Howard Mudd’s star-laden Eagles legacy lives on with Jason Peters and Jason Kelce | Jeff McLane

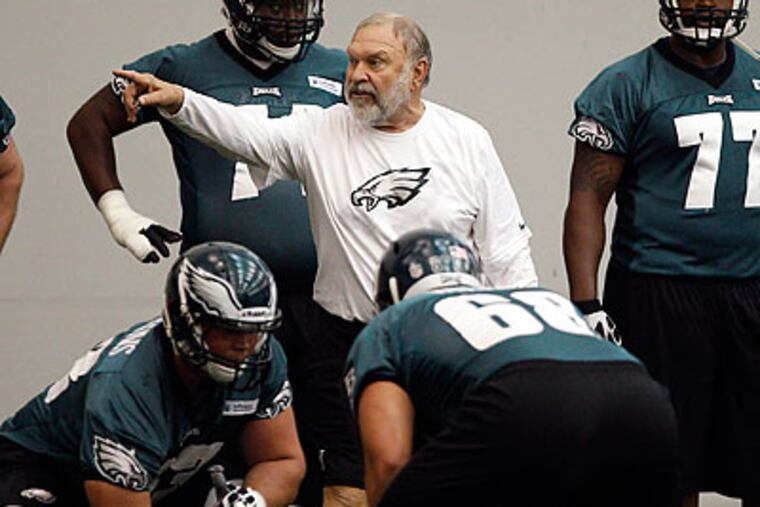

Mudd, who died this week at 78 and coached the Eagles offensive line for two years (2011-12), helped make Peters, Kelce and Evan Mathis great at their positions.

Howard Mudd once told a story about Jason Peters — it didn’t exactly reflect well on the Eagles tackle — under the condition that it couldn’t be reported unless Peters confirmed it happened.

It wasn’t a simple request. Peters talks about as much as Garbo, strikes an imposing figure, and isn’t often keen on provocative questioning. The interview never occurred, though, because the recording of Mudd — about 45 minutes of pearls of wisdom about Peters and the art of blocking — was somehow erased.

Thankfully, Evan Mathis, upon Mudd’s death Wednesday, recalled the anecdote.

It was the summer of 2011, after Andy Reid had lured Mudd out of retirement, after the NFL lockout had ended, and after one of the Eagles’ first training camp practices at Lehigh.

“Peters didn’t like something Howard was saying in a meeting,” Mathis recalled, “and J.P. said ‘Man, F--- you.’ Howard instantly replied, ‘F--- me? F--- you! And if you don’t like it you can go talk to Andy.’

“That was my first taste of Howard and a player getting into it. Not just any player, a future Hall of Famer. Howard did not discriminate.”

Mudd coached with the Eagles for only two seasons, but he left an indelible mark. He elevated Peters’ performance, was instrumental in the drafting and first-year starting of center Jason Kelce, and helped develop the journeyman Mathis into one of the best guards in the NFL.

His impact is still felt today with Peters chugging along at 38, slated to move to guard this season, and Kelce entering his 10th year coming off another All-Pro campaign.

Mudd’s tenure wasn’t without its blemishes. The Eagles, after all, won only 12 games over that span — Reid’s final two years in Philadelphia.

But if there was a disappointment, notably Danny Watkins, it was often because of a lack of want-to, not talent. Maybe Mudd could be faulted for not investing as much time in younger players or deep reserves, but he knew the goods, and if you weren’t maxing out your abilities, he had only so much patience.

“He was never out to make anything personal; his only intent was to serve the greatest good for the player and the team,” Mathis said. “Sometimes he would let emotions fly and seemingly berate someone until they started to defend [themselves]. It was that shift in attitude that he was looking for all along, and when he got it, he’d shift immediately to a state of joy and acceptance.

“The energy he would give off in these moments was akin to, ‘Hey, look who finally woke up and decided to join us!’ The elevated emotion would seemingly come from a place of ‘I believe in you, you’re better than this, why the f--- aren’t you doing what you’re capable of?’

“It was never blind rage or unwarranted behavior. Sure, it may be a little unorthodox to societal standards and it may be easily confused with toxic shame, but it was always coming straight from the heart with sincere intentions.”

Mudd’s approach turned off some, but most came around, especially those who understood there was a method to the madness. Even a perennial Pro Bowler with freakish athleticism learned to benefit from his teachings. Mudd said he never had another problem with Peters after their initial altercation.

Old-school innovator

He may have been an old-school motivator, but he brought innovation to the offensive line. An exceptional NFL lineman in his own right — he earned three Pro Bowls nods in an injury-shortened career — Mudd wasn’t especially large for a guard. But he was athletic, and as he transitioned to coaching he preferred linemen who were agile.

His prototype thrived in zone-combination schemes and space blocking. Mudd’s epiphany, though, came early in his coaching career, when he was first with the Seahawks. He was watching Seattle SuperSonics guard Dennis Johnson defend at the top of the key using a hand-check — back when NBA players could — and his hopping technique struck Mudd.

Why can’t offensive linemen protect the same way?

Mudd wanted his players to be aggressive rather than passive against the pass rush. He had a disdain for the vertical step when used in certain situations that would leave behind Juan Castillo students, like Winston Justice, who were unable to adapt to his preferred jump set.

“I was getting yelled at for stuff that Juan would say, ‘Good job,’” Justice once said of the difference between the two former Eagles O-line coaches.

But Mathis and Kelce, who had a clean slate with the Eagles, and Peters and Todd Herremans, who were gifted enough to acclimate, thrived under Mudd.

Another novelty was allowing his linemen to turn their backs on a defense — a technique previously forbidden by most coaches — to deliver a block, if necessary.

“His techniques allowed me to use my aggression and athleticism to their fullest potential,” Mathis said. “He was an absolutely brilliant human being whose ideas and methods were all the result of high-level calculations and years of data. He believed in his methods, but was always open to gaining perspective, accumulating knowledge, and adding more tools to his toolbox.”

He had about done it all by the time Reid came calling. Coached a first-ballot Hall of Famer in tackle Walter Jones. Won a Super Bowl with Peyton Manning and the Colts. He was retired in Mesa, Ariz., living in a development called Leisure World, and riding his motorcycles.

But Castillo had moved to defensive coordinator — still odd to write — and Reid needed a capable replacement. Mudd embraced the challenge and the Eagles drafted Watkins in the first round that offseason.

“To look at the potential that was there and then what actually transpired were two totally different things,” Mudd said later of Watkins, who lasted just three years in the NFL. “There was some kind of disconnect psychologically because it had nothing to do with the physical.”

But he struck gold with Kelce, a sixth-round pick. Even after he retired a second time following the 2012 season, Mudd never tired of talking about the “undersized” center. In fact, he never turned down an opportunity to go on about about his former Eagles or football with enterprising reporters.

The game and various motorcycle accidents had mangled his body. His knees were shot, and he needed an artificial hip in 2012. He walked with a severe limp, and when he stood was bent over at a 75-degree angle.

But he returned to coaching yet again last year with the Colts. He lasted only several months in a senior position but didn’t slow down even after what would be his final retirement. That he would die two weeks after a motorcycle accident on July 29 could be seen as either tragic or a fitting end to his 78 years on earth.

Some of Mudd’s former linemen viewed his death the latter way.

“There’s a signed Howard Mudd photo in my office with the message, ‘Stay down & keep your feet moving,’ ” Mathis said. “The origins are from my tendencies to use lazy techniques on the football field, but it has become a motto I live by.

“I’m so grateful to have crossed paths with Howard, and I’m going to miss that m-----.”

He isn’t the only one.