The inside story of the 40-year journey to get to Villanova vs. Penn State

Villanova was scheduled to play Penn State in 1981, but the school's sudden decision to drop football meant the game never happened. Saturday, 40 years later, they'll face off in State College

Coming off a 6-5 season with a number of top players returning, Villanova running back Billy Conners and his teammates were looking forward to the following year, especially with a trip to vaunted Penn State on the schedule.

The year was 1981.

Saturday, when Villanova head coach Mark Ferrante and his 3-0 Wildcats trek up to State College to take on the undefeated and No. 6-ranked Nittany Lions, it will complete a 40-year journey. That’s because the 1981 game was never played after the Villanova Board of Trustees’ declaration that April to disband the 87-year-old football program immediately.

The decision rocked the campus and left players like Conners, fullback Craig Dunn, linebacker Anthony Griggs gutted. It uprooted student life and pushed many players to transfer and was especially surprising considering the school had just installed lights and AstroTurf at their stadium just months earlier.

Father John Driscoll, the then-president of Villanova, explained the decision at an April 15 news conference. ‘’For nearly 10 years, the expenses connected with fielding a major college football team have come under periodic review,’’ said Driscoll, who died in 2011. ‘’The Board feels that the university cannot in good conscience do other than re-evaluate its priorities and is intensifying its rededication to its academic mission.’’

“I was totally shocked,” recalled Conners, who said running backs coach Spencer Prescott delivered the news in the middle of the night on April 14. “I was returning for my fifth year. Spencer knocked on my door and told me Villanova had dropped football. I thought I was in a dream.”

» READ MORE: Penn State finding success through the transfer portal

Reality quickly set in for head coach Dick Bedesem’s players and staff. “We were clueless,” said Jim DeLorenzo, then the team’s freshman student manager, who later served five years as the school’s Sports Information Director before running his own public relations firm.

“A lot of kids showed up for spring practice the next day who didn’t know. They’re asking ‘what does that mean?’ We had a team meeting later that day. Dick [Bedesem] was stunned. The coaches had been out signing recruits that night. They get home and are told, ‘We dropped the program.’

“No one knew what would happen next.”

Where do we go now?

While the news might not have been a shock across the Delaware Valley, it reverberated throughout the Main Line, especially among alumni and former players. And one question remained: What would happen to all the players who had remaining eligibility?

“What happened when I went back to school was the gym was filled with coaches from all over the country,” said Dunn, now a minister, “I couldn’t count them all.

“Nick Saban [then an Ohio State assistant] was there and coaches from Penn State, Drake, Syracuse, Tulane, East Carolina. I visited Iowa State but signed with Ohio State and was a backup fullback for two years.”

Linebacker Griggs fared better at OSU, as did wide receiver Willie Sydnor at Syracuse, both setting the stage for brief NFL careers. Griggs played four years with the Eagles before finishing up in Cleveland, while Sydnor spent a year with the Steelers.

Meanwhile, three players -- Roger Turner, Todd Piatnik and Pete Giombetti -- took up the school’s offer to honor players’ scholarships if they stayed. Not only did they remain through graduation, they wound up captains on Andy Talley’s first team when football returned in 1985.

“I remember when they were recruiting me and brought me down a football game was part of the draw,” said John Pinone, who played basketball at Villanova between 1979-83, and ranks eighth on the school’s all-time scoring list with 2,024 points.

» READ MORE: Villanova ready to show 'we can play' with #6 Penn State

Bob Hope and the Committee to Restore Villanova Football

The Committee to Restore Villanova Football started slowly. But it eventually picked up momentum and financial support, enough to entice legendary comedian Bob Hope to come to town on Dec. 1, 1981 for a fundraiser at the Academy of Music.

“We put together a cocktail party at the Bellevue Stratford [Hotel] before the show,” said Charlie Johnson, captain of Villanova’s 1961 Sun Bowl-winning team and one of the leading voices of the committee.

“The place was filled and we made enough to keep us going. Plus, we got about $5 million in free advertising from the papers because of Bob Hope. We called it ‘Hope for Football.’”

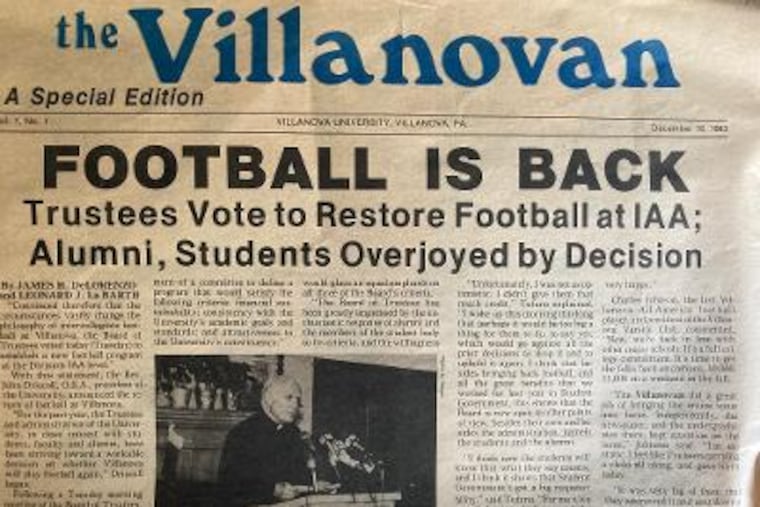

It still took two years until the board of trustees reversed its decision by announcing football would return on Dec. 13, 1983.

“During those years the university realized it had dropped a notch in prestige and how people viewed it,” explained Craig Miller, former Villanova SID from 1981-90 and at one point then-assistant basketball coach Jay Wright’s roommate. “And there was certainly a drop-off in alumni giving.

“People would send checks and write VOID on them, saying they wouldn’t continue to make donations until football returns.”

Having finally agreed to reinstate football, the next step for the board was hiring a coach capable of putting together a program from scratch. That challenge intrigued Talley, who grew up just down the road in Havertown, and was then head coach at Division III St. Lawrence in upstate New York.

But he was hardly their first choice. Talley even had to pay his own way down for an interview. But having the backing of Eagles general manager Jim Murray opened the door for a second interview.Talley, lugging a binder notebook filled with statistics and answers to all their potential concerns, wowed the board.

“When I got done I closed the book and Tom Labrecque, [former] president of Chase Manhattan Bank, said ‘That’s the best interview I’ve ever witnessed,’” Talley said. “And I knew I had the job.”

Staying over at his mother’s house, confirmation came when he was awakened by a 2 a.m. call from athletic director Ted Aceto asking him to come over to sign a contract.

The Talley era

The Talley era began on May 29, 1984, and lasted 32 years. During his tenure, Talley’s Wildcats won 230 games and six conference titles, culminating with the 2009 FCS National Championship. While no one then — himself included — could have imagined how it would play out, Talley was confident from the start that he’d succeed.

“I had already been in rebuilding programs at Middlebury, Brown and St. Lawrence,” said Talley, who was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 2020. “I knew what it was like to take over a program that didn’t have anything going for it. The most important things you need are good players, a good quarterback and obviously the backing from the university to do what is necessary in terms of recruiting. Recruiting was actually easy because you could promise a kid he could start for four years.

» READ MORE: Penn State's 3-0 start feels different this time under James Franklin

“So the first year it was all freshmen. The second year got a little harder, because I didn’t want to do it with transfers. So you can imagine this 41-year old coach, a local boy comes in here when Villanova wanted no part of football or me. I had to build a lot of friends and make sure our kids did it right.”

That was the message Talley delivered to his fledging Wildcats with the house packed for a Nov. 3, 1984 Blue/White scrimmage. But they didn’t play for real until Sept. 2, 1985, l, opening a makeshift schedule with a 27-7 win over Iona.

“Andy came in and had the ability to offer me playing time,” said offensive lineman and Norristown native Dave Pacitti, who transferred in after playing a year at Duke and is now CEO of Siemens USA. “Villanova had a strong academic reputation and most of the kids had grown up knowing Villanova football.

“The cool thing about it [was] everyone played three years together, which is really rare. Coach Talley was a great motivator and we were on a mission; maybe naively [we] thought we could do something.”

They did, going 5-0 that first season, and 8-1 the second year.

As they were preparing to enter the 1-AA Yankee Conference in 1987, Talley convinced Mark Ferrante, his former quarterback at St. Lawrence, to join his staff.

Ferrante is now Villanova’s head coach after waiting in the wings for three decades until Talley stepped down in 2017.

“It’s been a great community for me and my family,” he said.“It was never predetermined we’d stay this long. It just worked out and we chose to stay the course.”

Coming full circle

As pained as they were at the time by the Board’s decision, some of the Wildcats who were there in 1981 have made amends with the school which has since welcomed them back.

“I think all of us who transferred had built relationships that made our Villanova experience more special,” said Conners, who remains close friends with a number of his former teammates. “We realized what we had together was really unique and there was lot of bitterness it was taken away.

“I wish some of the people who did this could see the outcome; see the caliber of individuals they chose to pull the rug out from under. It’s a special group of good people.”

Among them was Howie Long. A second-round pick by the Raiders in the 1981 NFL draft — just weeks after the program had been dropped — Long went on to forge a Hall of Fame career, though he was often teased about playing at ‘Villa-nowhere.’

But that didn’t stop Long, who met his wife Diane at Villanova, from returning for his 1995 induction into the university’s hall of fame. He’s remained an avid Wildcats supporter, recently donating $1 million for what they’ve named the Howie Long Strength and Conditioning Center.

Clearly, a lot can happen in 40 years, several of the principal figures from that time — Bedesem, Aceto, Driscoll — are gone. But the lives of many others who were disrupted by a decision they still question today, have flourished. They’ve become leaders in their respective industries, pillars in their communities.

Yet for all their successes, all the lifelong camaraderie forged out of such trauma, they can’t help but often turn their thoughts towards those who helped them along the way but are no longer here to share in their accomplishments.

That’s the kind of legacy their current Wildcat successors will try to live up to Saturday when they take on Penn State for the first time in 70 years.

» READ MORE: CFB Games to watch: Notre Dame QB Jack Coan faces former school Wisconsin