A former Philly drug kingpin, once ordered to life behind bars, had his sentence reduced to 25 years

A federal judge ordered the sentence reduction for Alton “Ace Capone” Coles. His lawyers cite a “remarkable” turnaround.

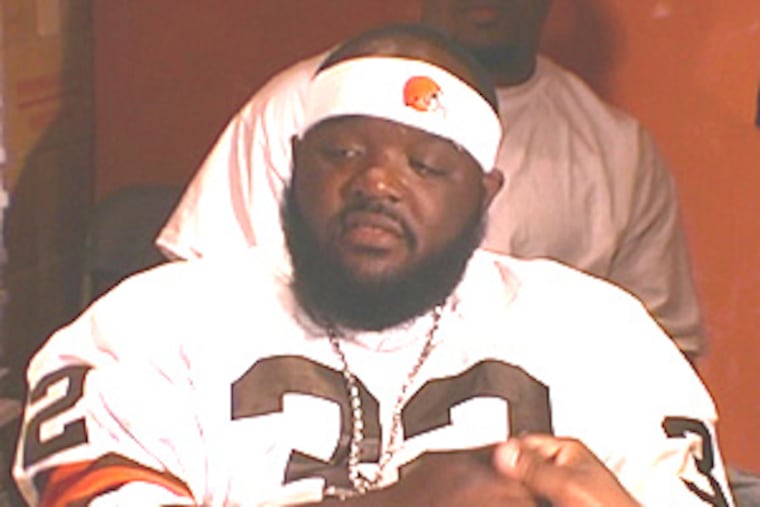

In 2009, after a federal judge effectively ordered Philadelphia drug kingpin Alton “Ace Capone” Coles to die in prison — imposing a life sentence plus 55 years for convictions on a host of drug and weapons charges — Coles momentarily dropped the swaggering persona he had displayed while building his vast cocaine empire.

“I never thought it would come to this,” Coles said at the time, his voice cracking as he spoke in court. “I don’t think life is deserved for selling drugs.”

On Tuesday, another federal judge offered something close to an endorsement of that view as she ordered Coles’ sentence be reduced to 25 years in prison — meaning Coles, now 52, could be released within a few years.

Coles’ twist of fate is the result of a complicated appellate process, one that has its roots in how federal laws have changed in recent years for some drug crimes, particularly those involving crack cocaine. The penalties for crack offenses were once significantly harsher than those tied to other narcotics, leading to widespread racial disparities because most defendants in crack cases were Black.

Coles’ lawyers say his case is also a demonstration of the “remarkable” turnaround Coles has made behind bars. While Coles once oversaw a drug operation that was estimated to have poured $25 million worth of cocaine and crack into Philadelphia — all as he served as the brash face of a local hip-hop record label — in prison, his lawyers said, he has become a barber, facilitated anti-violence programs for other inmates, and served as a counselor for prisoners with thoughts of self-harm.

“Knowing that he was facing the rest of his life in prison, Mr. Coles engaged in this extraordinary effort toward rehabilitation for the sole purpose of improving his life and of those around him,” his lawyer, Paul Hetznecker, wrote in court documents.

Federal prosecutors took a starkly different view, saying that Coles was “one of the major drug kingpins in Philadelphia during the last several decades” and that his eligibility to be resentenced was the result of a “pure technicality.” Even if Coles had committed his crimes today, prosecutors said — after Congress changed criminal sentencing guidelines — his actions would still warrant a life sentence.

“Coles led an armed and violent cocaine and crack distribution gang, which distributed quantities of deadly narcotics that [the trial judge] at sentencing aptly described as ‘staggering,’” prosecutors wrote in court documents.

U.S. District Judge Kai Scott said she believed that Coles had transformed his life in prison, and that 25 years of incarceration — even if much shorter than a life sentence — was still a substantial amount of time to serve behind bars.

Discussing Coles’ growth since being convicted, Scott said: “I’ve never seen this type of post-sentence rehabilitation.”

Coles, meanwhile, apologized for his crimes, telling Scott he is determined to try to make amends for his past.

“I am not the man I once was,” he said.

Building an empire

When Coles was federally indicted in 2005, prosecutors said he had run one of the largest drug organizations in modern city history. Coles and his coconspirators, they said, helped push a ton of cocaine and a half-ton of crack into the streets over the course of more than six years.

Coles was not charged with any crimes of violence, but federal authorities said they believed his group and its members were tied to nearly two dozen shootings and seven homicides.

As he was growing his drug empire, Coles was also building his reputation in the local rap scene. He helped found the hip-hop label Take Down Records, and staged popular parties and concerts around the city.

And he and a friend, Timothy “Tim Gotti” Baukman, produced and starred in a 31-minute music video called New Jack City, The Next Generation, in which they portrayed Philadelphia drug dealers who used violence and intimidation to cement their standing in the underworld.

Authorities used that video as part of a two-year investigation into Coles and his gang, and said Take Down Records amounted to a front for Coles to wash his money. They also wiretapped hundreds of conversations between drug associates, and went on to seize dozens of weapons and hundreds of thousands of dollars in raids on members’ homes.

Coles was charged in 2005, as were nearly two dozen associates, some of whom pleaded guilty or went on to cooperate with authorities.

Coles took his case to trial and testified in his own defense, saying he was not the kingpin prosecutors made him out to be.

But in 2008, a jury found Coles guilty of crimes including conspiracy to distribute cocaine and heading a continuing criminal enterprise. U.S. District Judge R. Barclay Surrick later sentenced Coles to life behind bars plus 55 years, saying: “The amount of drugs was staggering and the money involved was even more staggering ... this crime was just horrendous.”

Ongoing legal saga

The imposition of that penalty, however, was hardly the end of the legal drama connected to Coles.

After Coles was sentenced, a Philadelphia police officer was convicted and imprisoned for tipping Coles off about his impending arrest.

A federal appeals court also later overturned a conviction tied to Coles’ girlfriend, who had been accused of helping him launder drug money to buy a house.

And Coles continued to file appeals challenging his case.

In 2014, he successfully argued to have one of his two prison sentences — the 55-year term — reduced to five years because of technicalities in how evidence was used to prove certain charges. His life sentence, however, remained intact.

But in 2020, Hetznecker, Coles’ appellate lawyer, filed a new motion challenging that penalty, saying a law passed by Congress in 2018 made Coles eligible to have his life sentence reduced.

The law, known as the First Step Act, was a sweeping attempt to undo some of the tough-on-crime laws from the 1990s that caused the federal prison population to swell. The bill received bipartisan support, and was signed into law by President Donald Trump.

One of the law’s provisions allowed some people who were sentenced for crack-related offenses to have their penalties reevaluated — part of an effort to unwind the racial disparities caused by disproportionately harsh sentences being imposed on Black defendants in crack cases.

Hetznecker, in seeking to have a judge reconsider Coles’ penalty, wrote that a life sentence “for a non-violent drug offense is a draconian sentence and, given the current paradigm of criminal justice reform, counter the movement toward a more just system.”

“The underlying principles of justice and fairness require that those subjected to punishment for crimes against society, especially those convicted of non-violent offenses, be provided the opportunity for re-integration back into society as rehabilitated individuals,” Hetznecker wrote.

Scott, the judge, agreed last month that Coles was eligible for a new sentence under the First Step Act. And in imposing the new penalty Tuesday, she said she believed Coles was unlikely to commit similar crimes in the future.

“It’s clear to me that you have been deterred — you have made changes,” she said.

Coles said he recognizes that he had once been “a negative influence on society,” but said he has now committed to bettering himself and trying to help others.

Hetznecker said Coles deserves the opportunity to demonstrate that he has moved beyond the persona he once inhabited on the streets.

“‘Ace Capone’ is dead, he’s gone,” Hetznecker said. “Alton Coles has emerged.”