Divorce after 50 is soaring. Married Swarthmore therapists have a guide for keeping love alive | 5 Questions

According to clinical psychologists Julia Mayer and Barry Jacobs, the so-called “bonus years” of a long marriage offer unique opportunities to deepen a couple's intimacy and emotional connection.

An empty nest. Money woes. Infidelity. Downsizing. Failing health.

A lot can happen to stress marriages as couples grow older.

But, according to clinical psychologists and therapists Julia Mayer and Barry Jacobs, the so-called bonus years of a long marriage also offer unique opportunities to deepen intimacy and emotional connection.

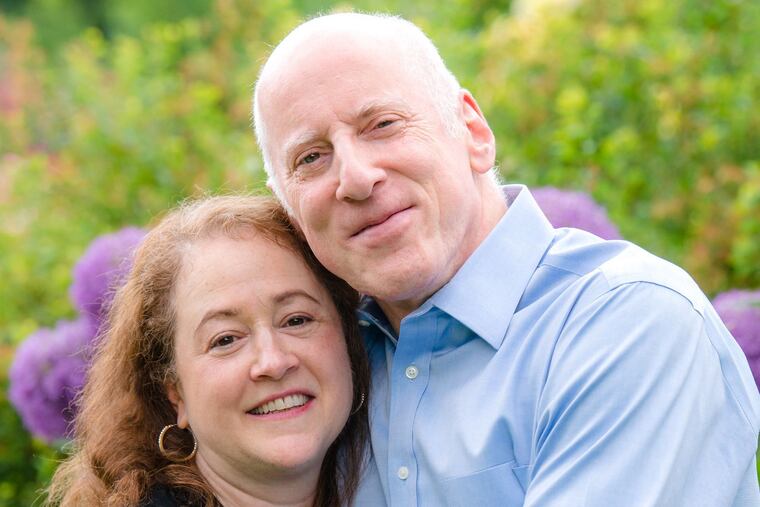

The husband-and-wife team explore this in their book AARP Love and Meaning After 50, a practical survival guide for older couples. Residents of Swarthmore, they have been married for 30 years. They spoke to us recently about their book and the challenges of love after 50.

Why did you focus on this particular age group? What special challenges do they face?

Mayer: A lot of times, when people have been in a long-term relationship, there has been some drift. They’ve been absorbed in child care, their careers, building a nest egg, social climbing. After age 50, things start to shift. People start to consider, when will I retire, will we downsize? The children have left the nest. Often, the couple looks at one another and they have this experience of “who are you?” It’s at that moment that things can get better, or they can get worse. We want couples to take this opportunity, remember why they got together in the first place and build in resilience, make it stronger, plan their future together.

Jacobs: A lot of it stems from our own experiences. Our kids went off to college. We really struggled initially with the empty nest. We realized that our family had been very child-focused, and we had to learn to relate to one another again. We also went through a nine-year period of taking care of parents. It really challenged us as a couple to do what we thought was best for our parents, but also to care for each other.

Tell us about the divorce rate in this age group.

Jacobs: The statistics are not good. They suggest that more and more people are opting out, at a time when the assumption is people are settled in their relationship, they’re content and they’re going to coast to the end. Generally speaking, Americans are living longer. Part of the reason for the phenomenon of gray divorce is when they look down the road and see they have 20 years left, they have more options, including the option to leave. It poses existential questions. What do I care about, and do I care enough about this person to stay with them?

If it’s been a bad marriage, or a lukewarm marriage, they say, “no.” They may also see a person for whom they’ve already made tremendous sacrifices, and they say, “I’d better leave now before I’m stuck with taking care of him later.” They get out early so they don’t have to feel tremendous guilt getting out later.

Mayer: The divorce rate has doubled for people over age 50, and tripled for people over age 65. When we saw those statistics, we thought, “this is really concerning.” There are going to be negative outcomes. Financial strain is a big one, particularly for women. Many have not had careers, and they can’t easily start one at that age. There are potential health outcomes from loneliness.

Another outcome of divorce is the tremendous impact it can have on adult children, extended family and friends. As we get older, we tend to whittle down our circle of friends. By the time someone gets divorced at 65, it’s really hard on the handful of couples they spend time with, or their adult children who are getting married, having children.

Your recommendations — completing a checklist, making an appointment with each other to discuss it, then discussing it again a week later — require a lot of time, effort and honesty. Most people might think that, after decades of marriage, they know each other really well.

Mayer: They may think they know each other really well, but often they are wrong. I have seen in my practice couples who get to retirement age, and one has had a lifelong dream of moving south, and the other has close friends nearby and has no plans to move, and they never even discussed it. People make assumptions about their partners because they think they know them well. People’s wishes and dreams change. Their goals change.

Jacobs: I think people sense that their partner is going to disagree with them, and therefore they avoid that conversation.

Mayer: It can be very scary. The reason we make the checklists with a range of answers – strongly disagree to strongly agree – is that if they’re a few steps apart on the answer, one person strongly agrees, one disagrees, they know they have an issue to discuss. The idea is to really listen to each other and validate the other person’s opinion without judging. People still may not come to an agreement, but if you don’t have the conversation, you’re definitely not going to come to an agreement.

One simple directive you keep repeating is: Listen. Why?

Jacobs: What happens in many couples is that, over time, they can become highly reactive to each other. A certain tone of voice produces a large emotional reaction, even a neurochemical reaction. When people are agitated in that way, they don’t listen well. The other scenario is that people stop listening because they don’t want to react. They nod their head but don’t really listen, not really being curious about what’s going on with the other person. So lots of important issues aren’t discussed, and there’s no emotional connection.

Mayer: It’s almost a dance of communication. During their earlier years, there are so many household tasks, and people often communicate in an almost business-like way. They lose the original communication they had early in their marriage, which is about their experiences and hopes and dreams. It’s easy to talk about who’s going to take out the trash. It’s much harder to talk about my feelings when my mother died. We want couples to honor each other’s feelings and pay attention because that’s how you feel close.

Along more positive lines, what’s good about love after 50?

Mayer: I see this turning point in a long-term relationship where the couple can choose to build, or they can coast, or they can fall apart. What we want for couples is that opportunity to build. In order to do that, couples really need to pay attention to one another in a mindful way. That’s what this book is about. It’s to help couples work their way through challenging conversations they might not even know they need to have.

Every time we make a discovery about our partner, we feel more intimate, we feel closer to the person. If we keep doing that, then what we get is the relationship that we want to have as we grow old together.

Jacobs: The truth is, many people are very happy in these years because they turn toward one another and deepen their relationship. They are not so encumbered by responsibilities. They fall in love again in a different way, more deeply. They cherish one another for their shared history, for their understanding of one another, and they are willing to grow old together. They are willing to face what is to come together.