Where in the world is Elvis Costello? On his new album, he’s all over the place.

Shemekia Copeland and Adrianne Lenker also have strong new releases.

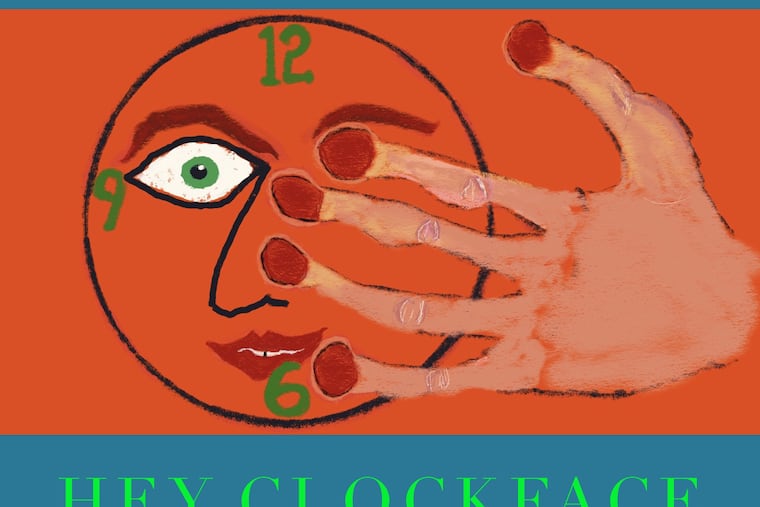

Elvis Costello

Hey Clockface

(Concord ***)

If Elvis Costello’s 33rd studio album sounds a bit all over the place, that’s because that’s where it was recorded.

The stupendously prolific English songwriter and former angry young man began work by cutting three solo songs in Helsinki in February. He recorded nine more in Paris, working with musicians anchored by his longtime pianist Steve Nieve.

Finally, two tracks were written by trumpeter Michael Leonhart in New York and recorded with guitarists Bill Frisell and Nels Cline, before Costello completed them post-lockdown in Vancouver.

Unsurprisingly, Hey Clockface lacks the cohesion of Look Now, 2018′s excellent return to form with his band the Imposters. Instead, it plays out as a melange of styles, a sampler that relates to various stages in Costello’s career.

“I Do (Zula’s Song)” has a smoky jazz club vibe that recalls Chet Baker’s heartbreaking turn on “Almost Blue.” Elsewhere, the arrangements bang and clatter with a claustrophobic rage reminiscent of 1986′s Blood & Chocolate. “No Flag,” bursts with bitterness and bile: “I’ve got a head full of idea and words that don’t seem to belong to me,” he spews. “No sign for the dark place that I live / No God for the damn I don’t give.”

The stylistic smorgasbord begins with “Revolution #49,” a spoken-word piece that unspools like film noir narration (“Life beats a poor man to his grave, love makes a poor man from a dagger / Love is the one thing we can save”).

The album hits a high point with the doomy, impressively realized “Newspaper Pane,” creating a dark, enveloping mood in which the jaunty New Orleans strut “Hey Clockface / How Can You Face Me” feels strangely out of place. This is not Costello’s most consistent work, but he still does have a head full of ideas, with most worthy of exploring.

— Dan DeLuca

Shemekia Copeland

Uncivil War

(Alligator *** 1/2)

In 2018, Shemekia Copeland addressed the state of the union, and her place in it, with the no-holds-barred America’s Child. Working again with Nashville producer-guitarist Will Kimbrough, who once more wrote most of the songs with executive producer John Hahn, the singer delivers another searing statement with Uncivil War.

The title song, accented by dobro and mandolin, is an aching lament about the divisions tearing apart the country, and reveals Copeland at her most tender and vulnerable.

Elsewhere, she unleashes the powerhouse voice that has long made her one of the most commanding presences in the blues and beyond. “Clotilda’s on Fire,” a blues-rocker with a blistering guitar solo by Jason Isbell, addresses the undying stain of slavery. “Walk Until I Ride” is a defiant gospel shouter that sounds like a long-lost civil-rights anthem, while “Money Makes You Ugly” is a nasty-riff rocker.

Copeland also audaciously tackles the Rolling Stones' famously misogynistic “Under My Thumb.” Here it is given a sinuous swamp groove punctuated by finger snaps, which highlights her in-your-face delivery as she flips the gender dynamics.

Also addressing sexual identity and female empowerment is “She Don’t Wear Pink,” a tangy roots-rocker with Duane Eddy on guitar. “Dirty Saint,” in another vein, is an infectious, New Orleans-flavored tribute to the late Dr. John.

And, as she often does, Copeland includes a song by her late father, the blues great Johnny Copeland, ending this righteously powerful set with the easy-rolling rhythm and sweet sentiment of “Love Song.”

— Nick Cristiano

Adrianne Lenker

Songs / Instrumentals

(Saddle Creek, ***)

Big Thief released two celebrated albums last year, U.F.O.F. and Two Hands, and were touring Europe when the pandemic sent the quartet home to Brooklyn in March.

Adrianne Lenker, regrouping from a breakup, decamped to a cabin in western Massachusetts, and decided to set up rudimentary equipment with the help of a producer-friend and make an acoustic solo record, which became two: a 40-minute set of 11 songs, and a 38-minute pair of instrumentals.

Instrumentals pairs “Music for Indigo,” a 21-minute acoustic guitar meditation that occasionally snaps into focus, with “Wind Chimes,” a 16-minute track of chimes and ambient environmental sounds. They’re pleasant and calming.

And Songs is often captivating. Lenker is uncommonly good at expressing raw emotions in succinct pictures, and here she contemplates loss, longing, and unrequited love. With Big Thief, songs often blossom from their folk-rock underpinnings into something full-blooded and insistent. Here, though, they are stripped to an acoustic guitar and her earnest voice, closely mic-ed with minimal overdubs, and they unspool with a sense of first-take immediacy.

In this unadorned setting, her thin voice sounds lonely, introspective and sometimes desperate; British folk icon Vashti Bunyan comes to mind.

Lenker’s acoustic guitar picking shimmers on the lovely “Anything” and is beautifully melodic on “Zombie Girl,” which has the perfect form of a Nick Drake composition — the birdsong in the background adds to the intimacy.

A handful of these songs, including “Dragon Eyes” and “Not a Lot, Just Forever,” rank with Lenker’s best even in this minimalist form, and the feeling of isolation and yearning is apt for our cautious time.

— Steve Klinge