This Philly team survived the Final Four — in science

University of Pennsylvania scientists discovered how mice can "sweat" out their fat, taking the top prize in the 64-team STAT Madness.

Though Villanova lost in the semifinals of the NCAA men’s basketball tournament, a Philadelphia team was the champ Sunday in another type of “madness.”

The top prize in STAT Madness, a competition among 64 biomedical research teams, went to University of Pennsylvania scientists who discovered how mice can “sweat” fat molecules. The group hopes its accidental discovery, published in July, could point the way toward a weight-loss treatment for humans.

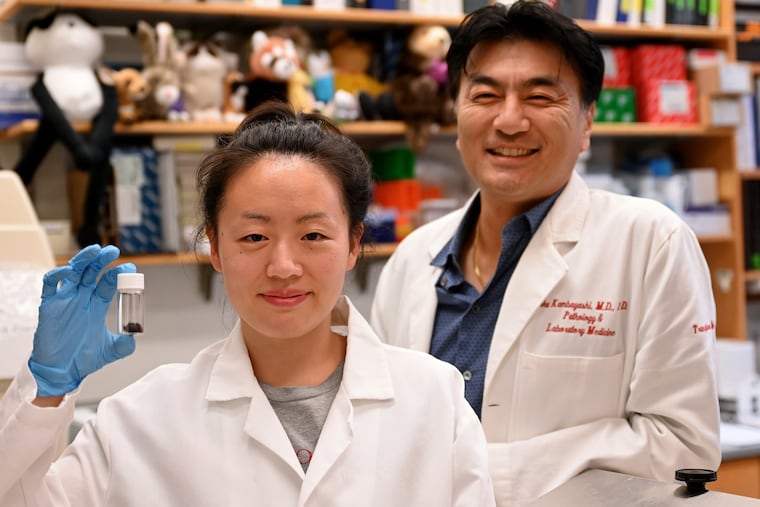

The contest was organized by STAT, a Boston-based media outlet that covers science and medicine. The winning project was led by Taku Kambayashi, an associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine.

The Penn group beat out an entry from the University of California, Davis, in the final round, capturing 71% of the popular vote in the monthlong online contest. The appeal of the paper lay in its weirdness, Kambayashi told STAT.

“I really had fun with it, and it’s very easy for me to convey the information to laypeople,” he said. “When we had this story half-finished, I was talking to more people at the bar than at work.”

» READ MORE: These obese mice lost weight by "sweating" their fat, Penn team finds

The original goal of the research was to explore how certain immune-system cells might be harnessed to treat type 2 diabetes and other complications of obesity.

Kambayashi and graduate student Ruth Choa stimulated these cells in obese mice, and sure enough, the animals’ blood-glucose levels improved.

But to the scientists’ surprise, the mice also lost 40% of their body weight, on average — all in the form of fat.

Additional study revealed that the animals’ weight loss was not the result of burning calories any faster or eating less food. Instead, they were secreting the fatty molecules through their skin.

The secretions were contained in the oily substance called sebum, not sweat. But in talking about his findings, Kambayashi uses the term sweat as a metaphor, to help convey the idea to a general audience.

Some scientists have expressed skepticism that the findings can be applied to people, though humans secrete sebum, too. More study is underway.

The UC Davis contest entry, led by David Olson and Lin Tian, involved the study of psychoplastogens, a family of compounds that includes psychedelics.

It drew lots of positive buzz. But before the voting concluded, Olson had a feeling that the “sweaty” mice would be tough to beat.

“How are we going to be able to compete with that?” Olson told STAT on Saturday. “I think I need to start preparing my concession speech.”