Young Afghan women in a N.J. English class share dreams in their writings: ‘I request you not to leave us’

Through lectures and writing assignments, the girls are encouraged to express themselves to cope with depression. “It’s more than a class,” said their teacher. “It’s like a therapy session."

Before the Taliban took over their country, these Afghan girls were like most teenagers. They attended school, went to the gym, and hung out with their friends. Some had jobs and were pursuing their dreams.

And then life drastically changed when the last U.S. troops left their homeland in August 2021, ending the U.S. military presence there after nearly 20 years. The Taliban took control, and Afghanistan’s government became the “most repressive country in the world” for women’s rights, according to the United Nations.

Girls were barred from attending secondary school beyond sixth grade, or enrolling in universities, and were restricted from most public spaces, including parks, unless accompanied by a male relative. They were also prohibited from most forms of employment. A decree was passed by the Taliban requiring women to wear clothing that covered them from head to toe, including a face veil.

» READ MORE: This Princeton educator teaches virtual English classes to Afghan girls around the world

For hundreds of these young women, their education now comes in the form of a weekly online course with Seth Holm, a world languages teacher at the Hun School of Princeton, providing a tether to dreams that have been shattered.

Through class lectures and writing assignments, Holm encourages the girls to express themselves to cope with depression and isolation and seek hope for better days.

“It’s more than a class,” said Holm. “It’s like a therapy session.”

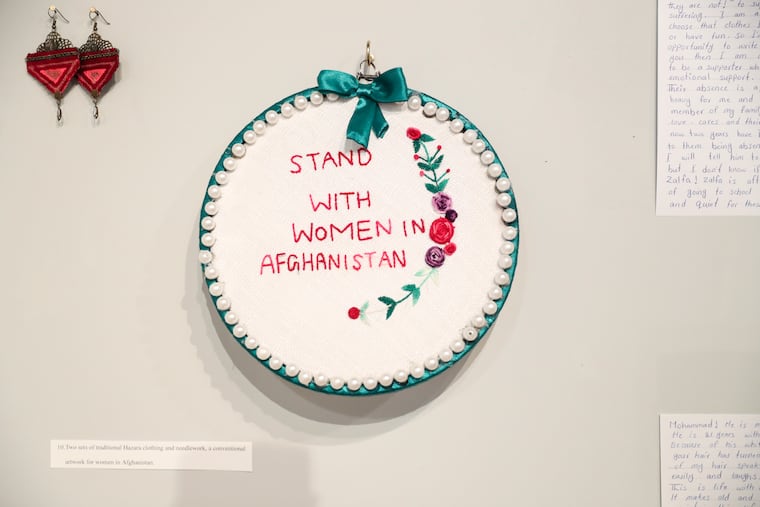

What began with a single class of about 20 students has evolved with some of the girls’ help to become the Afghan Education Student Outreach Project, now providing nearly 200 young Afghan women online classes with American mentors to prepare them for high school and college. Here are some of the stories of Holm’s students that were shared in classes and at a recent exhibit in Lawrence. Their last names have been withheld for their protection:

Mahdia, 16

Mahdia had just finished 11th grade at Azadagan High in Kabul, where there were very few subjects she didn’t enjoy. Among the list of subjects she loved: chemistry, algebra, history, art, geography, physics, English, languages.

Then the Taliban took control, and girls her age were banned from school.

“I had no choice but to sit at home,” she wrote in an essay for Holm’s class. Holm has encouraged the girls to use their writings to begin to heal from the trauma.

A few months later, after receiving threatening messages from the Taliban, her family fled to Pakistan in January 2022. Without a long-term visa, Mahdia was not allowed to attend public school there. So, the family began looking for ways for her to get an education in the United States or another country.

“I have not been able to do anything outside my house. The situation was worsening day by day,” she wrote.

She started taking part in Holm’s virtual English class, and this spring, she was selected to receive a full scholarship from the Hun School under the Afghan Education Student Outreach Project, one of two awards the school has pledged annually. The scholarship would allow her to enroll as a freshman in the fall and spend four years at the exclusive boarding school, where tuition is about $73,000 a year — but Mahdia was turned down three times for a student visa, and it appears likely that decision won’t change.

After Mahdia and her family left Pakistan in May, they went to live in Brazil at a refugee camp. She remains a student in Holm’s class virtually and teaches English to younger Afghan girls remotely.

Malika, 22

When her family was returning home from Uruzgan, Afghanistan, Malika was separated from both of her parents. She doesn’t share the circumstances in her essay, except to say she was left as caretaker for her four siblings.

She has no idea whether her parents are still alive. She has accepted the responsibility of taking care of her siblings, but she misses her parents and their support.

“I need the love of my parents every day. Their absence is a great sadness,” she wrote in a four-page letter as part of the Hun class. “So, I consider myself suffering.”

Like her peers, Malika misses her old life. She cannot work or study or wear clothing she likes.

“I cannot travel alone or have fun,” she said.

Some of her siblings, too, are struggling. The 8-year-old believes his father will return one day and buy him a guitar. A sister mumbles in her sleep about not being able to attend school; she has not been in two years. Her 13-year-old sister is completing her last year of school. The Taliban allows girls to study until sixth grade.

“This is life without parents, education, activity!” she wrote. “But I maintain this life and try to be strong and energy to my siblings that they can find their way.”

Malika said writing the heartfelt letter brought comfort and gives her hope for the future. She said Holm inspires the girls like a father, teacher, and brother.

“Every Afghan woman like me has their bitter stories! As a young Afghan woman and a Hazara girl who has always been subjected to violence and oppression because of my religion and being a woman, I request you not to leave us and to support us,” she wrote.

Sakina, 17

Sitting in class next to her best friend on a Saturday afternoon, Sakina was startled by a loud noise, not sure at first what it was.

Then, the room filled with smoke. She heard whistling in her ears. Her classmates were screaming.

“Escape everyone! Go to your homes!” the teachers yelled.

The powerful explosion in May 2021 had ripped through the Sayed Ul-Shuhada High School in Kabul, killing at least 90 people and injuring many more.

It occurred as residents, many of them of the Hazara ethnic minority, were preparing for the end of the holy month of Ramadan, the streets packed on that Saturday afternoon. The school was filled with girls; boys attended in the morning.

“I could not move, my feet were numb, but I tried hard to move,” Sakina recalled in a class essay assignment.

Then a second explosion hit, followed by a third. She ran through the streets, frantically trying to reach her parents. At the same time, her oldest brother, Akbar, went to the school searching for Sakina.

Finally, Sakina arrived safely at her home. She saw her father, relieved at the sight of her, cry for the first time in her life.

“I hugged my mom; I cried more and more. I was in shock because I did not know what happened to my classmates, friends and other students,” she wrote.

The next day, she returned to the school where she found blood-covered books and backpacks. She learned that her best friend, Malika, had died in the massacre.

“I make myself strong and brave to continue my life. Just for my dreams, for Malika, for her empty place in my life,” she wrote.

Samira, 19

Samira recorded Aug. 15, 2021, in her diary as “the saddest day of my life and maybe not only for me, but this day will be recorded as the saddest day in the history of Afghanistan.”

After morning prayer, she began checking her social media accounts for news about the war and the Taliban. First, she learned about the fall of Balkh, a province in northern Afghanistan. It would only get worse.

“The bad news and heartbreaking, sad photos continued until I don’t remember exactly, but I think there was a story on Instagram that shook my soul when I read it,” she wrote. “Of course, even though I was very scared, I couldn’t accept that news in my heart. It said, ‘There is a possibility that Kabul will fall to the hands of Taliban in the next 72 hours.’”

Later that day, Samira and her mother, on their way to the bank, turned back amid news that the Taliban had reached the gates of Kabul. People were frantic, scurrying to get home.

“When I got home, I was crying like an idiot! The reason behind my tears was that I was thinking, what would happen to our Afghanistan afterward, what would happen to our beautiful Kabul and our poor people?” she wrote.

President Ashraf Ghani fled the country, saying the Taliban had won. Samira eventually fled to Islamabad in Pakistan.

Zahra, 21

Left with little chance to get an education she desperately wanted, Zahra fled in 2021 from Afghanistan to the United States to enroll at the Hun School.

The youngest of eight siblings, she was the last to leave Kabul, at age 19. While her mother remains in Afghanistan, and a few siblings came to the United States, her father escaped to Iran.

“It was the hardest decision of my life,” she recalled in an essay and an interview. She also never forgot about the girls she left behind unable to go to school.

She settled into the boarding school in Princeton and worked to perfect her English. With two friends, she created an online English class for Afghan girls and recruited Holm to help with the four-week course.

The biggest changes were the cultural differences, Zahra said. She was surprised by how friendly her teachers and peers were, and how they would urge her to “go for it.”

“Back home, this is not possible, especially if you are a girl,” she said.

While completing her studies, Zahra and a fellow boarding student tutored Afghan girls virtually in the middle of the night (because of the time difference). She graduated from Hun and enrolled in a university in Ohio, where she is a sophomore science major.

The program she started has grown to five classes. There is also a study-buddy program that assigns Hun students to mentor and tutor Afghan girls, with scholarships to pay for internet access and other educational opportunities.

After college, Zahra, now 21, wants to return to her homeland to set up a business to help educate girls.

“I try so hard to just forget about Afghanistan. But I can’t,” she said.