After retired Black NFL players file lawsuit, experts weigh in on race and diagnosing dementia

Age and education are usually in the mix when doctors evaluate a patient.

Some diseases are relatively easy to diagnose. Take high blood pressure, which is diagnosed based on a simple test. Cancer diagnosis is often based on a biopsy.

Diagnosing dementia is not like that, said Jason Karlawish, co-director of the Penn Memory Center. It is what doctors call a “clinical diagnosis,” one that comes from conversations with a patient and, ideally, a close family member, along with a detailed medical and personal history. There are also medical and cognitive tests, but scores are considered in the context of the patient’s age and other social factors.

“It requires more judgment,” said Karlawish, who is a professor of medicine, medical ethics and health policy, and neurology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. If you just use raw test scores, “you will falsely label people.”

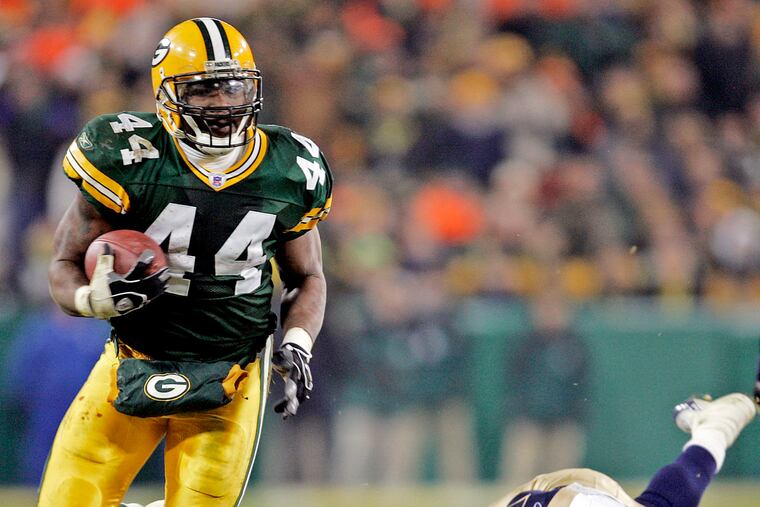

The question of adjusting cognitive test scores arose this week when two Black former NFL players filed a lawsuit alleging that the league uses racially based standards for dementia that make it harder for Black players to qualify for payouts given to those who suffered work-related brain injuries.

The suit said the NFL uses “race norming,” which assumes that Black players, on average, start with lower cognitive functioning. That means that Black players must perform worse than whites on tests of dementia to qualify for the diagnosis, the lawyers said.

According to the New York Times, the league said its statistical techniques were meant to account for demographic differences in age, education, and race. “The point of such adjustments — in contrast to the complaint’s claims — is to seek to ensure that individuals are treated fairly and compared against comparable groups,” it said. The league said doctors were not required to use any particular adjustments.

Mijail D. Serruya, a Jefferson Health neurologist, said of racial norming, “I have never heard of that,” adding that race is not well defined. Because changes in various kinds of thinking are normal as we grow older, age is commonly considered during cognitive testing. So is education, he said.

Karlawish said there are norms that consider race for some tests. “In America, what we find is there’s a tragic correlation between race and performance on cognitive testing,” he said. Comparing years of education may not adequately reflect disparities in the quality of education that Black and white people received, he said. Those differences are particularly important for the oldest generation of Black people. The adjustments are meant to keep people who don’t do as well on the tests from being wrongly diagnosed with cognitive impairment.

Overall in the United States, African Americans over age 65 are about twice as likely as whites to have a dementia diagnosis, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.

Karlawish said “the science is still out” on why. It could be a combination of genetics, socioeconomic factors that affect access to health care and lead to chronic diseases, and structural racism that causes chronic exposure to stress. Higher levels of education are associated with lower risk for dementia, possibly because highly educated people have more cognitive reserve and better cardiovascular health. Cardiovascular disease and diabetes raise the risk of dementia.

Serruya said patients often come in for evaluation with memory complaints. They may have started repeating themselves in conversations. Other common symptoms are having problems with finances, getting lost, abandoning hobbies or becoming more socially withdrawn.

He and Karlawish both said evaluation for dementia requires detailed conversations with patients and loved ones about how a person is functioning now and what they did in the past. Which schools did they attend? Were they good students? That helps doctors and neuropsychologists guess how patients functioned when they were younger.

The best norm, Karlawish said, would be a baseline test that shows “how did you do five to 10 years ago, but we don’t have that on most people.”

Doctors try to rule out other medical conditions, like fluid build-up in the brain, vitamin deficiencies, or strokes that might explain mental deterioration.

Evaluations are highly individualized, Karlawish said. Someone with, say, Barack Obama’s resumé might still do well on cognitive tests while in the early stages of dementia. Karlawish said he has sometimes given a dementia diagnosis to highly educated individuals who scored as normal on relatively easy tests like the Mini-Mental State Exam or the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MOCA). That’s the one President Donald Trump says he passed.

Karlawish will sometimes follow up with tougher tests. “That’s where you begin to show your evidence of impairment,” he said.

Testers also have to consider whether patients are native English speakers, he said, and adjust test results if they are not.

In the end, results may be normal. Or patients have dementia or mild cognitive impairment, a lesser degree of thinking problems that can be a precursor to dementia.

Those who have dementia may undergo further testing to determine whether they have Alzheimer’s disease or some other disorder.

Dementia is a progressive disease, so someone who doesn’t meet the definition now could meet it later. People with symptoms should be re-assessed every six to 12 months, Serruya said. “If they’ve got dementia, there’s no escaping it.”