He’s back, cool cats! WRTI jazz DJ Bob Perkins returns to the airwaves after a stroke

"People say, ‘You ought to give it up, man, go retire somewhere.’ Why? I’m the only one that’s doing this thing on regular radio, and I enjoy very much what I’m doing, and the feedback that I get from people who enjoy it. Maybe it’s one of the high points in their life."

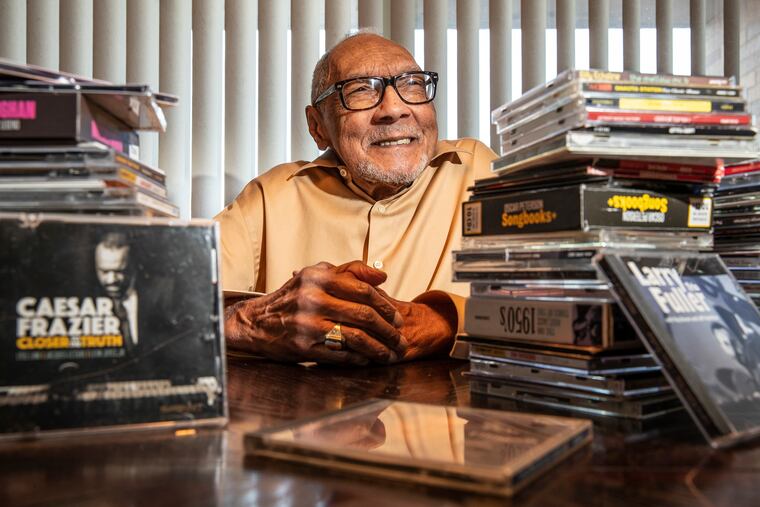

Growing up in a two-bedroom rowhouse near 19th and Reed in South Philly during World War II, Bob Perkins received intimate and powerful instruction on the healing properties of radio.

“My dad was my radio school,” the 86-year-old remembered. “He fell ill around 1940 with rheumatoid arthritis,” and was forced to leave his job as an elevator operator. “He loved radio programming, and since I was the last kid at home, we listened together to all the great voices — John Facenda and Edward R. Murrow — anything that was on the radio, from Jack Benny to the Philadelphia Athletics games. I knew the Athletics’ batting averages like they were my own name.

"I got radio rammed down my throat, because that was my father’s relief from his pain.”

Perkins sat and listened and learned his lessons and developed a calling. For 50 years he has been one of the great voices of Philadelphia radio, starting in 1969 with a nearly 20-year stint as a news and editorial reader for WDAS, known in those days as The Voice of the Black Community.

“I did what I could,” he said, “because I didn’t know a thing about writing editorials. But I mimicked what I thought the great guys I’d grown up with would do, and I got away with it for years.”

» READ MORE: Talking all that jazz with WRTI legend Bob Perkins

His older brother had introduced him to the music of Duke Ellington, which sparked a lifelong love of big band and jazz music. He wanted to share his obsession. Not quite content as a newsman, in the late ‘70s he volunteered for a moonlighting job as a weekend music DJ with WHYY, where he coined his on-air moniker: “BP with the GM” — Bob Perkins with the Good Music.

“That when I first became aware of who he was,” said Larry McKenna, the tenor saxophonist who is one of the deans of Philly’s jazz scene. “The thing I liked about what Bob did was that he didn’t call it a jazz show. He’d just play people that he liked. On this show he would play a record by Dick Haymes or Doris Day or Rosemary Clooney. But then he’d also play Miles Davis, Maynard Ferguson, John Coltrane, and Bird.” (The last being the nickname for the brilliant bebop jazz saxophonist Charlie Parker.)

“I remember telling my friends about it,” McKenna adds. “You should hear this guy.”

When WHYY dropped its music programming to concentrate on news and information, Perkins moved uptown. Over the last 20-some years, BP with the GM has become an icon of the Philadelphia airwaves, holding down a prime, three-hour early evening time slot Monday through Thursday on WRTI. The station, run by Temple University, plays classical music during the day and transforms in the evenings into one the country’s premier jazz music broadcasters. He throws in a four-hour show on Sunday mornings for good measure.

One day in late summer last year, his familiar and congenial voice — the aural equivalent of a cup of hot chocolate and a soft blanket — went silent.

» READ MORE: Two Philly jazz masters celebrate their birthdays (and their best-friendship)

Perkins had suffered a stroke. “Since I turned 65,” he reports with a tone more of irony than self-pity, “it’s been one thing after another. But what are you going to do? My gerontologist tells me, ‘Keep moving.’”

Maureen Malloy, the director of jazz programming at WRTI, says there was “an insane amount” of listener response to Perkins’ unexplained absence. “We weren’t sure at first when he’d be back, so we didn’t say anything.” Finally, in mid-November, a post went up on the WRTI web page. It was typically BP in tone.

“I’ve got high mileage on my odometer,” Perkins wrote. “BP and ‘Father Time’ have been having a continuous battle over the last several years and I’m trying not to let him win the battle! I’m waiting for my doc to give me clearance to return to work so that I can keep putting out that good GM …. I look forward to you lending me your finely tuned ears very soon."

BP brought the GM back for the first time in more than four months — his longest absence from the Philadelphia airwaves in 50 years — on a Thursday night in December, followed a few days later by his Sunday show at 9 a.m.

What he will bring to the microphone in a neat control room on Cecil B. Moore Boulevard just west of Broad Street is something his colleague Bob Craig describes as “a style that is very, very warm and very personal and very loose."

“BP going one on one with the audience shows a very strong kinship,” said Craig, himself a 40-year veteran of local radio. “He’s speaking their language — especially people who have been listening for years and years.”

In this new age of music streaming, where a service like Spotify uses neural networks, big data language analysis, and artificial intelligence machine learning techniques to winnow songs that are channeled down a high-tech digital assembly line to listeners, Perkins relies on a soft, squishy computer that he admits is a bit more unreliable since his stroke and which he refers to in his characteristic parlance as “the old noggin.” In other words, he plays what he knows and likes. He is one of the few DJs at WRTI, or any radio station in existence nowadays, allowed such a luxury.

“I program most of the music on the station,” said Maureen Malloy. “But BP programs his own. I think it would be silly to have me programming for a jazz historian.”

The music that appeals to BP’s old noggin is what he calls “the melodic stuff with no expiration date,” most of it recorded decades ago.

A survey of the playlist from one of his last shows before his stroke is a ramble through classic jazz interpretations of American Songbook standards. Like the theme song from the 1944 film “Laura,” played by saxophone legend Coleman Hawkins. Or Tony Bennett singing “My Foolish Heart” accompanied by pianist Bill Evans. A few Philadelphia artists were sprinkled into the evening, including Perkins’ longtime friend, saxophonist Bootsie Barnes, and vocalist Phyllis Chapell, who dedicated her latest album to BP. The mix of music was an image of the man who chose it: smart and warm and nostalgic, displaying impeccable taste and a steady, low-key, and almost offhand hipness.

In mid-December, as he planned his return to the airwaves, Perkins was worried that some physical effects of his stroke — a few fingers that weren’t obliging — might compromise his technical performance in the control booth. But his well-honed approach to the music would remain unaffected.

“I look to my dad and my older brother,” Perkins said, “and I guess I was just programmed to do what I do. People say, ‘You ought to give it up, man, go retire somewhere.’ Why? I’m the only one that’s doing this thing on regular radio and I enjoy very much what I’m doing, and the feedback that I get from people who enjoy it. Maybe it’s one of the high points in their life. This music conjures up some beautiful memories. You can find some solace in what you like.

“Music,” said BP about the GM. “That’s our savior, man.”