Tiny eye device could make big difference for millions with blinding disease

Wills Eye Hospital has helped test an implantable delivery system for a widely used medication for age-related macular degeneration.

Melinda Roth feels fortunate. The vision in her left eye went from “a big black blotchy circle” to nearly normal thanks to a drug that stopped the growth of abnormal blood vessels.

But the medication, Lucentis, has to be injected into the eyeball every month by an ophthalmologist. Lessening that drawback has been a goal of researchers ever since the drug debuted 12 years ago — the first treatment to slow age-related macular degeneration (AMD).

Earlier this month, Roth, 59, of Cherry Hill, opted for a wave of the future. An experimental drug delivery device, about the size of a grain of rice, was surgically implanted in her eye at Wills Eye Hospital. Twice a year, the tiny “port” will be refilled with a concentrated version of Lucentis.

“It’s exciting that I don’t have to get shots every month,” said Roth, an online retailer and grandmother. “But it’s also exciting that there’s new medical technology that has had great success.”

The port, being developed by Lucentis’ maker, Genentech, will soon begin the final phase of clinical testing at sites across the country. Researchers hope the results will lead to Food and Drug Administration approval in about three years. Other innovations, including longer-acting drugs and even gene therapy, are also in the research pipeline.

Making treatment less burdensome is not just a matter of comfort or convenience. Studies show AMD patients, many of them elderly, often miss or delay monthly appointments because of illness, transportation problems, or just the unpredictable nature of life. That means many are being undertreated.

“If you’re a week or two late for a visit from time to time, you may have a decline in vision, and you can’t always recover from that,” explained Carl D. Regillo, Wills’ chief of retina service and site leader of the port trial. “It’s a relentlessly progressive disease.”

A leading cause of irreversible blindness, AMD affects as many as 10 million people in the U.S., including two million with visual impairment. The disease damages photoreceptors in the macula, located in the middle of the retina at the back of the eye. The macula is vital to central vision, color, and detail.

No one knows why the cells start to break down. But the early “dry” form of the disease is often associated with yellow deposits, or drusen, that form under the retina. In advanced disease, called wet AMD, abnormal blood vessels multiply, leaking fluid and blood into the macula.

Two approved AMD drugs, Lucentis (ranibizumab) and Eylea (aflibercept, made by Regeneron), work by inhibiting blood-vessel growth. Another growth inhibitor, Avastin, made by Genentech, is often used at doctors’ discretion and has been shown to be as effective. The big difference: Avastin is about $50 per injection, compared with about $2,000 for the approved drugs.

Genentech said pricing for the device and surgery -- and how costs would compare with current treatment -- have not yet been established. The company also said it is investigating “sustained ocular drug delivery” for a number of eye diseases that now require injections.

‘Blacked out the middle’

Five years ago, Roth was diagnosed with dry AMD. She took recommended eye vitamins and (mostly) got annual checkups. But her slowly worsening vision was low priority amid various family crises and a move with her husband from Alabama to Cherry Hill to be closer to relatives.

Almost two years ago, she had a rude awakening. Literally. She woke up and, with her right cheek and eye buried in her pillow, gazed at the alarm clock with her left eye.

“It was like someone took a paintbrush and blacked out the middle,” she recalled.

A South Jersey eye doctor sent her to Wills, where she was diagnosed with wet AMD — and learned about the second phase of the port trial. She enrolled, but was randomly assigned to the comparison group, which got conventional treatment.

Each month, Roth steeled herself to get anesthetic, antiseptic, and a shot of Lucentis in her left eye.

“The injection isn’t painful. But when someone comes at your eye, your natural instinct is to bat them away. You just have to relax and let them come at you,” said Roth, who also usually had a headache or “floaters” in her eye for a day or so after treatment.

When the trial ended in July, she was thrilled to find out she could switch to the port.

Passive diffusion

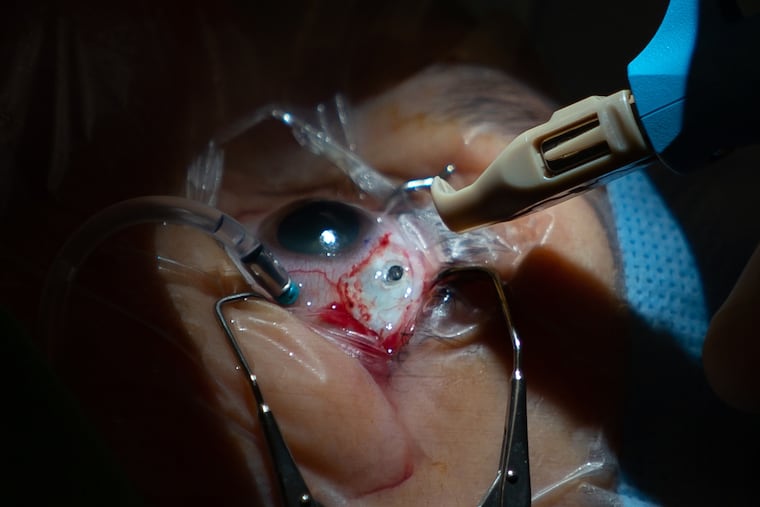

The 45-minute surgery earlier this month unfolded flawlessly, as Roth snoozed under twilight sedation.

Regillo, the retinal surgeon, peered through a scope that magnified Roth’s eye and projected the image on a monitor. Using a blade, he cut and pulled back part of the eye’s protective membrane, the conjunctiva, just above the iris. Then he measured, marked, and cut a tiny pocket – about a tenth of an inch wide and deep – to hold the port device.

After sealing blood vessels in the pocket with a laser, Regillo used a special tool to implant the rice-grain-sized port. The conjunctiva was sewn back in place with four stitches that will gradually dissolve.

The port holds 20 microliters of Lucentis. While that is less than half the volume of an injection, the formula is 10 times more concentrated.

“It works by passive diffusion into the eye,” Regillo explained. “Once it gets into the retina, it’s slowly metabolized.”

Eighty percent of trial participants went six months before needing a refill, done in the office with a special needle that removes any remaining drug and replaces it. Some patients went much longer because, Regillo explained, disease severity and metabolism vary.

Roth’s chances of complications are small. The rates of conjunctiva problems, infection, and retinal detachment in the trial were each less than 2 percent. The risk of hemorrhage in the first month was 4 percent.

Two days after the procedure, Roth was feeling “great.” Her eye appeared bloodshot and the stitches tickled when she blinked. But she couldn’t feel the port, and the top of it was discreetly tucked under her eyelid.

Post-operative 3-D imaging of the inside of her eye reassured her that the itty-bitty implant was in place.

“It’s the coolest thing,” Roth marveled.