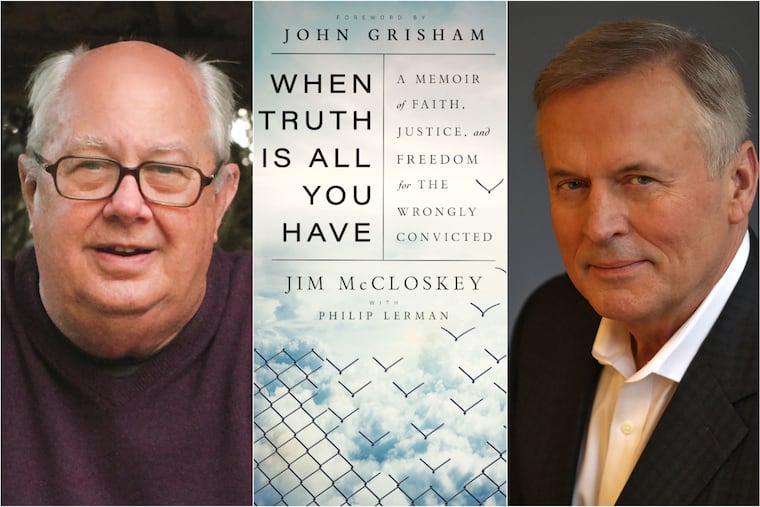

New Jersey’s own ‘Exonerator’ has helped set 63 people free. John Grisham is a fan of his new book.

In “When Truth Is All You Have,” the former businessman and Vietnam veteran recounts the religious awakening that put him on the path to the seminary, and the encounter with a New Jersey inmate that 40 years ago detoured him into a different form of ministry.

John Grisham and others call Jim McCloskey “The Exonerator.” For 40 years, starting before the use of DNA evidence gave rise to the Innocence Project, the Havertown native and founder of Princeton-based Centurion Ministries has been working to free wrongfully convicted men and women.

So far, 63 people, including four from Philadelphia, have walked out of prison with the help of the organization, from which he retired in 2015. (It’s now known as just Centurion and is headed by McCloskey’s longtime collaborator Kate Germond.)

McCloskey is a graduate of Princeton Theological Seminary and named Centurion for the Roman in the Gospel of Luke who said of the crucified Jesus, “Certainly, this man was innocent!”

When Truth Is All You Have: A Memoir of Faith, Justice, and Freedom for the Wrongly Convicted is his new book, being published Tuesday (Doubleday, $26.95). In it, the former businessman and Vietnam veteran recounts the religious awakening in his 30s that put him on the path to the seminary, and the encounter with a New Jersey inmate that detoured him into a different form of ministry.

McCloskey, who continues to work on a couple of cases, also paints a picture of a badly flawed justice system that produces more wrongful convictions than he thinks most people realize.

» READ MORE: Philadelphia man exonerated after 21 years in prison wins $6.25 million settlement

The book’s foreword is by Grisham, whose 2019 best-seller The Guardians includes a main character who was inspired by McCloskey. At 7:30 p.m. Thursday, McCloskey and Grisham will appear together in an event on Zoom sponsored by the Princeton Public Library. (Registration is at eventbrite.com.)

Speaking with The Inquirer last week, McCloskey talked about jailhouse “confessions,” how DNA-related exonerations are changing attitudes, and about what Grisham did and didn’t get right in his fictional version of Centurion. This interview has been edited and condensed.

What do you wish prospective jurors knew about how the justice system works?

False convictions, throughout the United States, [have] been going on for decades and decades. I don’t think the public has any idea how systemic the problem is.

When I started out in 1980, I was 37 years old. I had no experience with the criminal justice system in any form. And I always believed that the police and the prosecutors cared about one thing, and this sounds Sunday school-ish, but truth and justice, that they would never suborn perjury or do anything other than do their best to find the real perpetrator. I believe that most people — I’m talking about largely white people who have had no negative experiences with law enforcement — they believe that the police and the prosecutors are out to protect and serve. Whereas communities of color have a whole different view of that.

So I’m trying to hopefully educate the public about how this happens, and what to be on the lookout for.

Jailhouse “confessions,” in which the defendant is said to have proclaimed his guilt to another inmate, have been at the bottom of many of the cases you’ve investigated. Do we need a new standard for admitting them as evidence?

There have been calls to just completely eliminate jailhouse confessions. The ones who [testify to them] are mostly career criminals used by the prosecutors or the district attorneys to give what in my experience has been universally false testimony in exchange for, a lot of times, secret deals between the DA and the inmate wherein that person gets a sweet deal, mostly noncustodial time for his own crimes.

The way you fix it, in my view, is to eliminate such testimony. It’s almost universally bogus.

People in law enforcement have been complaining for years about the so-called “CSI” effect, which has juries expecting definitive forensic evidence. Yet in several of your cases, the wrongful conviction seems to have turned on an attempt to oversell the science — as when for instance, someone testified to the “age” of fingerprints. How are nonexperts supposed to sort this out?

They must not take it as gospel whatever the crime lab person in the local police department says. It might not be accurate, or might be exaggerated. So they have to be more careful of blindly accepting that kind of evidence.

Every person we’ve ever worked to free was indigent. In many instances, they have court-appointed attorneys who are inexperienced, and besides that they’re funded very little money to go out and hire their own forensic experts who could possibly rebut what the crime lab presents.

I’m probably one of the few people who can say that I’ve read your book, but not John Grisham’s “The Guardians,” which includes a character you reportedly inspired. Do you come off as more heroic in his telling? Because you seem to have gone to a lot of trouble to not paint yourself as a saint in your book.

[Laughs] You’re right. I’m no saint, and I wanted the readers to know that I don’t think of myself in those terms. And I think that’s quite evident in some of the accounts of my private life.

I can say that John Grisham, he gets its. He’s very knowledgeable about wrongful convictions, and he’s very familiar with our work. His telling of that story in The Guardians was, I’d say, 75% accurate of how we go about doing our work. I don’t know if I looked more heroic in his telling. But he does have that central character who apparently is modeled after me doing some things in The Guardians that I would never do [including stealing something from an evidence locker]. I would never dare attempt to steal any evidence. We would use proper channels to get that done.

He also has Guardian Ministries, the organization in the book, offering cash for some witnesses, which we won’t do because it could serve to impeach their credibility down the road.

» READ MORE: At 82, a just-released Graterford prisoner savors a taste of freedom

You write that DNA evidence has changed the criminal justice landscape, but when you began getting people exonerated, that wasn’t yet available. What’s the difference that it’s made?

In 1989 [the same year Gary Dotson became the first person in the U.S. to be exonerated of a crime through DNA evidence], a couple of law schools formed the National Registry of Exonerations. And they’ve documented the numbers: [More than] 2,600 men and women have been exonerated since then.

What DNA and all the other non-DNA exonerations have demonstrated to those who administer the criminal justice system is [what they didn’t know]. They had no idea that eyewitness testimony was as unreliable as it is. And had no idea that innocent people would falsely confess to crimes when they were arrested. So it really shed light on a number of factors that go into wrongful convictions and how unreliable that kind of evidence is. It has awakened an otherwise very complacent legal community.

» READ MORE: The case of Larry Walker

You argue in your book that the system doesn’t want to change, and that while there are good cops, the problems with police go beyond “a few bad apples.” Where do you stand on calls to defund the police?

My understanding of it is what people are calling for by “defund” is to take money out of the police budget and provide it to others, the state or local agencies who could better work with addiction and mental health problems. I don’t claim to be an expert. It might deserve some serious consideration.

Would it help prevent wrongful convictions?

Nobody really knows at this point. Will it affect concretely the homicide investigation department or the [sex crimes] investigation unit or [those investigating] crimes against people? I don’t know if it would affect the resources that police would have available to themselves to legitimately and thoroughly investigate those crimes.