Will Shortz is moving the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament to Philadelphia

The tournament, now in its 48th year, was the subject of the 2006 documentary "Wordplay."

In nearly five decades of directing puzzle competitions, New York Times crossword editor and NPR puzzle master Will Shortz has encountered a cheater only once, at a Sudoku championship in Philadelphia.

Luckily, Shortz doesn’t hold it against us. That came across loud and clear when he recently announced he’s moving the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament from Connecticut down to Philly next year.

“Philadelphia has a cultured audience,” Shortz said when we spoke this week. “It’s just a great city to have a major literary event at.”

The first time I heard of the ACPT was while watching Wordplay, a 2006 documentary about crossword puzzles featuring Shortz; the latter half of the movie is set at his annual tournament. I loved the movie when it came out and on a rewatch 20 years later, it’s still as quirky and delightful as ever.

In the film, the late puzzle constructor Merl Reagle, who crafted crosswords for the Times, The Inquirer, and other papers across the country, calls the ACPT an “orgy of puzzling,” which is a fantastic phrase that I’m guessing he never got into a puzzle and one that’s probably responsible for the film’s perplexing PG rating.

The play-by-play

Shortz — who designed his own major in enigmatology (the study of puzzles) at Indiana University — founded the ACPT at the Marriott in Stamford, Conn., in 1978 when he was just 25.

“There had not been a crossword tournament in the country since the 1930s, so we were starting fresh,” he said.

The first tournament attracted 149 contestants. This year, there are 926 competitors, with a long wait list, and after 48 years at the Stamford Marriott (aside from a few years the tournament was held in Brooklyn), the ACPT has just outgrown the space. The tournament will be held there for the last time in April.

Shortz and his team looked for new venues around the Northeast and settled on the Liberty Ballroom at the Sheraton Philadelphia Downtown, where they can accommodate up to 1,250 contestants.

The tournament will be held there from April 30 to May 2 next year.

“I’m hoping with 1,250 seats we won’t have to turn anyone away next year,” Shortz told me. “My goal is for everyone to come who wants to.”

The ACPT is held over three days and consists of eight rounds of puzzles. All contestants compete in the first seven rounds, which, much to this Luddite’s delight, are still done with pencil and paper.

“I want everyone to compete equally,” Shortz said. “Some people are very fast with their fingers so I wouldn’t want the tournament to depend on your computer literacy.”

Contestants are scored based on accuracy and completion time. There are multiple divisions, with an eighth round of playoffs held for the top three divisions.

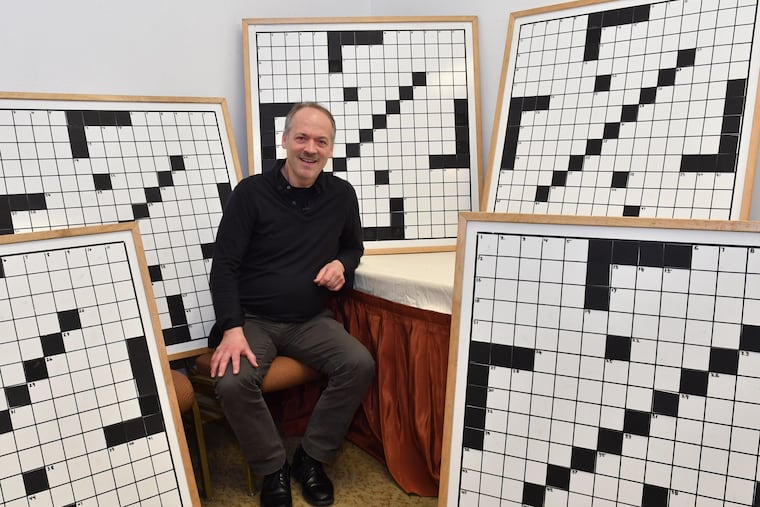

The A and B division playoffs are held on stage, with top three contestants working on giant crossword puzzle white boards before a live audience (and you thought completing a Saturday Times puzzle by yourself was intimidating!). Play-by-play announcers even call the games, so competitors must wear noise-canceling headphones.

The division A winner gets a $7,500 prize and crossword glory for a year. The last two tournaments were won by Paolo Pasco, a 24-year-old crossword puzzle constructor and seven-time Jeopardy! winner who’s competing in the quiz show’s Tournament of Champions this month.

Aside from the competitive games, there are also informal word games, a puzzle market, and a contestant talent show.

‘No judgments’

Shortz has never missed a tournament, except for when it was canceled in 2020 due to COVID. Even after suffering a stroke in 2024, he showed up to the tournament, just two months later.

“I was in a subacute rehab center and everyone was advising me not to leave the center, but there was no way I was going to miss the tournament,” he told me. “When I came in a wheelchair, everyone stood up and applauded and that brought tears to my eyes.”

Donald Christensen, who has attended the ACPT since the 1980s and serves as the event photographer, said the contestants are “a microcosm of society.”

“When you attend one of the tournaments, you are among a group of about 1,000 people who make no judgments about you or your abilities, and who are often very willing to share their secrets to successful solving with anyone who is interested,“ he said via email.

I enjoy crossword puzzles, but I’m absolutely terrible at them, so much so that I question my college majors (nonfiction writing and communications), my career, and whether I actually speak the English language. But there’s even room for someone like me at the tournament — a noncompetitor option, where you can play but your solutions aren’t scored. Spectator-only tickets are available for the Sunday playoffs, too.

Contestants aren’t allowed outside help, but they’re not required to hand over their cellphones either. Shortz said referees would see any cheating and looking something up on a phone would just slow down a good contestant.

“It’s not a group that would cheat anyway,” Shortz said.

The Sudoku swindler

And that brings me back to the stupefying Sudoku scandal of 2009. For three years beginning in 2007, The Inquirer sponsored the National Sudoku Championship at the Pennsylvania Convention Center, with Shortz serving as host (The Inquirer and Shortz also partnered to host the World Sudoku Championship here in 2010).

During the 2009 competition, a before-unknown player, Eugene Varshavsky of Lawrenceville, N.J., qualified for the finals in lightning time. But when he got on stage with his hoodie up for the championship round, he froze.

“It was a challenging puzzle but not crazy hard and he was utterly unable to finish it,” Shortz said. “It was kind of embarrassing for someone who’d solved the previous puzzle quickly.”

Still, Varshavsky was awarded third place, which came with a $3,000 prize. But puzzlers raised suspicions and the money was frozen while officials conducted an investigation.

Varshavsky was asked to come to The Inquirer to complete additional puzzles to prove his ability.

“We gave him the round-three puzzle he whipped through in the competition, which he was now unable to do,” Shortz recalled.

He was subsequently stripped of his title and the prize money. Shortz said officials believed he was getting help through an earpiece during the competition, though that was never proven. Coincidentally, a man by the same name was suspected of cheating in 2006 at the World Open chess championship in Philadelphia.

United by words

Philadelphia’s puzzle history isn’t all sordid though. We were home to the oldest known Times crossword puzzle contributor, the late Bernice Gordon, who constructed puzzles for decades and was the first centenarian to have a puzzle published in the Times.

And in 2021, Soleil Saint-Cyr, 17, of Moorestown, became the youngest woman to have a puzzle published in the Times.

With all of the talk around AI today, I asked Shortz if humans are still better at crafting crossword puzzles than computers.

“Of course, computers can create crosswords now, but it takes a human mind to create a brilliant crossword,” he said. “Only humans can still come up for a clever idea for a new theme and only a human can write a good, original crossword clue.”

Perhaps there is no better place for the American Crossword Puzzle Tournament than right here in Philadelphia, where words birthed our country into existence. We’re still writing the story of our nation and trying to figure out if this puzzle can be solved, but as in Shortz’s tournament, people are still united by words and creating small moments of order amid the chaos.

“We’re faced with so many challenges every day in life and we just muddle through and do the best we can and we don’t know if we have the best solution,” Shortz said. “But when you solve a crossword puzzle … it gives you a tremendous feeling of accomplishment. You put the world in order.”

For more information on the ACPT and how to add your name to the 2027 contact list, visit crosswordtournament.com.