COVID-19 vaccine whiz, 35, honored by Franklin Institute for her science and how she communicates it

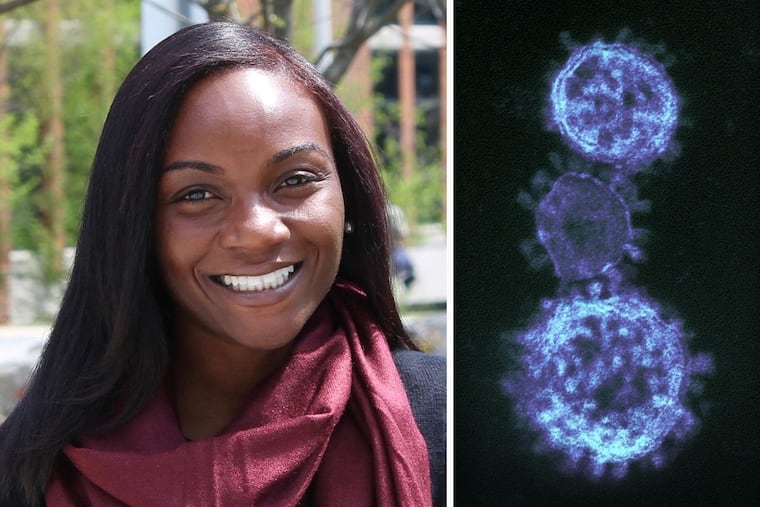

The Franklin Institute announced Thursday that Kizzmekia Corbett, 35, is the winner of a new NextGen award, aimed at recognizing innovation by scientists early in their careers.

Six years before COVID-19, Kizzmekia Corbett already was hard at work trying to stop it.

Two new coronaviruses had jumped from animals to humans since 2002, and Corbett, an immunologist at the National Institutes of Health, wanted to be ready in case of a third. Sure enough, years of dogged groundwork by her and colleagues would prove crucial in producing the vaccines that now have been administered to millions.

The Franklin Institute announced Thursday that Corbett, 35, is the winner of a new NextGen award, aimed at recognizing innovation by scientists early in their careers. She will receive the honor in a virtual ceremony April 29, with an introduction by her boss, NIH infectious-disease chief Anthony S. Fauci.

The museum also is honoring 10 winners of other science and business awards, which were announced last year but not bestowed because the pandemic forced the cancellation of the institute’s usual in-person, black-tie ceremony. Their research spans a variety of timely topics, such as climate change, laser technology, and artificial intelligence.

Yet none is so of the moment as the work by Corbett, who is driven not only by the urgency of the science but by the importance of communicating it.

“If I never talked to anybody in the community, if I never cared whether vaccines got into anyone’s arms, I could still be a very notable scientist,” she said in a phone interview. “But that doesn’t sit right with me.”

So when not poring over data on new virus variants, she speaks to church congregations and other community groups to explain how the vaccines work and why they are safe. Among her converts: Dallas megachurch pastor T.D. Jakes, who had questions about the vaccines at first. But after speaking to Corbett and later hosting a panel that featured her and Fauci, he offered his church as a vaccination site.

“That is really the power of information,” she said.

The Franklin Institute has given awards to scientists and inventors since the 1820s, among them Albert Einstein, Marie and Pierre Curie, and Nikola Tesla. Lately, many recipients have been near the ends of their storied careers — a trend that led to discussions about adding an early-career category at some point.

Given the urgency of the pandemic and the prominent role played by Corbett, this year was the perfect time to put that plan into action, said Darryl N. Williams, the institute’s senior vice president of science and education.

“We’re thrilled that we’re able to recognize the work that Dr. Corbett has done at such a young age,” he said. “We’re really excited to see where the future takes her.”

Fauci also is a fan. When Time magazine included Corbett on its “100 Next” list of emerging leaders in February, he wrote that she “is widely recognized in the immunology community as a rising star.”

A native of rural North Carolina, Corbett excelled at math and science from an early age, always eager to help classmates with their schoolwork.

“Kizzy was always like a little detective,” said her mother, Rhonda Brooks, on the Today show.

She was the first member of her family to attend four-year college, landing a full scholarship to study biology and sociology at University of Maryland Baltimore County. As a Black woman, she was especially drawn in her sociology classes to the topic of health disparities — knowledge that would eventually spur her to study the most effective public-health measure known: vaccines.

Then came a Ph.D at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, followed by the job at NIH. Known for her drive to succeed, with friends calling her “the spreadsheet queen,” she also describes herself as sassy. Her sense of humor comes through on social media, where she praised her grandmother recently for getting vaccinated but chided her for wearing a sweater with the logo of UNC’s hated rival, Duke University.

“Get your grandmas vaccinated, and also, if you pray, send one up to my grandma who is a delusional Duke fan,” she tweeted.

The key discoveries made by Corbett and her teammates involve the coronavirus “spikes” — the proteins that protrude from the surface of each virus particle. Other coronaviruses have them, too, including the ones that cause SARS, which emerged in 2002, and MERS, which was first identified in 2012.

The virus uses these spikes to penetrate cells in human airways, so they were seen as a good target for the vaccines. Teach the immune system to make antibodies that would bind to these spikes, and they would no longer be able to gain entry, or so scientists hoped.

Working with scientists at Dartmouth College, Corbett and NIH colleagues found that the approach did indeed work well in vaccinating lab animals against MERS, particularly if they added two extra amino acids to keep the spike in a stable form.

So when the new coronavirus came along, the NIH team partnered with Moderna Inc. to make a vaccine, urging the biotech firm to use that same approach. Other manufacturers followed suit, all producing spike-based vaccines that proved to be highly effective at preventing severe disease.

The work has taken place at a relentless place, with little of the time scientists usually get to consider alternate approaches or to learn from their mistakes. The first phase of the Moderna vaccine trial began just 66 days after Chinese authorities published the genetic sequence of the coronavirus in January 2020 — an unprecedented turnaround time, made possible in part by the years of NIH groundwork.

“It was like, ‘So what? You got it into a phase 1 clinical trial. Now you’ve got to get it to phase 2,’” Corbett recalled.

And with the need to tweak the vaccines to match emerging virus variants, the pace continues. Yet always, Corbett makes time after work to educate others.

“It’s not part of my job,” she says. “It’s my duty.”

The other Franklin Institute award winners, as previously announced in January 2020, are:

Bower Award for Achievement in Science, Kunihiko Fukushima, Fuzzy Logic Systems Institute

Bower Award for Business Leadership, Arthur D. Levinson, Calico LLC, Apple Inc.

along with the following Franklin Medals in specific disciplines:

Chemistry: Roberto Car, Princeton University, and Michele Parrinello, ETH Zürich and Università della Svizzera Italiana, Istituto Italiana di Tecnologia

Computer and Cognitive Science: Barbara H. Partee, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Earth and Environmental Science: Monica G. Turner, Ph.D., University of Wisconsin-Madison

Life Science: Jeremy Nathans, Johns Hopkins Medical School

Mechanical Engineering: C. Daniel Mote, Jr., University of Maryland, National Academy of Engineering

Physics: Henry C. Kapteyn and Margaret M. Murnane, University of Colorado at Boulder