The best that never won: After a record streak, a blown call ended the 1979-80 Flyers’ quest for a third Stanley Cup

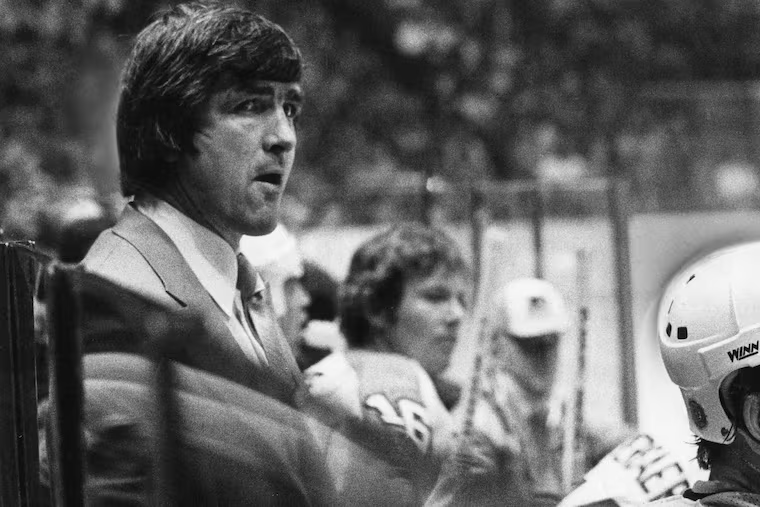

Pat Quinn's team went unbeaten for 35 games, and seemed invincible. But they came up short. First of a six-part series on the best teams to never win a championship.

First in a six-part year-long series about the best local teams that never won a championship. Today: 1979-80 Flyers. Coming in April: the 1976-77 Sixers.

When Pat Quinn replaced that day’s traditional practices with mandatory bonding sessions, during which his players could compete in anything but hockey, the Flyers coach began referring to Mondays as “Fun Days.”

Though the name sounded oddly genteel for a sport that celebrated grinders and goons, the weekly softball, volleyball, and touch-football games, followed by beers at Rexy’s or the Philadium, helped fuse the 1979-80 Flyers, a loosely connected roster of veteran minor-leaguers, talented prospects, and leftover stars from the franchise’s back-to-back Stanley Cup champions.

“We were together all the time,” said Bob Kelly. “If you didn’t blend in, you weren’t there very long.”

They drank together. They hung out together. They fought together. And they won together. Playing with a persistent pugnacity, they shot to the top of the NHL and stayed there, defeated only 12 times in 80 regular-season games.

But the 1979-80 Flyers suffered together too, never more so than when, hours after their season was jolted to a close in Game 6 of the Stanley Cup Finals, they boarded a bus for a journey back to Philadelphia that would be muffled by disappointment.

“That bus trip home,” goalie Phil Myre recalled, “it wasn’t a happy one.”

Until that Saturday before Memorial Day 1980, Quinn’s Flyers had seemed invincible. They lost once in their first 37 games, put together an NHL-record 35-game unbeaten streak spanning 86 days, compiled a league-best 116 points, won 11 of their first 13 postseason games.

Then suddenly on that afternoon in Uniondale, N.Y., in the last nationally televised NHL game in the United States for a decade, fate turned on them. The Flyers’ enchanted season, one of the most memorable in franchise history, concluded with a controversial 5-4 overtime loss to the Islanders, a defeat made more maddening by three questionable New York goals, one the result of a legendary lapse by linesman Leon Stickle.

“If we were going to lose,” Bill Barber, who had 40 goals that season, said nearly four decades later, “we didn’t want it to be that way.”

What really stung was the knowledge that had they beaten New York that day, Game 7 would have been at the Spectrum, where the 1979-80 Flyers won all but seven of 51 regular-season and postseason contests.

“The Islanders were really good, but I don’t think we’d have lost a Game 7 at home,” said Kelly, the turbo-charged left winger whose 10-year Flyers career ended that day. “But what can you do? They didn’t have replay yet and Leon Stickle sucked.”

“We’re proud of the streak and what we accomplished. But we were there to win a championship. And we fell short.”

Every hockey season yields a harvest of physical and mental anguish. The bumps and bruises eventually disappear. The psychological hurts, especially those untreatable “what-might-have-been” wounds, linger. Even now, almost four decades later, those Flyers lament their lost opportunity.

“You talk about being depressed and disappointed,” said Barber, 66, now a Flyers scouting consultant. “When you put in the kind of year we did, holy moly, a championship would have been icing on the cake. We’re proud of the streak and what we accomplished. But we were there to win a championship. And we fell short.”

Most would never win another Stanley Cup. Quinn would coach 18 more NHL seasons without one. And only two of the 26 players who wore the Black and Orange in 1979-80 would subsequently get a championship – Ken Linseman and Tom Gorence with the 1984 Oilers.

» RELATED: Meet the Six Flyers whose careers spanned from the first Stanley Cup to the 35-game unbeaten streak

Building toward greatness

It’s hard to say when the transformation of the 1979-80 Flyers began, when a team apparently in decline morphed into a juggernaut. Their schedule would suggest it happened after their second game, a 9-2 blowout loss in Atlanta on Oct. 13.

“We absolutely got blistered,” Barber recalled. “I remember thinking, 'Wow, if this is how it’s going to be, we’re all going to be embarrassed.’ But that’s not the kind of team we were. We came together and we started winning. And we didn’t lose until January.”

Others pointed to the morning Quinn stormed off the ice during a practice at the University of Pennsylvania’s Class of 1923 rink. If it was a motivational ploy by the second-year coach, it worked.

“Bobby Clarke got us together on the ice,” recalled goalie Pete Peeters, 62, a retired goaltending coach for several NHL teams. “We all felt like we’d disrespected Pat.

"Then we went and bag-skated ourselves,” he said, referring to drills usually reserved for punishment.

Myre thought the spark came later, when an oddly timed team meeting in November helped turn an impressive streak into a historic one.

“We’d just won at Los Angeles and Vancouver [pushing it to 16] and Bobby Clarke called a players-only meeting,” said Myre. “He was ticked off with how we’d played. His message was that if we kept it up, we wouldn’t be successful. Everybody was like, 'What are you doing, Bobby? We won both games.’ But he was clear. That was a turning point for us.”

That run of 25 victories and 10 ties, still the longest in the major professional sports, shocked everyone, especially those who’d picked Philadelphia to finish behind both New York teams in the Patrick Division.

The prognosticators’ pessimism was understandable. In the four seasons since winning consecutive Cups in 1974-75, Philadelphia’s victory total had dipped annually – from 51 to 48 to 45 to 40. And when Quinn replaced the fired Bob McCammon in January 1979, he became the Flyers’ third coach in eight months.

“When we started to slip, everybody loved to bury us. We were not the most loved team in the league.”

“When we started to slip, everybody loved to bury us,” said Mel Bridgman, who replaced Clarke as captain in 1979-80. “We were not the most loved team in the league.”

Nor, on paper, the most impressive. Clarke was only 30, but the grind of centering the first line, killing penalties, and taking his turn on power plays had worn him down physically. Peeters was an untested 22-year-old goalie. And the defense was a mess, so banged-up and thin that Quinn summoned three longtime minor-leaguers to help.

“If you looked at our team in the beginning of the year and heard someone say we were going to go 35 games without losing and get to the Finals, you’d have laughed,” said Barber.

But after that spanking in Atlanta, the Flyers wouldn’t lose until the decades changed.

“So many people around the league came up to me and said, ‘How the heck are you guys doing this? With mirrors?’" Quinn, who died at 71 in 2014, told the Inquirer in 1990. “They’d see defensemen like Norm Barnes, Mike Busniuk, and Frank Bathe and a winger like Al Hill and they just couldn’t understand how we were able to play so well.”

» FROM 2014: Former Flyers coach Pat Quinn remembered fondly

Much of the credit had to go to Quinn, a gruff, 36-year-old former defenseman who liked cigars and three-piece suits, who ran crisp practices and cozied up to his players.

“He reminded me of Doug Pederson,” said Kelly. “He had a good feel for us and for chemistry. He was a player and he knew how to put people together.”

As a player, Quinn had been a plodding but chippy blue-liner. Behind the bench, though, he was surprisingly laid back, a coach who rarely lost his cool.

“He reminded me of Doug Pederson. He had a good feel for us and for chemistry. He was a player and he knew how to put people together.”

“I played with Pat in Atlanta and he was mean,” said Myre. “But as a coach he wasn’t. He didn’t try to change people. He let you be yourself. We had a highly disciplined, very competitive team. We didn’t need a lot of verbal or psychological motivation. That was really contrary to what we were used to.”

Quinn shook things up. He made Clarke a playing assistant coach and reduced his on-ice workload. He gave the captain’s responsibility to Bridgman and more playing time to sniper Reggie Leach, who responded with a team-high 50 goals.

He got insurance for Peeters by acquiring Myre in a trade with St. Louis. Looking for a two-way line, he teamed rookie Brian Propp, aggravating center Linseman, and Paul Holmgren. They would outscore the Clarke-Barber-Leach line and drive opposing lines to distraction.

But his most prescient move might have been promoting several of the unspectacular players he’d coached with the Flyers’ Maine farm team, including Hill and “The Three B’s” — gritty defensemen Busniuk, 28; Norm Barnes, 26; and Frank Bathe, 25.

“In my opinion, our success was due to the ‘Three B’s’ back there,” said Kelly, 68, now a Flyers ambassador. “Nobody knew them, but they played really tough hockey. They stayed at home. They were old-school.”

While their penalty-minute total made it appear these were the same old Flyers, the 1979-80 team was actually transitioning from its brutish Broad Street Bullies days into a more freewheeling style, the kind Montreal had used in winning the previous four Cups.

“Pat was ahead of his time technically. He was one of the first coaches who had his wingers cut the zone in half, had them weaving through center ice,” Myre said. “It was different than the way things had always been done. Our guys really caught on, but a lot of teams had difficulty defending us.”

That’s not to suggest Quinn, whose playing-days highlight was his flattening of Bruins superstar Bobby Orr during a 1969 game at Maple Leaf Gardens, was developing an Ice Capades troupe.

For a ninth consecutive season, his Flyers were the NHL’s most penalized team. If their total of 1,844 minutes wasn’t quite up to the 1,980 they accumulated in 1976, it was 384 more than runner-up Boston managed.

“We still had the grit and the muscle factor,” said Barber. “We had a high compete level. All the guys battled for one another. Everyone understood their role. Nobody looked at how much ice time they got or any of that crap. It was strictly business.”

» FROM THE ARCHIVES: For 35 games, these Flyers were unstoppable

Holmgren (267) and second-year defenseman Behn Wilson (212), who replaced Dave Schultz as the primary enforcer, each finished in the top 10 in penalty minutes. Linseman, Kelly, Bridgman, Bathe, and Andre Dupont all topped 100 minutes.

“Behn Wilson was probably one of the toughest guys who ever played,” said Barber, “if not the toughest.”

Quinn’s four lines were anchored by returnees from the Cup winners — Clarke, Barber, Kelly, Leach, and Rick MacLeish — and supplemented by Bridgman, Linseman, Propp, and Holmgren, a physical American winger who had been mired on a checking line.

In addition to Leach’s 50 and Barber’s 40, Propp (34), MacLeish (31), and Holmgren (30) all topped 30 goals. No Flyer had as many as 80 points, Linseman leading the way with 79, Leach adding 76, Propp 75.

Myre and Peeters shared the goaltending and the latter surprisingly was among the league’s best (29 wins, a 2.73 goals-against average, and the team’s only shutout).

The streak

The streak began on Oct. 14, the night after the Atlanta embarrassment, with a 4-3 home win over Toronto. It wouldn’t end until Jan. 7.

By Dec. 1, it had reached 19 games (16 wins and three ties) and the rest of the hockey world was paying attention.

“Our forwards were so strong that it seemed like we were always playing with leads,” recalled Propp, 60, who lives in Cinnaminson. “Suddenly we had a 15-, 20-game streak and people started to take notice.”

The closest call came Nov. 3 against the four-time champion Canadiens in Montreal. Trailing, 2-1, in the third period, the Flyers pumped four goals past Montreal keepers Denis Herron and Michel Larocque in 6 ½ minutes for a 5-3 victory.

The NHL’s record unbeaten streak was 28 and the Flyers tied it – barely – with a 1-1 tie against Pittsburgh on Dec. 20 at the Spectrum. Trailing, 1-0, late in the third, Wilson knotted it up on a power play with 4 minutes, 8 seconds left.

Clarke said the only time he felt pressure during the streak was on the day they broke the record – Dec. 22 in Boston. Philadelphia responded with its best game of the season, a 5-2 victory that was as physical as it was entertaining. Wilson, Holmgren, and right-winger Dennis Ververgaert required stitches afterward.

“It was a masterpiece of a game,” Quinn said. “You could measure our desire that day in the number of stitches we took.”

At game’s end, Boston fans stood and applauded the new record-holders.

“What an awesome ride that was,” Myre recalled. “There were a lot of people who, because of the reputation of the Bullies, didn’t want us to break the record. So to get it in and to do it Boston was really sweet.”

With a 4-2 win in Buffalo on Jan. 6, the streak reached 35. By then Philadelphia had a 22-point lead in the Patrick Division.

The inevitable arrived with a thud. Before a hostile, frenzied crowd of 15,962, the largest ever at Minnesota’s Metropolitan Sports Center, the Flyers fell behind, 3-1, and never rallied in a 7-1 streak-busting loss to the North Stars.

“We knew it couldn’t go on forever,” said Bridgman, 63. “We just viewed each game as a chance to work on some of our shortcomings before the playoffs.”

The playoffs

There weren’t many shortcomings in evidence early. The Flyers swept Edmonton, with 19-year-old Wayne Gretzky, 3-0, in the postseason’s opening round. They topped the Rangers in five games in the quarterfinals, and in the semis got revenge on Minnesota, taking that series, 4-1.

Then came the Islanders and a 4-3 overtime loss in Game 1 that ultimately cost them a third Cup in six years.

“We’d been sitting around after beating Minnesota in five games and we lost some of our mojo,” said Barber. “That left us in a mess.”

Home teams won the next four games, setting up Game 6 in Uniondale. The 2:05 p.m. meeting would be historic for several reasons: It was the last Finals game played in the afternoon, the last NHL game televised nationally in the States until 1990. And there was Stickle’s slip-up.

It was 1-1 late in the first period when Islanders winger Clark Gillies dropped a pass for Butch Goring. Everyone saw the puck move back across the blue line into center ice – everyone except Stickle.

“It was very obvious,” said Propp, “so much so that I stopped skating, which I shouldn’t have done.”

Hearing no whistle, Goring fired a pass to Duane Sutter, who pushed the puck past Peeters for a 2-1 Islanders edge.

“Leon’s a great guy. It was just human error. Today that wouldn’t happen.”

Afterward, Stickle admitted he “blew it.”

“Maybe there was black tape on Goring’s stick and it confused me,” he said. “Or maybe I was just too close to the play. I just missed it.”

Stickle, 70, retired in 1998, after enduring years of abuse on Philadelphia visits. Myre said he bumped into him often and never failed to remind of him of it.

“Leon’s a great guy,” Myre said. “It was just human error. Today that wouldn’t happen.”

Over the years, many have come to recall Sutter’s goal as the game-winner, but the Flyers bounced back and regulation ended at 4-4. Then with just over 7 minutes played in overtime, Bobby Nystrom took a cross-ice pass from John Tonelli and slapped it past Peeters.

“I still think Nystrom was offsides,” said Myre.

In 1995, the Islanders retired Nystrom’s No. 23. Myre was there that night on a scouting mission for the Los Angeles Kings and had to watch that infamous goal replayed over and over.

“And every time they did,” said Myre, “I got hotter and hotter.”

The Flyers fell to second in the Patrick the following season, 13 points behind the Islanders. They’d reach two more Finals in the decade – losing to Edmonton in 1985 and 1987 – but by then Quinn was gone, fired midway through 1981-82.

All these years later, the Flyers continue their frustrating quest for a third Stanley Cup. And the team that came so close 39 years ago has never been forgotten.

“After that streak we lost a few games and people started to wonder if maybe we’d played over our heads,” said Barber. “But we regrouped and went to the Finals. That’s the kind of character that team had. We weren’t the most talented team in the league. But we were well-coached, had structure, and came to play every game.

“That was a team,” he said, “that should be studied.”