On Medicare for All and other health plans, candidates should put up or shut up l Opinion

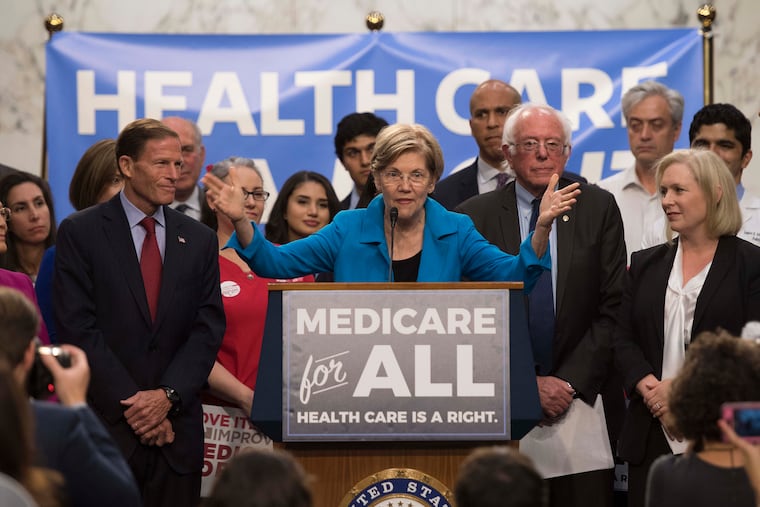

Health care is too important for generalities. Whether you like Elizabeth Warren's plan or not, she deserves credit for being specific.

The figure is mind-boggling: $20.5 trillion over 10 years. That’s how much presidential candidate Elizabeth Warren says her plan will cost above what the federal government currently spends for health care. Cue the attacks.

So here we go again. Another election in which the question of how best to reform the U.S. health-care system will be front and center. Sadly, relying on the media to understand the features of various proposals is like reading a newspaper in a lightning storm — mostly opaque with occasional flashes of illumination.

This piece is not about the relative merits of the various proposals put forth by the presidential candidates. Rather, I want to talk about how we debate health policy and point out the traps set for anyone who proposes a major change. First, a quick discussion about what’s at stake.

Almost one out of every five dollars the U.S. economy generates goes to health care. This is far and above what similarly advanced nations spend, yet U.S. citizens die earlier, are generally sicker, and have poorer outcomes when they get care — and it’s predicted to get worse. Our relatively underfunded public health and social service agencies lack the resources to address the major drivers of disease: social factors such as loneliness, depression, anxiety, systemic inequities, and community conditions. This is American exceptionalism at its worse.

That fifth of the economy is going somewhere. U.S. hospitals and pharmaceuticals are very expensive compared to peer nations. The system is bloated with nonclinical administrative burdens and costs on both the provider and payer sides. Some of this is driven by complex regulations and insurance company requirements designed to improve outcomes and contain costs. The unintended consequence of an evermore burdensome system is clinician burnout and plans for early retirement.

Like an umbrella full of holes on a rainy day, many fully insured families struggle with unaffordable out-of-pocket costs when they get sick. Sad stories abound of parents avoiding huge deductibles and co-pays by parking outside the emergency department hoping and praying their child doesn’t get worse and need to be seen. Even people lucky enough to have employer coverage pay almost a third of the average $20,576 premium for an employer-sponsored family plan. On top of the premium, 28% of covered workers have a deductible over $2,000, which is just an additional fee you pay when you need care. All together, the average family pays over $12,000 a year out of pocket for health care.

These are the challenges for which the presidential candidates are proposing solutions. Warren’s proposal is the most detailed. Her version of Sen. Bernie Sander’s “Medicare for All” would guarantee and expand coverage for all citizens, cover all providers and eliminate out-of-pocket co-pays and deductibles. Her willingness to explain in detail how she would pay for it sets her apart from her competitors.

Not surprisingly, most of the public discussion about her proposal focuses on overall government costs and taxes, not how it would affect families and individuals or how it would affect spending on medical care overall. The individual impact is framed as “losing” your employer coverage, not as what would be gained in exchange. In reality, people lose their health plan all the time when they change jobs, are laid off, or because the boss switches to a different insurance company. The real threat is losing access to your doctors, which happens a lot when insurance companies reconfigure their provider panels. Saturday Night Live brilliantly described an existing health plan as a “bad boyfriend” you’re afraid to break up with. It’s a case of the devil you know.

I can’t say for certain that Warren’s is the right cure for our nation’s ailing health-care system. Maybe, an alternative like allowing people to buy into the existing federal Medicare program — the public option — is better. Perhaps, the answer might be some combination of the two.

Any health-care reform proposal should be judged by objective metrics. Who is covered … and not? How much will people pay out of pocket when they’re healthy or sick? Will businesses benefit from lower costs and a healthier workforce? Will it reward high-quality, cost-effective health-care providers? How disruptive will the transition to the new plan be? These are the issues people care about, not the political noise.

Any politician criticizing Warren’s effort should provide an equally detailed alternative so we can compare them head to head. At this point in our nation’s decades-long health-care debate, we deserve candidates who put up or shut up.

Drew Harris is a member of The Inquirer’s Health Advisory Panel, a health-care consultant and assistant professor at Jefferson University College of Population Health.