Matisse’s caretaker, muse, and manager is a star of PMA exhibit

Matisse painted Lydia Delectorskaya while she managed his studio and cared for him in his final years. Witness her contributions at the ongoing PMA show.

Henri Matisse loved painting more than he loved his wife, and he told her that when they got married. He loved making pictures of women: colorful scenes of male-free paradise, swirling portraits in black ink, royal-blue bodies cut from sheets of collage paper.

Women also surrounded the outside of Matisse’s canvases, and even ran the show behind the scenes. Lydia Delectorskaya, a Russian émigré who worked her way from model to studio manager, is one of the many women who helped Matisse the man become Matisse the brand — the quiet but vibrant titan of 20th-century art.

She stars on both sides of the canvas in Philadelphia Museum of Art’s “Matisse in the 1930s,” on view through Jan. 29.

Matisse first supercharged the avant-garde in the early 1900s, lighting fireworks of pure pigment across canvases that were laughed off by critics. The Postimpressionists had severed canvas color from reality, but Matisse and his cohort pushed the experiment further. They would douse a whole canvas in red if red felt right, and they were called Fauves, or “wild beasts,” which also felt right.

As the Fauvist period fizzled out, in 1910, Delectorskaya was born in Russia. Orphaned at 12, she moved to France to study medicine but dropped out when she couldn’t afford tuition. She got by as a film extra, club dancer, and occasional artist model. When an aging and aching Matisse needed extra hands for a mural in 1931, the young Russian got the six-month gig as a studio assistant.

“Matisse in the 1930s” points to this mural, a project for Pennsylvania collector Albert Barnes, as a breakthrough for an inspiration-starved artist. Perhaps, but it had also been a disaster. The all-consuming commission imperiled Matisse’s marriage and exhausted his already ailing wife, Amélie. When he sailed back to the U.S. to install the mural in 1933, Barnes refused to show it to the public, to critics, or even to Matisse. The artist had a heart attack and returned to France in despair.

Meanwhile, Delectorskaya had been hired as a caretaker for Amélie. At 22, she also posed for a charcoal sketch for Matisse. Something clicked. For the next six years, she sat for almost every drawing and painting that Matisse made. She took the reins of Matisse Inc., managing his archive, working with dealers and gallerists, even naming some of his paintings.

The bond wasn’t romantic, insisted Delectorskaya, but something even deeper. The studio muse became the studio manager, a creative infidelity that Amélie couldn’t stomach. She left Matisse for good in 1939.

Matisse, almost 70, wanted someone young, tough, and hardy at his side. The color-drunk café lounger had become a homebody who worked and slept in his studio. And then there was the asthma, the arthritis, the anxiety, the insomnia. By decade’s end, he rarely even walked, confined first to a rocking chair, then a wheelchair, then the bed inside his studio.

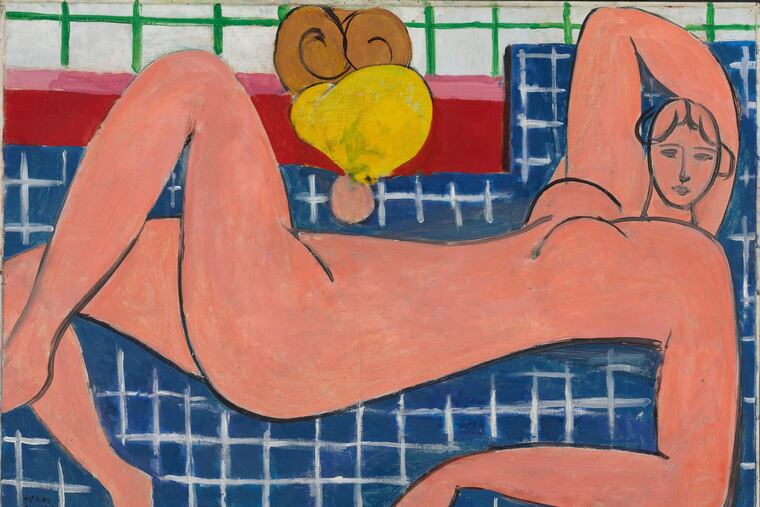

But still he managed to make art. The PMA show’s centerpiece, Large Reclining Nude from 1935, shows Delectorskaya drawn in patchy, eraser-pink oil paint. If it’s a masterpiece you’re after, linger here. This is a quintessential Matisse: a picture that works even though it shouldn’t. The torqued head is too small, the arms too big, the torso too long. Matisse can make a living thing out of anything, and out of nothing. He loves to give us just enough detail to see something whole, and not just whole but huge. It’s a 3-foot-long canvas, but it settles in your memory as something twice that size.

Nude phases

As a genre in Western art, the nude has baggage. For centuries, they had been painted by men for a mostly male audience. The man got to be the looker, the woman the object. Or as the critic John Berger put it: “Men act and women appear.” The Guerilla Girls put an exclamation point on that sentiment in 1989, asking why women had to be naked to be on the walls of a museum.

The PMA show nuances this attitude toward the nude. To the left of Large Reclining Nude, we see a grid of 22 photographs that document the phases the figure went through as Matisse reshaped his idea. Between each version, Delectorskaya wiped down the canvas with turpentine, inserting her hand into the image-making process. Here the model not only looks back at us, but she steps back and looks at the piece alongside us. She plays a part and takes part in the picture.

The canvas had been reserved for the American collector Etta Cone, whose unmatched Matisse collection lives in the Baltimore Museum of Art. On the West Coast, Sarah Stein (sister-in-law to Gertrude) had brought her mighty Matisse collection from Paris to San Francisco. These were, without a doubt, Matisse’s most important patrons. His pictures had been painted by a man, but so many of them had been painted for the enterprising eyes of women.

On your way toward the charming 1930s-themed gift shop, take a final look at Delectorskaya in a blue dress. Here she has sewn her own outfit. The curators have draped the original blue garment over a chair next to the canvas, another nod to her hand in coauthoring a canvas.

It’s a story for the screen: The orphaned refugee who worked her way from model to confidante, never a passive muse or studio serf. After his death, she left the household leaving the family to plan Matisse’s funeral. She wrote two books about him, assisted his biographers on their books, and worked with museum directors to establish his legacy. Matisse had been famous in life, but Lydia Delectorskaya helped secure his place in art history.

In 1949, as Delectorskaya and Matisse pioneered his giant cut-paper collages, Simone de Beauvoir seared the patriarchy with her blowtorch treatise on gender, The Second Sex. “Representation of the world, like the world itself,” she wrote, “is the work of men.” Women, confined to a secondary role, “dream through the dreams of men,” de Beauvoir added.

Those words still smolder. And yet, Delectorskaya’s life was spectacular. As she sat with Matisse on his deathbed, in 1954, he drew her portrait with a ballpoint pen on sheets of writing paper. It must have felt like living. One more vision of joy and light. Were those dreams not hers, too?

“Matisse in the 1930s” runs through Jan. 29 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. For details, visit: https://philamuseum.org/