FDA approves a second drug to boost libido in women

Drug companies have long lusted to find a "female Viagra." Will Vyleesi be it?

A drug that grew out of a search for a sunless tanning agent won U.S. approval Friday as the second medication to treat premenopausal women who are troubled by a lack of sex drive.

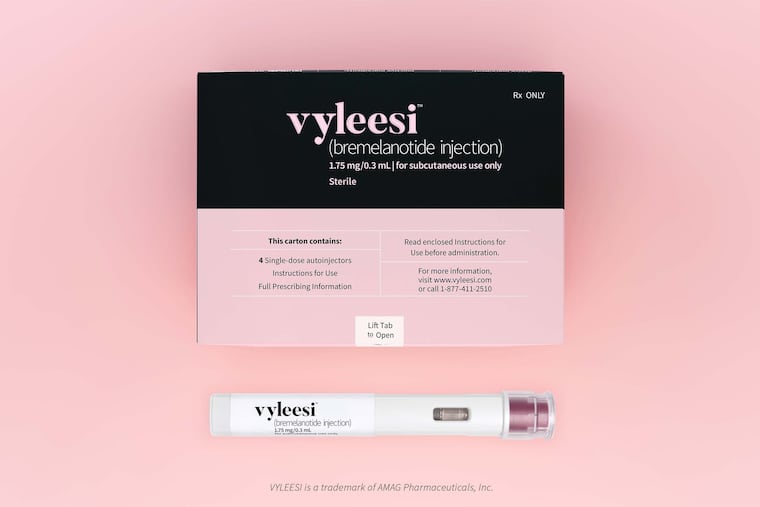

Bremalanotide, to be marketed by Amag Pharmaceuticals as Vyleesi, comes in an auto-injector pen that women would use about 45 minutes before they plan to have sex.

"There are women who, for no known reason, have reduced sexual desire that causes marked distress, and who can benefit from safe and effective pharmacologic treatment. Today’s approval provides women with another treatment option,” U.S. Food and Drug Administration official Hylton V. Joffe said in a statement late Friday afternoon.

Drug companies have been pursuing pharmaceutical fixes for female sexual dysfunction ever since Viagra’s blockbuster debut for men two decades ago. But female sexual dysfunction has proved far more difficult to define and diagnose, much less treat, than erectile dysfunction. A score of drugs that reached late-stage testing have been abandoned or repurposed. And Addyi, Sprout Pharmaceutical’s once-a-day pill, hasn’t caught on four years after its controversial approval as the first drug for low libido, technically called hypoactive sexual desire disorder (HSDD).

Julie Krop, chief medical officer of Amag in Waltham, Mass., said Vyleesi’s approval "underscores Amag’s commitment to raising awareness and improving education about HSDD.”

In an interview before the approval, she said, “We’re just excited to get this drug to women. [HSDD] has been stigmatized, and people haven’t known it’s a treatable condition. I think it will be such a relief to women suffering from this condition that there is something physiological they can treat.”

Some sex therapists say that message is marketing, not reality.

“Female sexuality is so complex,” said Lawrence Siegel, a sex therapist and certified sex educator in Boynton Beach, Fla. “If a guy gets an erection, he’s good to go even if he’s not into it. The benefit this drug will bring to a small number of women is still going to have to exist in the context of sex therapy. This can’t be a stand-alone treatment.”

“There are a lot of things that contribute to low sexual desire. For example, many women have dealt with sexual trauma,” said Christian Jordal, a family and sex therapist at Drexel University. “Although this particular drug has shown some promise, I think there’s a larger discussion about whether this is the medicalization of women’s sexual desire.”

HSDD is estimated to affect 10 percent of premenopausal women, and many more after menopause. By definition, the condition must bother the woman. (Drug companies used to claim 43 percent of women ages 18 to 59 were sexually dysfunctional, citing a vaguely worded 1999 survey that didn’t ask about distress.)

Both Addyi and Vyleesi work by altering brain chemistry, but exactly how is not clear.

Vyleesi activates melanocortin receptors, which are involved in producing skin-darkening pigmentation. Indeed, bremalanotide is based on a compound that was first tested in the 1960s as a potential tanning product. That early compound also caused a sexual response in rats, and triggered a persistent erection when a researcher injected himself.

In clinical trials of Vyleesi, about 1 percent of patients reported darkening of the gums and areas of the skin, including the face and breast — and in half of them it persisted after treatment stopped, the FDA said. Vyleesi caused nausea in 40 percent of patients, including 13 percent who needed nausea medication. Flushing and headache also were common.

Like all drugs tested for female sexual dysfunction, Vyleesi helped some women — but so did a placebo. The FDA’s decision was based on a pair of 24-week-long clinical trials involving about 1,200 women. A quarter of patients on Vyleesi had self-reported improvements in desire, compared with 17 percent on placebo. Vyleesi reduced distress in 35 percent, compared with 31 percent on placebo.

Cindy Pearson, executive director of the National Women’s Health Network, an education and advocacy organization, faulted the FDA’s approval.

“Women don’t have enough information to make an informed decision about whether it’s safe and effective,” she said. “I’m sad to say this, but right now, women can’t trust the FDA to say no to a bad drug. The FDA set the bar too low when it approved flibanserin. Have they lowered it even further with bremalanotide?”

Addyi, chemically called flibanserin, was twice rejected by the FDA because of concerns about marginal benefits vs. serious risks. It was finally approved, but with tough warnings against alcohol consumption, which can trigger low blood pressure and fainting. The FDA recently eased that precaution, saying women can drink two hours before taking Addyi and the morning after a bedtime dose. Sprout also slashed the price of its product -- originally $800 a month -- and now promises “no more than $99 a month out of pocket.”

Amag did not disclose Vyleesi’s price tag, but said it was working to get health insurance coverage when the drug becomes available “through specialty pharmacies” in September.

Amag and Sprout have been using websites and social media to build awareness of HSDD. Amag’s campaign is called unblush.com, while Sprout’s is righttodesire.com. Such unbranded “disease awareness” efforts have been praised for bringing taboo subjects into the open but also decried by critics as “disease-mongering.”