Longtime Roman Catholic High coach Billy Markward to be nominated again for Basketball Hall of Fame

Former St. Joseph's athletic director Don DiJulia cited Markward's "early contact with women and African-Americans and because of the establishment of the Markward Club."

For several years now, a handful of Philadelphians have confronted a basketball challenge every bit as confounding as the NBA’s salary cap:

How do you get the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame -- an exclusive institution populated by some of the most colorful and charismatic figures in sports history -- to select a man who resembled a dyspeptic accountant, averaged 2.6 points as a 6-foot, 180-pound pro, never coached above the high-school level, and died 71 years ago?

Next month, for a fourth straight year, Roman Catholic alum Joe Kiernan; the Rev. Joseph Bongard, Roman’s president; and former St. Joseph’s University athletic director Don DiJulia will nominate William “Billy” Markward for the hall, whose Class of 2020 will be revealed during the NCAA’s Final Four in April.

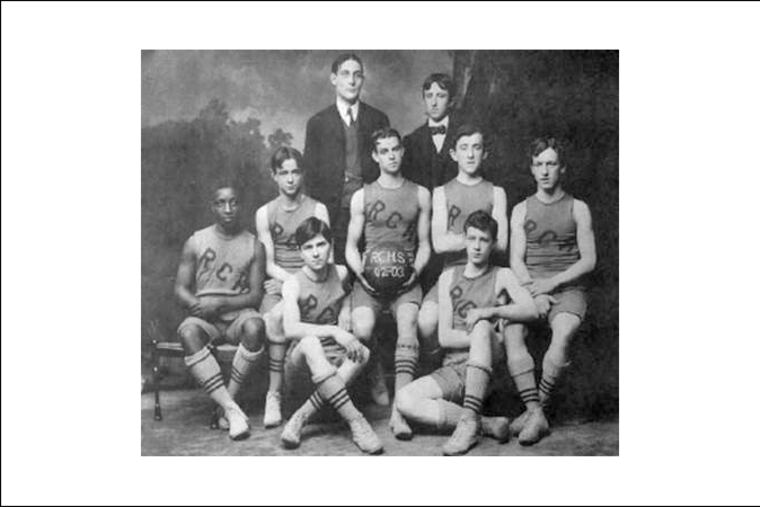

There are no films of Markward’s Roman Catholic teams to help the coach’s case. In still images, his Cahillites — floor-bound young men in knee pads and skimpy satin shorts — seem to be playing an alien sport. Photos of Markward himself, meanwhile, are equally unimpressive, revealing an overweight, bespectacled, pallid, often unsmiling coach.

According to his supporters, the reasons he deserves to be enshrined in Springfield, Mass., lie below the surface.

“There have been a lot of successful coaches around the world, so he might not distinguish himself there,” DiJulia acknowledged. “But because of his early contact with women and African-Americans and because of the establishment of the Markward Club, which was unprecedented and still is doing so much today in his name, we think he’s a unique case.”

The push for Markward has been supported by both Roman Catholic and St. Joseph’s, where many of the coach’s charges played collegiately. It began in 2015, not long after Markward was inducted into the Philadelphia Sports Hall of Fame.

“There was a lot of talk about him, and people started urging me to try to get him considered for the Basketball Hall,” Kiernan said.

Kiernan and a daughter, Mary Boyle, created an information packet highlighting Markward’s career and submitted it before the 2016 vote. This time, under the hall’s arcane election procedures, he will be considered as a Veteran, someone who’s been retired 35 years or more, and not in the broader category of Contributor.

Basketball pioneer

Markward died in 1947 at age 68. While his name remains one of those that drifts through the rich atmosphere of Philadelphia basketball, there are few who know why.

“The Markward Club has kept his name alive,” said Kiernan, who was a Roman student at the end of the coach’s tenure there. “But there aren’t many who know the details. There really aren’t many details out there.”

Born in Philadelphia in 1878, Markward was a basketball pioneer. He participated in the young sport’s black-and-blue era, playing in the caged gyms of city churches and athletic clubs. He coached Roman for 41 years and won 20 league championships, earned a national reputation, and rejected several college offers. He was a groundbreaking advocate for women and African-Americans in the young sport.

But what DiJulia believes sets him apart is the Markward Memorial Basketball Club, an organization founded in his honor in 1947 that, through its weekly award luncheons, has supported and enhanced high school and college basketball in the Philadelphia area.

Legendary St. Joseph’s coach Jack Ramsay, a Hall member who employed many of Markward’s techniques, called the club “the headquarters of scholastic and college basketball in Philadelphia.” Among the thousands it has honored were future Hall of Famers such as Wilt Chamberlain, Guy Rodgers, and Tom Gola.

“No such organization exists elsewhere in the nation,” Kiernan wrote in his self-published 2015 Markward biography, Billy Markward and Friends. “It is uniquely and proudly Philadelphian.”

And so was Markward. A decorated Spanish-American War veteran who grew up in the Devil’s Pocket neighborhood between Center City and South Philadelphia, he discovered basketball soon after its 1891 invention.

“In those days, they kept basketball players and black panthers in cages — for roughly the same reasons,” said famed columnist Red Smith, who despite a distaste for basketball frequently wrote of Markward.

A physical 6-footer, he was tough enough to play professionally (1900-07) with teams in Philadelphia, Wilmington, and Camden. But Markward, who never went to college and worked as a laborer, a roofer, and a city clerk, also appreciated the mental aspects of the game.

Soon, he was teaching the new sport to youngsters in high schools and clubs. His disciplined theories, especially the passing system he devised, helped tame a brutal sport.

Though an Episcopalian, Markward was hired as Roman Catholic’s coach in 1901. He stayed at Broad and Vine until 1941. Among his players there were Matt Guokas Sr.; Bill Ferguson, who later coached St. Joseph’s for 25 years; future Eagles general manager Vince McNally; and Joseph Breen, who would one day wield tremendous power as Hollywood’s chief censor.

Sportswriters called Markward “the Knute Rockne of high school basketball.” The Inquirer characterized his teams as “sheer, satiny basketball machines.”

When Markward retired, Smith wrote that “it didn’t help the other team to know his signals any more than it ever helped a batter to steal a fastball sign from Walter Johnson’s catcher. They couldn’t hit the hard one. They couldn’t stop Markward’s plays.”

Joe Driscoll, who played on Markward’s last team and spoke when his old coach was elected to Philadelphia’s Sports Hall of Fame in 2015, said he was “totally systematic, knowing exactly what he wanted and how to teach it.”

Philadelphia’s first integrated team

One of Markward’s earliest Roman teams, in 1902, was also Philadelphia’s first integrated high school hoops squad. Before that season began, the Interscholastic League — the Catholic League wouldn’t be formed until 1920 — informed Markward that his club couldn’t compete as long as Johnny Lee, the black son of former slaves, was on its roster.

Instead of complying, as many others did in that segregated era, the coach had his players vote on how to proceed. After they unanimously decided they wouldn’t take the court without Lee, the league backed down.

According to Kiernan, the incident “has been cited as a significant moral precedent that helped inform the tone of racial equality in Philadelphia scholastic sports.”

Then in 1925, when Philadelphia hosted the women’s national championships, the Scott-Powell Milkmaids asked Markward to be their coach. Though he was the city’s leading basketball figure at a time when women’s sports were decidedly second class, Markward accepted. That spring, in what The Inquirer described as a “big ballyhooed contest” at Shanahan Hall, 47th and Wyalusing, his team captured the title.

Through the years, several colleges, including St. Joe’s, Penn, Princeton, and Yale, sought him. He turned them all down.

“Why should I stick my neck out by accepting a college post?” he said in 1925. “Here at school, everyone is pleased if we win, but losing is not a sin.”