Penn researchers use virtual reality to train bystanders to respond to overdoses

Especially during a pandemic where it’s hard to hold such trainings in person, the study’s authors hope the virtual training can be a more accessible way for people to learn how to reverse overdoses.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania have developed a virtual-reality video that trains people to give overdose victims naloxone, the lifesaving opioid-reversal medicine. And a study the researchers conducted shows the virtual training works as effectively as an in-person session.

Especially during the pandemic, it’s hard to hold in-person training sessions. Plus, drug use remains highly stigmatized. So the study’s authors hope the virtual training can be a more accessible way for people to learn how to reverse overdoses they might observe on a city sidewalk, on the bus, or anywhere else, for a friend or a stranger.

The VR training doesn’t require a high-end VR headset such as the Oculus — just a smartphone and a cardboard headset equipped with special lenses that can be purchased online for less than $10. (The training can also simply be watched, without a headset, on YouTube.)

In the video, a woman slumps to the ground in a cafeteria on Penn’s campus, and onlookers rush to help her. One woman in the cafeteria has naloxone in her purse, and explains the steps of trying to revive someone from an overdose — from CPR-like rescue breaths to ultimately administering a dose of naloxone — before paramedics arrive to treat the woman (and offer more information to viewers).

The video was developed by researchers at several departments at the university, including the School of Nursing and the Annenberg School for Communication, and is geared toward laypeople, not health-care professionals. It was tested at nine libraries around Philadelphia during naloxone giveaway days in 2019 and early 2020.

According to the study, published this month in Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 94 people participated in either a virtual training or an in-person training; those who took the virtual training improved their knowledge on reversing overdoses as much as those who took the in-person training.

“[The VR] training stands alongside getting the in-person training — what we really needed to know was that this wouldn’t be performing worse,” said Natalie Herbert, the lead author on the study, who earned a Ph.D. at Penn’s Annenberg School this year and is now a postdoctoral fellow at Stanford University.

Herbert and her coauthors had been inspired by the virtual-reality training sessions that Penn uses with its nursing students. Because opioid overdoses often happen outside of clinical settings, on the street or in a private home, the researchers brainstormed ways to use VR to educate the wider public.

“There’s definitely that mentality of virtual reality not being a common asset for people, but in reality, even with the most basic equipment, this can be really impactful,” said Nick Giordano, a former lecturer at the Penn School of Nursing and an assistant professor at Emory University.

The researchers have received a grant from Independence Blue Cross to disseminate the training, which is free and available online. They’re hoping to continue to partner with city libraries to train more people to use naloxone. “Further down the road,” Giordano said, “we’re hoping that people can request [VR] headsets from us, and we’ll be able to disseminate this through the mail.”

He said he had been struck by the training’s potential and recalled a woman at a naloxone giveaway event near Penn’s campus last winter who asked whether she could take the VR training.

“She said, ’I just lost my daughter to an overdose, and I really, really wish I knew what I could have done better,’” Giordano said. “She just lost someone, and the only thing she could think about was ’Did I do enough?’ It said so much to us about where we could go with this work.”

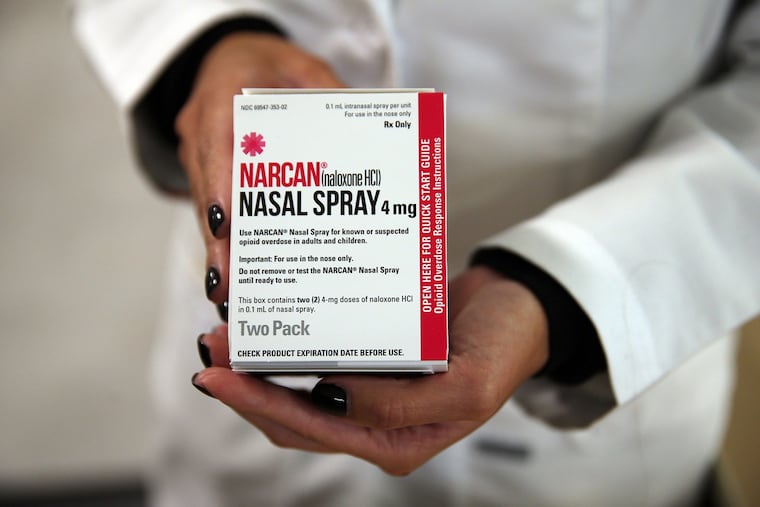

Naloxone is available at any pharmacy and does not require a prescription; most insurance covers it with a co-pay of $20 to $40. Doses of naloxone are also available for people who use drugs and those directly connected to them, through a mailing program run by the addiction outreach and activism group SOL Collective and Next Naloxone. Visit naloxoneforall.org/philly, watch a short training video, and enter your address to receive a dose.