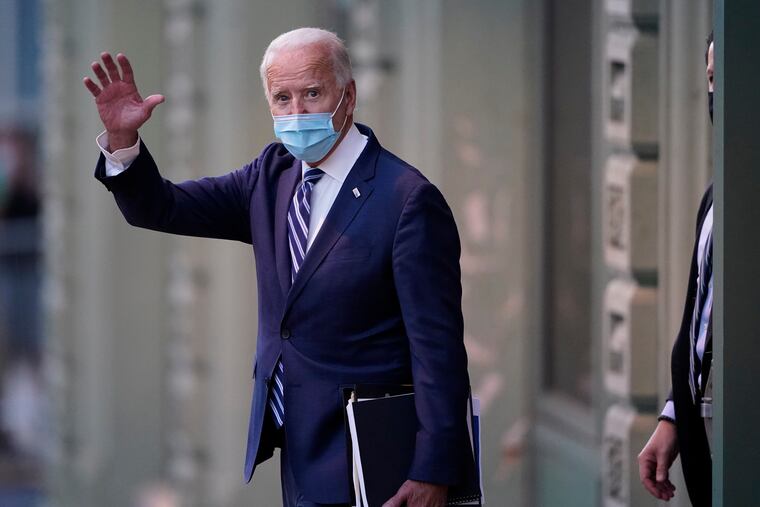

How Joe Biden could revamp worker health protections in the midst of the pandemic

The Trump administration has largely avoided taking major actions against companies when workers become sick or die. The Biden White House will likely change that, advocates say.

Worker advocates and former labor officials say they believe President-elect Joe Biden will push to revamp and strengthen the federal agency charged with enforcing workplace safety soon after taking office in January, a significant shift in the middle of a brutal pandemic.

The Trump administration has largely avoided taking major actions against companies whose workers became sick with or died of the coronavirus, and Biden has said he wants to ramp up enforcement to better keep workers safe.

A key focus is likely to be the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which is charged with upholding workplace safety. Biden could take action immediately at OSHA by ramping up inspections, filling vacancies and creating a safety standard that workplaces would be required to follow during the pandemic.

The incoming Biden administration already has a lengthy list of recommendations from which to work.

As the Biden campaign convened working groups over the summer to help conceptualize policy for a potential Democratic White House, a group of advocates — union representatives, former Labor Department officials from the Obama years, nonprofits and local groups — helped create a set of recommendations to reboot the agency’s approach to worker safety and in theory make companies adhere to a stricter set of guidelines to make workplaces more safe, some of the advocates who were part of the effort told The Washington Post.

Chief among these measures would be the creation of an “emergency temporary standard” for the coronavirus, a set of rules that workplaces would have to adhere to on such things as social distancing, handwashing breaks, communication during outbreaks and ventilation. Failure to adhere to these standards during inspections could result in penalties from OSHA.

“This is absolutely necessary and should have been done months ago,” said Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers. “You see the difference in a new administration that actually believes in worker protection and that workers are not dispensable.”

The Trump administration has resisted calls from former officials, Democrats and labor advocates to institute such a standard during the pandemic, saying that its existing safety rules and coronavirus recommendations are sufficient.

Critics say that OSHA’s regulatory power has suffered from understaffing and vacancies, and has been curtailed by the Trump administration.

» READ MORE: 2,200 Philly-area nurses are threatening to strike during a coronavirus surge for ‘safe patient limits’

OSHA said in a statement that the number of inspections completed in the last available year, 2019, were higher than in 2016 and that it has worked to replenish the ranks of inspectors. That was before the coronavirus struck, however.

There are also calls for the agency to review its whistle-blowing program, which is meant to protect workers from retaliation for complaining about “unsafe or unhealthful” conditions at work. (OSHA said in a statement that its rate of closure for these complaints has been in line with historical averages.)

Labor advocates say these changes — which could be among the first major changes to labor policy after Biden’s inauguration — could go a long way to reducing coronavirus transmission at workplaces, which has made for a significant portion of the pandemic’s toll around the country.

“Had OSHA issued an emergency standard, had they done enforcement instead of just guidelines, we know this spread could have been mitigated,” said Debbie Berkowitz, a former OSHA official. “What’s critically important is that OSHA is back on the job, to issue the standard and to get out there and do enforcement which will help mitigate the spread of COVID-19 — in work and in the public.”

Business groups, such as the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, have thus far opposed efforts to create an emergency temporary standard for the virus, signaling they would continue to push back on these efforts in the future.

“We don’t believe an emergency temporary standard is going to help employers protect employees,” Marc Freedman, a vice president at the U.S. Chamber said in an interview. Freedman said the group was concerned that such a standard would be burdensome for employers and increase the potential for costly and complicated litigation. He said the Chamber also believed a standard would not give regulators the flexibility they need to change guidelines if understanding of the virus’s spread continues to shift.

“It will create a whole new compliance and enforcement environment where employers will be liable for how they protect employees, not just whether they protect employees,” he said. “I think it creates a lot of concern for employers.”

» READ MORE: Philadelphia City Council expands access to coronavirus paid sick leave for low-wage workers

The Biden transition team declined to comment on specific plans but said that it was actively working on plans for the incoming administration.

“Joe Biden and Kamala Harris won the support of a majority of the American people in this year’s election, and have a mandate to pursue the policy platform that they ran on, including their plans to build back better in the wake of COVID-19 with an ambitious agenda to support workers,” the team said in a statement.

Biden’s public plans have long called for OSHA to institute an emergency temporary standard for frontline workers and step up enforcement by doubling the number of inspectors.

The Trump administration has declined to set such a standard during the pandemic, issuing only recommendations with such phrases as “if feasible” and “when possible,” which critics say do little to compel companies to act in the interest of safety.

When OSHA has enforced an existing safety rule, called the general duty clause, that requires companies to provide workplaces that are generally “free from recognized hazards” that are likely to cause death or serious physical harm, the penalties it has meted out have been paltry.

JBS, the largest meatpacker in the world, with a revenue of more than $50 billion last year, was given a $15,600 fine in September after 290 workers tested positive for the virus and six died at a plant in Colorado. Smithfield, which had a revenue of $14 billion last year, was given a $13,500 fine after 1,294 workers at a plant in Sioux Falls, S.D., tested positive for the coronavirus and four died.

“It’s like somebody turned the switch off,” Berkowitz said. “In the biggest occupational health crisis that the agency has ever faced, they decided to do nothing.”

During the critical early period of the pandemic through May, OSHA had issued only one citation, although it has since picked up the pace. It has now issued 204 citations for coronavirus-related issues, out of 10,295 complaints, resulting in penalties of about $2.8 million.

» READ MORE: ‘I’m not TSA. I’m a bartender’: Workers say they’re defenseless when customers don’t wear masks

Through the beginning of August, OSHA had opened up investigations for only 348 of 1,744 whistle-blowing complaints from workers who said they were retaliated against by employers during the pandemic.

Fifty-four percent of the complaints were dismissed or closed without investigation, and just 2% of the total were investigated and resolved, according to a report Berkowitz coauthored at the National Employment Law Project, a worker advocacy group.

While the numbers of complaints have surged during the pandemic, full-time staffing in the program, which investigates complaints, has declined.

OSHA has also been issuing scaled down press releases in recent months, a far cry from the more detailed releases about violations that former officials and advocates say were part of the agency’s work to not only stop but deter corporate wrongdoing, said David Michaels, who ran OSHA during the Obama years.

“The point of inspections and issuing fines is not solely to make that workplace safe, because if that were true, it would only impact a small number of workplaces,” Michaels said. “You issue a fine to send a message to other employers.”

A study of the Obama-era OSHA’s work to do regulatory “shaming” showed it was effective, finding that a single OSHA news release equated to a 73% reduction in violations in workplaces within a five-kilometer radius.

OSHA said in a statement that it decided to streamline announcements during the pandemic “to make it easier for the public to see all of the establishments that were issued citations related to COVID.”

In the absence of action from the federal government, workers and labor advocates have sought other means to compel employers to take workplace infections more seriously — and get OSHA to issue a standard.

Occupational health authorities in such states as Virginia and Oregon have passed emergency standards of their own, and another state, California, is in the process of drafting one.

Workers and labor unions have also filed lawsuits against OSHA, including the AFL-CIO, which sought unsuccessfully to force OSHA to create an emergency temporary standard. The U.S. Chamber filed a brief opposing the lawsuit.

The fight over OSHA has also animated stimulus debates on Capitol Hill, where Democrats have been pushing for the agency to step up its enforcement. The relief packages passed by House Democrats, in May and October, both included a requirement that OSHA pass an emergency standard for the virus within seven days of its passage. But the bills have languished in the Senate.

It is possible but unlikely that the emergency temporary standard will be included in a new stimulus package, should Democrats and Republicans find middle ground in the lame-duck session.

The United States has not done a detailed study of what percentage of infections have occurred through workplace transmission, but labor advocates believe the numbers to be high.

Tens of thousands of workers have fallen ill and many have died in such industries as meatpacking, groceries, and health care, but contact-tracing efforts have been spotty and inconsistent across the country in the absence of a robust federal effort.

“A lot of my employers were trying to do the right thing,” said Marc Perrone, president of the United Food and Commercial Workers International Union, which represents thousands of grocery, meatpacking and other food and agriculture workers. “Because there was no solid standard — the CDC kept changing — it was very difficult to get uniformity among our employers.”

Perrone said he supported the institution of an emergency temporary standard.

Singapore, which has done more robust contact tracing, has seen infections at workplaces range from 22% to 36% of total transmissions in the country, at various stages of the pandemic, according to local reports. In Oregon, where the state health authority is tracking workplace outbreaks with five or more cases, there have been at least 9,226 cases from workplaces — 18% of the state’s total — and 45 deaths.

“It’s clear that workplace exposures are making a major contribution to the pandemic,” Michaels said. “There are still uncontrolled virus exposure in many workplaces and if we don’t stop workplace virus transmission we’ll be unable to control the epidemic.”

The changes at OSHA represent structural shifts that Biden could do regardless of the opposition he faces from Republicans in the Senate. Under Trump, OSHA has never had a Senate-confirmed leader; appointee Loren Sweatt has lead the agency nonetheless, with many other senior officials in the agency’s organizational chart working in an “acting” capacity.