How hackers used little-known credit-card feature to defraud Lansdale woman, $1.99 at a time

She was billed $1.99 by Google at least 64 times totaling $127.36 on six different credit cards. Capital One called it an "administrative error."

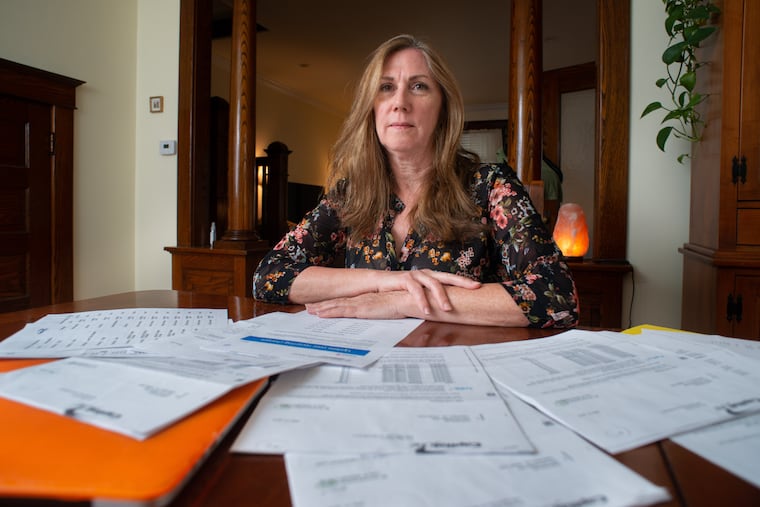

Whoever stole Leslie Robison’s credit card number could have bought a new computer, a flat-screen TV, or an expensive trip overseas.

Instead, the thief tried to scam her just two bucks at a time.

In January, Robison discovered more than a dozen charges at a $1.99 each from Google for hundreds of gigabytes of cloud storage she never ordered. She called her card issuer, Capital One, which refunded her and mailed a new card. But the charges returned each month through May, even as Google said it shut down the fraudulent account and Capital One sent more cards, Robison said.

In the end, she was billed 64 times totaling $127.36 on six cards over five months, according to credit card records. The charges didn’t stop until she canceled her account.

Robison, 61, of Lansdale, is the victim of a trend in credit card fraud in which criminals buy cheap, recurring digital subscriptions that largely go unnoticed by banks and consumers. Meanwhile, major companies now automatically receive updated credit card details when a customer’s card is lost or stolen, so recurring charges don’t stop. Thieves seize on that service to continue their frauds even when consumers get new cards, cybersecurity experts said.

“It’s exasperating and it feels invasive,” Robison said. “It feels like someone is robbing your house and everyone knows who it is but you, and you can’t stop it.”

Making matters worse was Capital One’s apparent inability to end the fraud. According to Robison, Capital One claimed only Visa could stop the charges because it offers merchants the account updater service. But Visa said it doesn’t update an account without a request from the customer’s issuing bank, suggesting Capital One was responsible.

In a statement, Capital One said it made an “administrative error."

“Our agents should have recognized the alternative process of getting the customer’s consent to be removed from the updater program,” said Capital One spokesperson Amanda Landers.

“Capital One has now resolved this for Ms. Robison and we recognized with her the inconvenience this caused, especially given the updater program typically is found to be very convenient for customers,” Landers said in a separate email.

A Google spokesperson said the web giant "identified and closed the accounts associated with the fraudulent charges.”

Criminals have realized that banks and other card issuers won’t investigate unreported charges if they’re less than $50, said Kayne McGladrey of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, which includes computer scientists and cybersecurity experts. Card issuers use algorithms tuned to spot expensive purchases, so criminals now buy a lot of items of little value, McGladrey said. For example, fraudsters buy streaming services such as Netflix and Spotify because banks may not find the charges unusual, he said.

“It’s low effort for them. Once they set up the subscription and unless the subscription is canceled, they don’t have to do any other work and they can resell access to that subscription," he said. "So it’s a guaranteed line of profit for them until somebody goes and notices there’s been a problem.”

Criminals typically resell access to the services on secondary markets, McGladrey said. Criminals may resell a streaming service that’s normally $10 per month for $5, netting the thieves $5 monthly. While a single crime is not that profitable, there have been cases where groups have reaped millions of dollars by charging small amounts to hundreds of thousands of consumers, he said.

In recent years, major credit card companies have offered account updater services to avoid disrupting recurring charges when new cards are issued. Medium to large businesses selling subscriptions -- from gym memberships to Amazon -- use the service to ensure they don’t lose customers who get new cards. Consumers are typically enrolled in these programs automatically through their card issuer’s service agreements, though they can ask to opt out, experts said.

“The unintended consequence is it is really easy for a threat actor to know [the consumer’s account] is going to be automatically updated,” McGladrey said. “So sure, [the consumer] got a new credit card number. The revenue stream is uninterrupted.”

Consumers should scrutinize their credit card statements for any unauthorized charges, regardless of how inexpensive, experts said. There are web applications such as Trim that help find unwanted subscriptions on your bill. Consumers should also dispute charges directly with the card issuer, which must stop unauthorized charges under federal law, said Ed Mierzwinski of the U.S. Public Interest Research Group.

“The credit card company and the merchant like to punt back and forth," he said. "The credit card company doesn’t want to lose the fees from the merchant, and it’s just a pain in the neck for consumers.”

Robison was charged for Google cloud storage to store emails, documents, and pictures. Google sells 100 gigabytes of storage for $1.99 per month. Robison was billed up to 14 times monthly, suggesting she was charged for 1.4 terabytes of storage, or enough space for half a million photos.

Letters from Capital One showed she disputed the charges at least five times. In addition, Robison said she spoke with the bank and Google on a three-way phone call in April, when Google determined that Robison did not purchase the storage. The charges continued anyway.

The headache didn’t end once Robison canceled her credit card account. When she tried to reopen a new one with Capital One this month, the bank initially denied her before ultimately signing her up, according to records and emails.

“It got to be kind of a game,” she said.

Robison is a personal coach and business consultant, so she sees a lot of people’s paperwork. Lately, she said she’s noticed $1.99 Google storage charges on clients’ bills, even though they did not authorize the charge.

“A lot of people choose to deal with the $1.99 because it’s two bucks," Robison said. “And it’s a lot more hassle to get it changed.”