hymn from Shakespeare’s era sung by a choir that was spread out inside St. Mary’s Church in London according to social distancing protocol.

Such is the directness that you consistently hear from Beethoven, whose place in society was that of an exalted celebrity and also a perpetual outsider, isolated by his gruff temperament and later by his deafness.

Before Beethoven, composers were employees vying tirelessly for church jobs (J.S. Bach) and court appointments (Mozart), and were obliged to write the kind of music that would suit those circles. But after his early career as a piano virtuoso in 19th-century Vienna, Beethoven was a free-agent composer with no obligation to any circles.

Music outside of time

His chamber music outstripped the abilities of amateurs. Pianos could barely take the beating of his high-density sonatas. Thus, he lived outside his time — which meant there are fewer barriers for him to occupy our time.

Bach, Mozart, and Schubert all reached similar places of freedom in their creative lives, but Beethoven got there early on — and constantly looked beyond the surface to what’s really happening.

In his opera Fidelio, the bare-bones plot about a woman rescuing her political prisoner husband encompasses so many issues that you’re going to encounter something that you’ve been recently thinking about. In a March 28 webcast by London’s Royal Opera, I seized upon the blind hope of the title character, plus the chorus of prisoners who are momentarily let out into the daylight before re-incarceration.

If I’m hearing the music differently, chances are high that the performers are rethinking the notes they’re playing in the face of the pandemic.

I’ve heard numerous instances of that over the past two weeks, most dramatically in Jonathan Biss’ March 26 recital of the composer’s last three piano sonatas — an event that, in Beethovian fashion, moved forward against all odds.

The webcast was planned to be from New York’s 92nd Street Y. Then Biss couldn’t get there from Philadelphia, and the New York camera crew couldn’t get to him.

So Biss set up an iPhone and tripod in his Philadelphia apartment himself, but opted to prerecord it because he didn’t trust the local WiFi and didn’t want to disturb his neighbors.

That last concern was well-founded. The sonatas themselves represent one of Beethoven’s pianistic summits. “He was a person of infinite imagination and infinite ideals. … And shuttered off from the rest of the world, those qualities blossomed into something even more extraordinary,” said Biss, by way of introduction.

His performance wasn’t that of Beethoven the spiritual prophet but Beethoven the fighter. Tempos bordered on frenetic. Music that always sounds packed with more notes than a nanosecond can hold seemed even more compact, almost defying laws of musical physics.

Edges were jagged. Notes were missed. While Beethoven’s contours were respected, passages that were supposed to be soft were still tough, imposing, and full of momentum.

Of course, live performances are always different. Of course, artists are constantly evolving their interpretations of great music. But not like this.

Biss had become a different, newly minted pianist for our strange new world.

The message: Just because we’re confined doesn’t mean we’re restricted. And that’s every reason to resist the virus — tomorrow, tomorrow, and tomorrow.

“We’re both alive,” says King Henry II to Eleanor of Aquitaine in the film The Lion in the Winter, “and for all I know, that’s what hope is.”