Temple University Hospital is being investigated by CMS over its care of a homeless patient who died

Staffers turned away a patient from the emergency department without evaluating him to determine if he was stable. Experts say the hospital’s actions amounted to “patient dumping."

A patient with no home to return to was pushed in a wheelchair to the curb outside Temple University Hospital. Staffers left him sitting on a bench, even though he was considered at a high risk of falling.

An hour later, a security officer found the man had fallen and was lying on the ground.

He was shaking when the guard brought him back into the hospital, but didn’t respond to a nurse’s questions. So hospital staff again sent him away — this time leaving him alone in a wheelchair outside the emergency department.

He was found there five hours later, slumped over, unresponsive, and without a pulse. He died the following week.

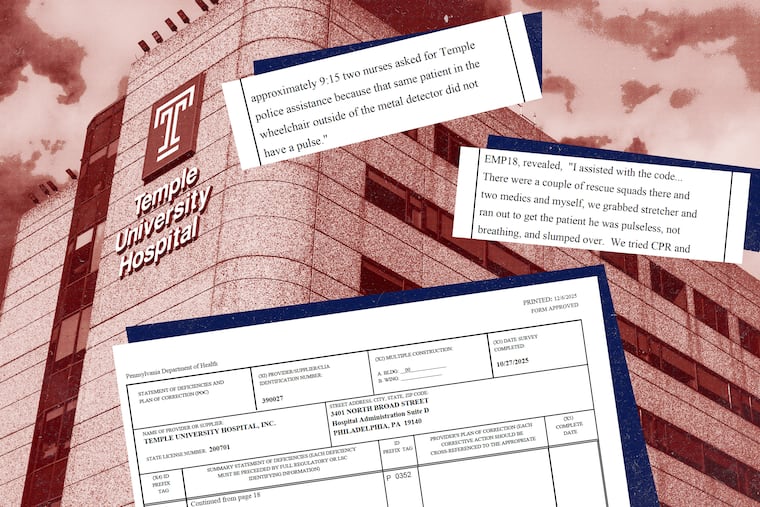

Temple’s treatment of the patient during the Oct. 3 incident prompted state and federal investigations. In a report released earlier this month, the Pennsylvania Department of Health cited Temple for violating state rules that require hospitals to provide emergency care.

Experts say the hospital’s actions amounted to “patient dumping,” a practice prohibited under a federal law that requires hospital emergency departments to medically screen and stabilize all patients.

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), which oversees hospital safety nationally, confirmed it is also investigating, but has not released details.

Hospitals that violate the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, known as EMTALA, risk hefty fines or losing their Medicare license, though such penalties are rare.

Temple acknowledged that its own protocols were not followed. Health system officials told state investigators the patient should not have been removed from the hospital without being evaluated and cleared by medical staff.

“The safety of our patients, visitors and staff is Temple’s highest priority,” the hospital said in a statement to The Inquirer. “We believe that everyone deserves high quality care.”

The hospital declined to say whether any of the staff members involved were disciplined or fired.

But such incidents are rarely the fault of one individual, legal experts and homelessness advocates said. Rather, they are a sign of systemic problems, such as understaffing that can leave staff overwhelmed, and bias among medical providers that can put vulnerable patients at risk of being dismissed.

“If you work in an environment where safety is prized and honored and enforced from the top down, everyone feels that’s their mission,” said Eric Weitz, a medical negligence lawyer in Philadelphia. “If that’s not a priority being set by leadership, then it’s no surprise the culture doesn’t reinforce it.”

Hospital administrators said the triage nurse who turned away the patient should have sought help, if the patient wasn’t responding to questions. The nurse said she was overwhelmed and working without sufficient support in one of the region’s busiest trauma hospitals.

“I was busy and alone,” she told state inspectors.

Pa. Department of Health investigates Temple

To piece together what went wrong, Pennsylvania Department of Health inspectors watched security camera footage, interviewed staff members, and reviewed internal hospital reports. Their timeline shows a series of mistakes.

At about 3:15 p.m., an employee brought the patient in a wheelchair to a bench near the curb outside the hospital, and left him there on the mild October day with highs near 70 degrees.

He was being discharged to “the community” because he was experiencing homelessness, according to the inspection report. (The state report does not say whether staff attempted to place him at a skilled nursing facility, rehabilitation center or homeless shelter.)

The man sat alone on the bench for an hour before standing unsteadily, taking a few steps, and ultimately falling to the ground.

He managed to get back up, leaning against a tree for support, only to fall again. He was on the ground for 10 minutes before a security guard found him.

The guard brought the man back into the emergency department in a wheelchair about two hours after he had been released.

Back inside the hospital, the man followed orders to raise his arms for a security check at the door. Then he waited in line to be seen by the triage nurse responsible for checking in patients at the emergency department.

When he reached the front of the line, he did not respond to the nurse’s questions. “He was not answering any questions, just shaking,” according to a Temple incident report reviewed by inspectors. Staff said the patient was “not cooperating” and should be sent to the back of the line.

After two minutes with the nurse, a security guard moved his wheelchair to a corner of the emergency department near the entrance.

The man was once again wheeled outside the hospital a few minutes later and left alone.

He was found by medical staff around 9:30 p.m., slumped over in his wheelchair.

Staff began CPR, rushing him back inside for trauma care.

The inspection report does not identify the patient’s name, age, or provide details on the medical condition for which he had been hospitalized. It also does not say what happened after he was found unresponsive. He died five days later, on Oct. 8.

Temple responds

Medical screening of every patient who comes to the emergency department is “explicitly required” under Temple’s EMTALA policies, according to the hospital’s response to the state findings.

“It doesn’t matter if they were just there an hour ago, every time they present, it is a new encounter and should be documented as such,” a Temple staffer said in an interview with inspectors.

The hospital told the state it would retrain staff on EMTALA rules, making clear that security officers cannot remove patients from the emergency department unless they have been evaluated and cleared for release by a medical professional.

A week after the incident, hospital staff were instructed to keep a log of patients who are removed from the emergency department and the name of the provider who approved their release. (Temple police may still remove patients from the emergency department if they are threatening the safety of other patients or staff.)

The hospital also said that it would order mobility evaluations for patients who are being discharged “to the community” if they had a high risk of falling, with a doctor’s sign-off required.

Temple treats some of Philadelphia’s most vulnerable patients in an emergency room that sees more than 150,000 visits a year, including high numbers of gunshot victims and people experiencing opioid withdrawal. It operates a Level I trauma center in a North Philadelphia community where 87% of patients are covered by publicly funded Medicare or Medicaid.

The emergency department is so busy that about 8% of patients choose to leave before being seen, according to CMS data, compared to about 2% of patients at hospitals nationally and across Pennsylvania.

The triage nurse on duty Oct. 3 is not identified in the inspection report.

The Temple chapter of Pennsylvania Association of Staff Nurses and Allied Professionals, which represents 1,600 nurses and 1,000 other medical professionals on Temple campuses, declined to comment.

» READ MORE: A Virtua Voorhees nurse reported a baby-switch mistake. Then she was fired.

Legal experts raise questions

Two healthcare lawyers who reviewed the state’s inspection report said the entire episode is troubling.

“It sounds like they violated every part of EMTALA,” said Sara Rosenbaum, professor emerita of health law policy at George Washington University.

The law does not require specific treatment, but mandates that hospitals evaluate everyone who walks in the door seeking care, and prohibits them from sending them away or transferring them until they are medically stable.

“They failed to screen him, threw an unstable person back on the street, and didn’t arrange a medically appropriate transfer,” she said.

What’s more, the hospital could be sued for malpractice over how it initially discharged the patient.

The incident appears to be “a classic EMTALA violation,” said Weitz, the Philadelphia lawyer who serves on Pennsylvania’s Patient Safety Authority, an independent state agency that monitors hospital errors.

The health department’s description of what happened is “almost eerily the exact fact pattern the law was passed to prevent,” he said.

Healthcare challenges for patients experiencing homelessness

People who are experiencing homelessness often receive subpar treatment when they seek medical care, research shows.

One study that analyzed thousands of California patient records found that those who were described in their medical records as “homeless” were more likely than patients who have a permanent legal address to be discharged from the emergency department, rather than being admitted for care.

In the Philadelphia region, caring for this population is increasingly challenging. The number of available shelter beds has declined in recent years, while the number of people who are considered unhoused has risen, according to Philadelphia’s Office of Homeless Services.

Stephanie Sena, CEO of Breaking Bread Community Shelter in Delaware County, said the colder months also see more people experiencing homelessness coming to hospitals to get off the street.

“If they say they’re sick, they might get a bed and be able to survive the night,” Sena said.

The pattern can make doctors and nurses less likely to believe patients when they report real medical needs. Especially when staff are overwhelmed in busy hospitals, patients experiencing homelessness may be at greater risk of getting denied or discharged when they need help, she said.

Sena said she was disappointed to hear about the Temple incident.

“It is tragic,” she said, “but also not at all surprising, unfortunately.”