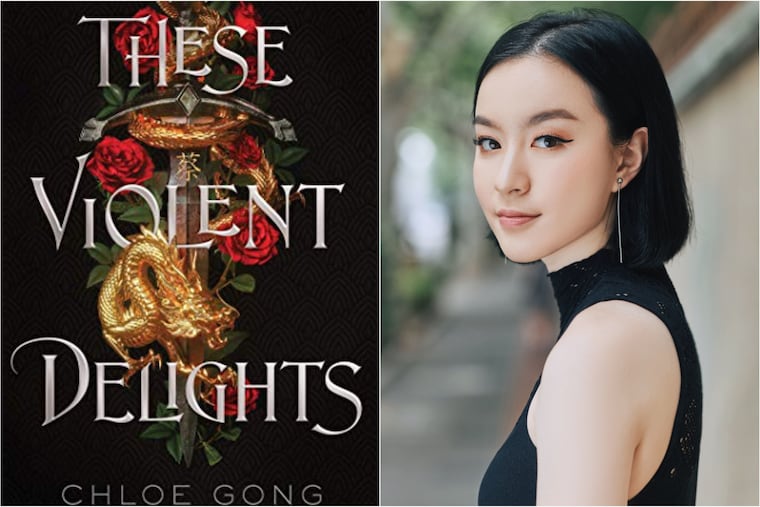

Penn senior Chloe Gong gets a ‘must-read’ Kirkus rating for her first novel, a cliff-hanging romance mystery

"These Violent Delights" is a Romeo-and-Juliet story set in 1920s Shanghai, with the now-former lovers cast as heirs to their respective crime families.

Chloe Gong’s debut novel, These Violent Delights is 464 pages of action, romance, and mystery that’s been hailed as “a must-read with a conclusion that will leave readers craving more." The more? That would be the second book in the University of Pennsylvania senior’s young-adult duology, which is due out next fall.

A Romeo-and-Juliet story set in 1920s Shanghai, These Violent Delights (Margaret K. McElderry Books, $19.99), which will be published Tuesday, casts its two now-former lovers, Juliette Cai and Roma Montagov, as heirs to their respective crime families, whose blood feud the pair must temporarily set aside to save the city from a monstrous contagion.

Gong, who first started uploading stories to the internet at 13, was born in Shanghai and raised in New Zealand. Her senior year at Penn, where she’s double-majoring in English and international relations, is on Zoom. Rather than remain home, she’s living off-campus in West Philadelphia because the time difference between Auckland and Philly — currently 18 hours — meant that "I would have had to like completely live nocturnally.”

In a recent interview, Gong talked about taking on one of Shakespeare’s most famous plays, the other heroines who inspired her, and how, at 21, she’s beginning, reluctantly, to age out of the young-adult fiction genre.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

When did you start writing this story? Because a plot line involving the fight to stem a swiftly moving contagion feels pretty timely.

I got the idea for this before starting college. New Zealand’s school calendar is from like February to December-ish. So I had actually graduated in December. Since I’d already made up my mind to come to the U.S. for college, I had from December to September essentially as a gap year. So it was during that time that I first got the idea for it. I didn’t actually write the book until after freshman year, because once I got into school, it just became so busy that I had to set it aside. So the contagion, and it actually being an epidemic, actually had come to form way before we ever knew that this was going to happen this year.

And you came here from New Zealand, which has had a pretty good handle on the pandemic.

Which is why when I said I was coming back, people were like, “Why would you do that?” Because New Zealand was COVID-free for like 100 days. We’ve got a few cases slipping in again, but otherwise, while the U.S. was in its most intense lockdown, everyone at home was going out to restaurants, it was like normal again.

What’s the appeal of riffing on a story that everyone knows, or thinks they know?

I wanted to do a story about a blood feud. People are going to say, “Oh, Romeo and Juliet,” because it’s such a touchstone text. You can’t get away from it. So my line of reasoning was, why not directly engage with it? And then take something that everyone knows, and then tell them, “Look, I’m reimagining it now in a different context.” I’m a huge Shakespeare fan, anyway.

Why did you choose 1920s Shanghai as the setting?

I had always been interested in the Roaring ’20s, which is funny, because now we’re entering the new ’20s and there are so many parallels now with 100 years ago, it’s actually insane. But I was always mystified by why we got the Roaring ’20s aesthetic without the politics side. There was so much racial tension going on in America and in places outside, there were global imperial efforts and colonial efforts.

I turned to Shanghai because I already had this familiarity with it because of the stories my parents have told me, the stories my relatives have told me, and just all the little things that you kind of pick up because you’re in the culture. The more I researched it, the more it seemed to fit the storyline.

Juliette is in many ways a very contemporary character. Would it be safe to say you didn’t feel completely constrained by your chosen time and place?

When I set out to write Juliette, I was very much inspired by the classic YA [young adult] heroines that I grew up reading. So like Katniss Everdeen [of The Hunger Games trilogy] and Beatrice Prior of Divergent and Celaena Sardothien of the Throne of Glass series. I wanted a YA heroine who was reminiscent of the stars of the shelves when I was reading. But then she’s also Asian, because that was what was lacking when I was growing up. I had all of these heroines who I loved and admired so much, but none of them looked like me.

At one point, Juliette’s father, Lord Cai, says to her, “The most dangerous people are the powerful white men who feel as if they’ve been slighted.” That also feels very much of the moment. Was that perspective always part of your story?

It’s always been like that. It almost feels like nothing’s changed, and yet so much has changed. Because I grew up in the Western world, my mother tongue is English. I’m not very literate in Chinese — I speak it fluently, because that’s what I speak at home, but I can’t read or write it past elementary school. So I couldn’t do any research in Chinese [without help from her parents]. I had to go to English resources, which meant I was actually looking at [1920s Shanghai] from the foreigners' angle. So it became so interesting to see the insidious kind of observations they were making, and the horrible way that they perceived the “savage” locals.

I very much came into [the book] with a down-with-colonialism kind of thing.

I lost count of the number of languages in which Juliette appears to be fluent. How many do you speak?

I speak English. And I badly speak Mandarin because I grew up speaking Shanghainese. I also took French through all of my high school years, and then through college as well. So I’m like OK at French, but that’s just three or four languages, counting the two [Chinese] dialects.

What makes “These Violent Delights” a YA novel, and not just a novel?

The publishing industry tends to define like YA [by] the ages of the main characters. And sometimes it’s about the content. So if there’s too much violence, they will try to categorize it as adult. But I think a YA book is written for teens in mind. When I wrote this, I wanted it to have the same role as the books that I grew up with. I knew that I wanted to reach teenagers who were looking for strong heroines, and to see themselves on the bookshelves.

One of your majors is English. What are you reading?

My English classes actually broaden my horizons a lot. They make me read a lot of adult books. I still don’t feel like an adult, so a lot of times the things I’ll be reading, it’ll be like, this is interesting as a story, but I’m not as invested in the story as I would be if it was young adult. I think that’s going to change because as I get older, I have started to feel like YA is less relevant. I’m feeling that switch, and I don’t like it, because it means I’m growing up.

This story has been corrected to reflect that Gong was born in Shanghai. An earlier version misidentified her birthplace.