A print of the Emancipation Proclamation signed by Lincoln with deep Philly ties will be auctioned by Christie’s

The authorized edition of the historical text is part of Christie's upcoming "We the People: America at 250" auction, which also includes an early draft of the U.S. Constitution.

Less than a year after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, while our nascent nation was still in the throes of the Civil War, two industrious Philadelphians devised a plan to help raise money for injured Union soldiers, war widows, and children left orphaned by the war.

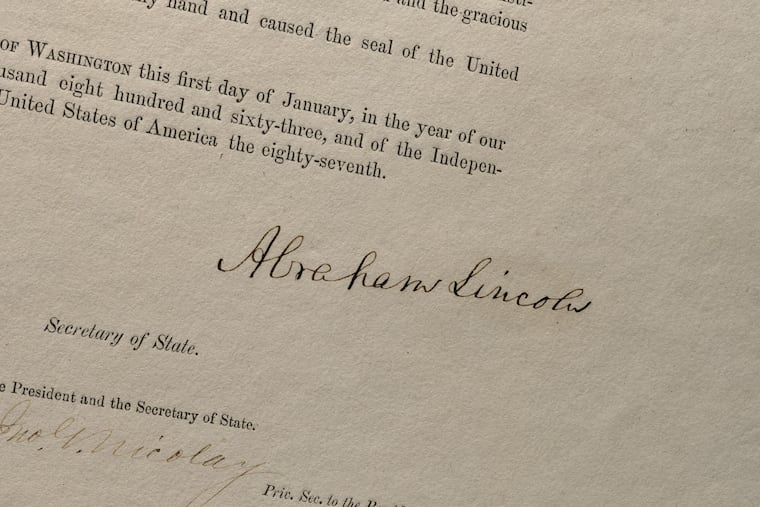

Charles Godfrey Leland, a Union Army veteran of the Battle of Gettysburg, and George Henry Boker, a founder of the Union League of Philadelphia, had the text of the Emancipation Proclamation printed in Philadelphia in 1864. They got Lincoln to sign 48 copies and then sold them for $10 each, which was about a week’s worth of wages for a day laborer at the time.

Just 27 copies are still known to exist of what is referred to as the Leland-Boker broadside — the only authorized, printed edition of the full text of the proclamation to be signed by Lincoln — and one of them will be sold by Christie’s next month as part of its "We the People: America at 250" auction.

Yes, even a British auction house is getting in on our Semiquincentennial celebrations (though, to be fair, the sale is taking place at Christie’s New York offices).

The broadside, which was also signed by Lincoln’s secretary of state, William Seward, and his private secretary, John Nicolay, is expected to fetch somewhere between $3 million to $5 million when it’s auctioned on Jan. 23.

Peter Klarnet, senior specialist for Americana books and manuscripts at Christie’s, said that while the Emancipation Proclamation did not end slavery, it was the document that paved the way for the 13th Amendment.

“It’s part of our historical evolution. As our society changes and society’s mores change, we adjust our founding documents accordingly,” he said. “The Emancipation Proclamation is really a reaffirmation of American freedom in so many ways. It’s now extending that freedom to people who didn’t have it before and extending the promise of what was in the Constitution.”

Both Leland and Boker were born into well-to-do families in Philadelphia, attended Princeton University, and became writers. Leland was a journalist and author with an interest in folklore and the occult, and who traveled extensively through Europe. Boker was a poet, playwright, and diplomat who served as an ambassador to Turkey and Russia. Both men are buried at Laurel Hill Cemetery.

It’s unclear how the two met, but Klarnet said they most likely traveled in similar social circles in Philadelphia and were organizers of the Great Central or Sanitary Fair held at Logan Square in 1864, which raised funds for supplies and necessities for the Union Army. The fair — which Lincoln attended with his wife, Mary — brought in more than $1 million.

At these fairs, which happened in numerous Union cities, autographs of famous Americans were sold to raise funds, according to Klarnet. The year prior, Lincoln’s signed original manuscript of the Gettysburg Address sold at a similar fair in New York City for $1,000. At a fair in Chicago, Lincoln’s handwritten original draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was auctioned off for $3,000, only to later be destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. The official proclamation is housed at the National Archives in Washington.

Leland and Boker commissioned their copies to be printed in Philadelphia by Frederick Leypoldt as broadsides on very fine paper with wide, dramatic borders.

“Surprisingly, not all sold,” Klarnet said. “A few were sold at other fairs and others were donated to institutions.”

Of the 27 left known in existence, only a half-dozen or so are in private hands, Klarnet said. Most are in institutional collections, including here in Philadelphia where we have three — one at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania, one at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries (which also has two marked-up proofs of the broadside), and one at the Union League. The National Constitution Center previously had one on loan from a private collector, but it was sold for $4.4 million at a Sotheby’s auction in June to a hedge fund billionaire.

The first known owner of the authorized edition being sold by Christie’s was Philip D. Sang, a corporate executive from Chicago whose collection was sold around the late 1970s. The current owner is the Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History in New York City, which is selling the piece to benefit its acquisitions and direct care fund, according to Klarnet.

Other works with notable Philadelphia ties in Christie’s upcoming “We the People: America at 250″ auction include an edited Committee of Style draft of the U.S. Constitution, which was written in Philadelphia five days before the final draft was printed; a U.S. Centennial flag; and a 1779 letter written by Benjamin Franklin to his friend David Hartley.