How Delaware County’s new public health agency fueled a fight over restaurant inspections

Delaware County's countywide health department launched in 2022 and has since been embroiled in a legal battle over who has the authority to conduct restaurant health inspections.

Even before Delaware County’s health department began operations in the spring of 2022, towns here were gearing up for a fight.

Years of planning went into the decision that a county of more than a half million people would benefit from an agency with the expertise to lead immunization campaigns and fight disease outbreaks.

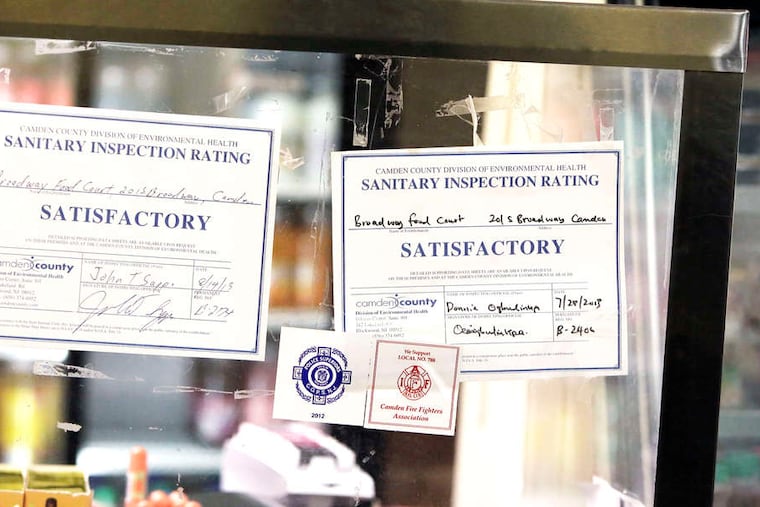

Improving the health of the community also meant the new agency would inspect restaurants for roach poop and their general sanitation.

Local townships balked. Some had already, on their own, been doing health inspections at restaurants for years.

And the legal battle that ensued over the restaurant inspections became a microcosm of larger disagreements, sharpened during the COVID-19 pandemic, about the appropriate role for government in protecting public health.

Thirteen towns in Delaware County are now entangled in a legal battle arguing that their local health inspectors knew business owners better and could resolve health violations at restaurants more quickly — and cheaply — than their counterparts at the county level.

The county has contended that coordination is key when it comes to food safety, and that a centralized health inspection system is crucial during emergencies involving outbreaks of foodborne diseases.

The court battle itself has set off new grievances: After a lower court barred the county from conducting restaurant inspections in 13 towns last year, town officials say that the county did not spray for mosquitoes in their communities that summer.

That’s one duty a countywide public health department should carry out, representatives for the towns say.

“Do you think a mosquito knows what township it’s in?” asked Frank Catania, the solicitor for Lower Chichester.

An appellate court ruled in favor of the towns earlier this month. It’s unclear what this means for mosquito spraying this summer.

County officials say they always aimed to provide first-class public health services throughout the county.

They blamed last summer’s spraying spat on court rulings that they said barred them from conducting any kind of environmental health operations in the townships involved in lawsuits over the restaurant inspections. That includes spraying for mosquitoes that carry blood-borne illnesses.

The rancorous court battle underscores the challenges involved in launching a new public health department in Pennsylvania, said Jennifer Kolker, a clinical professor of health management and policy at Drexel University, who assisted with efforts two decades ago to open a department in Delaware County and elsewhere in the state.

Back then, Kolker said, a particularly Pennsylvanian flavor of anti-government sentiment made it difficult to convince counties to launch their own health departments. The COVID-19 pandemic, which ushered in pushback against masking and vaccination requirements around the country, fueled more polarization.

Health departments like Delaware County’s might consider slowly expanding their duties to give wary communities time to build trust in the agency, she said.

“Health departments are only as good as the communities that trust them, especially right now, with such distrust of government and public health and science,” she said.

A new countywide health department

Until 2022, Delaware County was the only one of Philadelphia’s suburban collar counties that did not have a countywide health department.

But such departments are rare statewide; just seven counties and four municipalities have dedicated health departments. Counties without public health departments typically rely on the state for large-scale health initiatives.

A Democratic majority on the county council elected in 2019 voted to create a health department, but the project was delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic — which, supporters said, only underscored the need for a countywide department. Delaware County partnered with Chester County’s health department to address the pandemic.

In the debate over the need for dedicated public health agencies, many communities around the state have rankled at county-level oversight on health duties like restaurant inspections, Drexel’s Kolker said.

“People like health departments and governments when they’re doing things like spraying for mosquitoes, and they don’t like it when it’s ‘bad for business,’” said Kolker, who previously worked in Philadelphia’s health department.

Kolker said that it can be confusing for residents to navigate a patchwork of health duties divided between municipalities and counties.

“If a county health department is doing vaccines, but someone else is making sure wells are safe and restaurants are safe, I think it puts a lot on the public,” she said. “I don’t know how, as a health department, you have a cohesive plan if municipalities are opting in and out of different things.”

And, she said, restaurant inspections go beyond ensuring a restaurant is clean. Disease outbreaks spread through food can ripple beyond township borders, too. “Restaurant and food inspection is a core of public health,” she said.

‘Deeply concerned’

A lawyer for some of the townships involved in lawsuits with the county said they viewed the health department taking over restaurant inspections as an overreach.

“I think the municipalities have been doing things for 100 years, and COVID was an excuse for a lot of big government to come in and do a lot of things that didn’t need to be done and spend a lot of money,” said Jim Byrne, the county solicitor for Springfield Township, who also represented other municipalities in the suits.

Several larger towns, including Springfield, asked Delaware County Court to step in over restaurant inspections in the winter before the health department began operations in 2022. Another group of smaller towns sued or were sued by the health department after similarly pushing back on county-led restaurant inspections.

Seven towns scored a win earlier this month when an appellate court judge ruled that state law allows towns that had already been conducting their own restaurant inspections to continue doing so. A decision is pending for six others, county officials said.

Health department officials said they were “deeply concerned” by the ruling.

“This integration is absolutely critical during emergency events and outbreaks and is severely hampered by municipal jurisdictions acting individually and without information sharing,” Michael Connolly, a spokesperson for the county, wrote in a statement to The Inquirer.

Town solicitors said they are pleased with the court’s decision and are open to accepting services from the county health department that their towns do not have the capacity to undertake, like infectious-disease monitoring or vaccine clinics.

Catania and other solicitors said that their towns do plan to rely on the county health department to handle other duties that they are not capable of — like spraying pesticides to kill mosquitoes that spread blood-borne diseases like West Nile virus.

Do you think a mosquito knows what township it’s in?

He said the county received funding from the state to spray for mosquitoes countywide, and should have done so in communities contesting the restaurant inspections.

“By not spraying in an entire geographic area of the county, I think the health department is jeopardizing the health of everyone,” he said.

But, said Clifton Heights special attorney John McBlain, “[health inspections are] something we’ve been doing for years. We know the businesses and the owners. We know who’s a problem and who’s not a problem. From a local level, we’re quicker to respond to health problems than a county would be.”

McBlain said that local businesses had complained about the higher fees charged by the county health department for health inspections. But, he said, fees from health inspections were not a moneymaker for Clifton Heights.

“It’s not that we said, ‘Boy, if this revenue goes away, we’re in bad shape,’” he said. “It’s not something that raises general revenue. It relates reasonably to what it costs to run the local health program.”

What’s next for the county health department

Delaware County’s new health department’s restaurant inspections program has seen promising results, the county said, identifying more violations at restaurants, providing food safety education, and increasing oversight of septic systems and wells in the county.

The county is still permitted to provide immunization clinics, disease surveillance, and coordination for emergencies like natural disasters or disease outbreaks in townships that have opted out of restaurant inspections, the county noted in its statement.

Connolly, the spokesperson, did not respond to a follow-up question about whether the department’s environmental health division would spray for mosquitoes there.

The county can ask the Pennsylvania Supreme Court to consider another appeal in the case, but Connolly did not say whether it plans to do so.