Why Apple and other tech giants fight digital right-to-repair bills

Independent repair shops say they are frustrated by all the blocks that tech firms put in their way. Tech firms say the independent repairers could harm devices or expose them to hacks

WASHINGTON — Alex Buchon carefully inserted a slim, credit-card-sized tool into the gently warmed glue holding a broken iPad together. Patiently, he sliced through the glue to separate the screen from the rest of the device, exposing its innards.

The electronics technician needed to get inside to determine whether the device needed a new battery. If so, he wouldn’t be able to get it from Apple — the company makes them available only to Apple dealers and Apple-authorized repair shops. Instead, DMV Unlocked Wireless, the Washington, D.C., store that employs Buchon, stocks knockoffs and parts scrounged from discarded devices.

Independent repair shops and home tinkerers would have a much easier time if Apple provided them with parts, instructions and software. Legislation considered this year in 20 states would require manufacturers to do just that — but so far, the so-called right-to-repair measures have foundered against the fierce opposition of the tech industry.

The bills would apply to cellphones, tablets, farm equipment, appliances and any other products with software and computer chips. Some of the measures have been withdrawn, others are languishing in committees, and none has received a floor vote.

Lawmakers’ interest in the issue has grown since a few years ago, when only a handful of bills were introduced. But so has the opposition.

“We fully understand the desire of tinkerers, and do-it-yourselfers, to repair broken appliances and devices,” said Dusty Brighton, executive director of the Security Innovation Center, a coalition of tech companies that has opposed the measures. “[But] the electronics are highly integrated products, and repairs require training and accountability. Untrained repairs can compromise … safety, privacy and security.”

But Maureen Mahoney, a policy analyst for Consumers Union, said manufacturers are “conjuring up safety risks” to sway legislators.

She noted that car companies made some of the same arguments several years ago, before Massachusetts voters in 2012 approved the first automotive right-to-repair law.

“It’s hard to think of a product that has more to do with safety than automobiles, and we haven’t seen safety problems with that,” Mahoney said. “It should be up to the consumers to decide who repairs their products.”

Intense lobbying

New Hampshire State Rep. David Luneau, a Democrat, witnessed the vehemence of the opposition when his digital right-to-repair bill was considered in committee: Opponents wearing green and yellow John Deere T-shirts packed the hearing room. The farm equipment manufacturer opposes the bills because it fears its technology could be corrupted by amateur or untrained repairers.

“I look at it as a consumer protection bill,” Luneau said. “It provides the consumer with options on how to prolong the usefulness of equipment they buy. It takes away a little bit of industry control in terms of extending the life of a piece of equipment.”

John Deere responded to a Stateline inquiry, saying the firm “supports the right to repair but not the right to modify.” Customers can “maintain or repair” the product, but cannot have access to embedded software, which is designed to control emissions and safe operation.

The committee is set to vote on Luneau’s bill in a few weeks, but State Rep. John Hunt, the panel’s highest-ranking Republican, said it is unlikely to pass. The bill could force companies to give away proprietary information, said Hunt, a former Apple dealer.

John Reynolds, a technician at the Little Shop of Hardware, in Baltimore, explains the challenges of fixing computers without being able to order parts directly from the manufacturer.

“If New Hampshire were to pass this, do you think Apple would roll over and make this available?" he said. "No. They would say they are not selling iPhones or computers in New Hampshire.”

Apple representatives did not respond to multiple requests for comment. However, the company announced in August that if independent technicians nationwide take the company’s certification course, it will provide them with genuine parts and equipment to repair iPhones.

In California, home to Silicon Valley, a proposed right-to-repair measure also has run into stiff headwinds. A hearing on the bill scheduled for this summer was postponed after tech companies raised strong objections, making it unlikely that the full legislature will act on it this year.

Nathan Proctor, campaign director for U.S. Public Interest Research Group, which supports the right-to-repair bill, said California could be a bellwether because it is the leading high-tech state and much of the tech media is based there.

Lower prices

Fraz Khalid, who owns DMV Unlocked Wireless, said third-party suppliers usually catch up to new phones and parts within a month of their introduction by the manufacturers, and, he said, they are the same quality as genuine parts. “Everybody makes something,” he smiles, even the special screwdriver needed to open the iPhone 10.

Khalid said the problem with becoming an Apple-certified repairer is that it prohibits you from doing repairs on other kinds of phones. In addition, he said, his shop can perform repairs for about a third of the cost of a certified Apple repair. A screen repair for an out-of-warranty iPhone 8 costs $149 according to Apple’s website. Khalid’s store can do it for $60, using an “after-market” part.

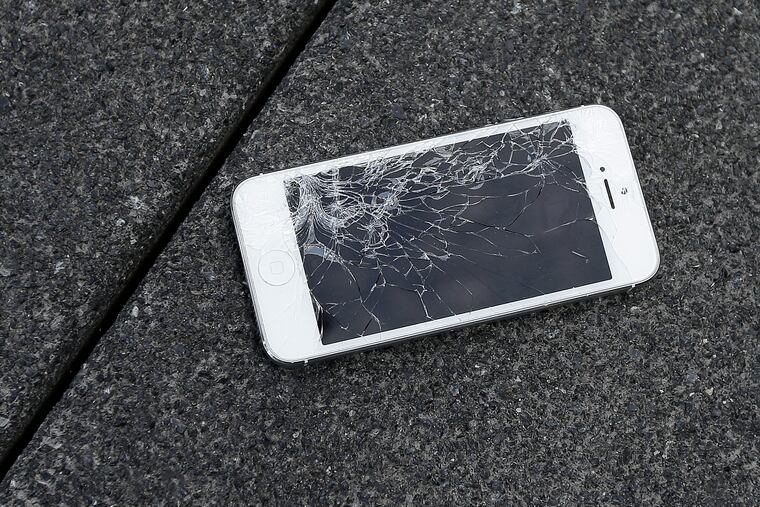

It was concerns about cost and convenience — and a cracked laptop screen — that led Montana State Sen. Steve Fitzpatrick, a Republican, to introduce a right-to-repair bill in his state this year.

“I was working on my computer trying to change out one of the screens,” he said. “And I was thinking, ‘Why do I have to send this out? We have guys around town that could do this.’”

But Fitzpatrick’s bill didn’t go anywhere during Montana’s short legislative session, the victim more of pressing priorities than outright opposition, he said. As for his own cracked screen, Fitzpatrick said he decided to get a new laptop rather than deal with the hassle of the Apple repair process.

Stateline.org is an initiative of the Pew Charitable Trusts.