Remembering Lewis Lloyd, a Philly hoops legend

The former NBA player died on Friday at age 60.

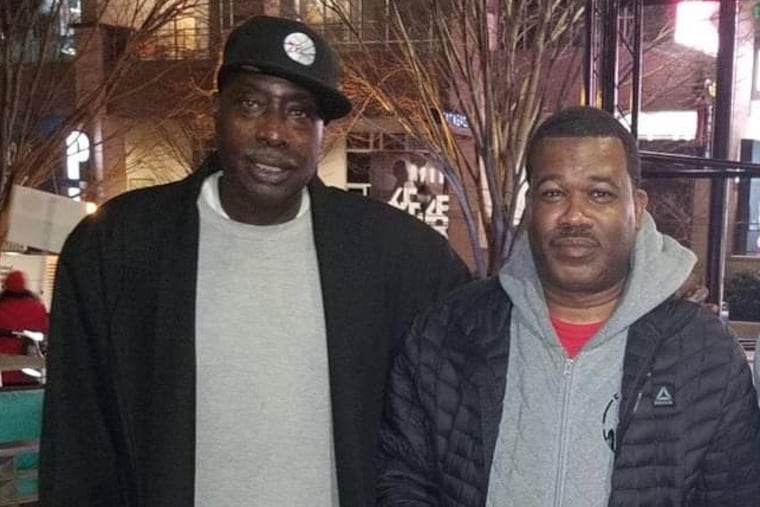

Before the 2015 NBA All-Star Game in New York, Littel Vaughn, a walking, talking encyclopedia of Philadelphia hoops, was inside a hotel in Manhattan when he heard a commotion from behind. He looked back and saw Gary Payton. People were excited to see Payton.

Payton was excited about seeing someone else.

“Lew was behind him," Vaughn said.

It tells you more than a little about the basketball stature of Lewis Lloyd, who died Friday at age 60, how Payton, a nine-time NBA All-Star, once reacted to seeing him.

“What’s up, Glove?" Lloyd said to Payton from behind.

In Vaughn’s memory, Payton didn’t recognize the voice, but turned back.

“Gary’s kind of an animated guy," Vaughn said. “He turned around and started screaming. He put his face close to Lew. He turned to the people he was with, said, ‘You know who this? I was a young boy, but I’m telling you, this man was bad!’ ‘’

Payton later explained to Vaughn how growing up in Oakland, he watched Lloyd break in with the Warriors, doing things he hadn’t seen before on a basketball court, and also show up at a random summer league in the Bay Area and annihilate professionals.

Nobody in Philadelphia would have argued. Battles between Lloyd’s Overbrook team and Gene Banks from West Philadelphia High are part of this city’s basketball history.

“The greatest playground dude in Philly -- there’s so many," said Vaughn, who ran summer leagues and put out Checkball magazine, all about Philly hoops. “Who did it the longest and best, and translated it to the NBA, was Lewis Lloyd.”

He also had a history that included being suspended by the NBA for drug use, and that use apparently continued. James Garrow, spokesman for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health, said Tuesday that the medical examiner’s office had determined Lloyd’s death was “accidental from drug intoxication.” No other details would be revealed publicly. The cause of death was first reported Tuesday by the Philadelphia Tribune.

Vaughn grew close to Lloyd after the player had finished his NBA career.

“As a person, he had a heart of gold," Vaughn said. “A lot of NBA guys, they make millions, it’s like they do camps more for PR. He’d do camps when he barely had anything. He was never selfish. Later on, he would share his contacts, his mistakes, his failures, his good points. He would share.”

Some give Lloyd credit for actually inventing the Eurostep move now in vogue. Vaughn is a basketball historian, though. He’s seen film of Elgin Baylor doing similar moves a decade or two earlier.

“Lewis Lloyd perfected it," Vaughn said. “He added something to it. He lifted one leg.”

Lloyd would always want everybody to be together instead of bickering, Vaughn said. “At All-Star Games, all these legends, they would run up to Lew like Lew was a Hall of Famer, which he had the talent to be.”

It was demons off the court that kept that from happening. Lloyd had played two seasons at Drake, averaging 30.2 points as a junior and 26.3 points as a senior. In his best NBA season, Lloyd averaged 17.8 points a game for Houston in 1983-84. As a pro, he scored 5,130 points and had 1,192 rebounds. He was suspended from the NBA in 1986 for testing positive for cocaine.

“The only problem with Lew, because of his situation, his demons -- to be a featured player in the NBA, you had to stay focused the whole game," Vaughn said.

Did Lloyd ever talk about that?

“The only thing he said, if he had the freedom to get all his shots, he would get 25 a game," Vaughn said.

The game has changed. Now, maybe Lloyd in his prime would get all his shots. Vaughn said a former Houston scout would tell him about how at practice Lloyd was unstoppable. Except his own coach would slow him a bit, tell him to get the ball inside. Since the guys inside were Hakeem Olajuwon and Ralph Sampson, this made sense.

“George Gervin called me on Friday," Vaughn said. “Gervin was saying a lot of young guys in the ’80s were scared of [Gervin].”

The Iceman had earned that status in San Antonio.

“That dude wasn’t," Gervin said of Lloyd. “We had rivalries.”

Maybe Lloyd most lived up to his Black Magic nickname in the summer.

“His style of play, his charisma, his flair," Vaughn said. "Also, he had that smile.”

Vaughn didn’t go back as far as the late ’70s to the high school battles with Banks. But he does remember going to a Baker League All-Star Game when Earl Monroe, already retired from the NBA, threw an alley-oop to Lloyd.

“It was like passing the torch," Vaughn said.

Or Lloyd going against Charles Barkley in the Baker League early in Barkley’s 76ers time.

“He was the best player in the city, but not that night," Vaughn said of Barkley. “Lew would kill -- I wouldn’t say kill, but he would outplay him.” Vaughn relayed how Barkley wanted the Sixers to pick up Lloyd to take some offensive pressure off him. They eventually did, just on a 10-day contract in 1990, Lloyd’s final year in the league, but they didn’t keep him beyond the 10 days. His skills weren’t translating to the NBA by the end.

“People don’t know, Lewis has the all-time NBA field goal percentage for a two guard, that’s a fact," Vaughn said. “He was efficient, had a mid-range game, would be dunking.”

Depending on how you define different players by position, Lloyd’s 52.4 percentage holds up. But it wasn’t his numbers that will be remembered, more how he accumulated them.

“To me, he’s top five," Vaughn said of Lloyd’s place in the pantheon of players from the city. “Just in terms of talent.”

Lloyd once told Vaughn that Bernard King, whom Lloyd had backed up as a rookie when both were with the Warriors, was the most talented offensive player he ever faced.

“Don’t get it messed up," Vaughn remembers Lloyd adding. “He couldn’t stop me either.”