With a college mindset and character education, these scholars attend one of the few suburban N.J. charters

Every classroom is named for a college or university — meant to place the students in the mind-set to pursue a higher education, Wilson said. School officials refer to them as “scholars.”

When Richard Wilson Jr. told his wife in 2007 he wanted to start a charter school in South Jersey, she laughed — and then helped him launch the Benjamin Banneker Preparatory Charter School.

It took the couple years to complete the application and open the school with 120 sixth and seventh graders in a Willingboro church basement in 2012. Today, the school enrolls about 360 students in kindergarten through eighth grade at two locations.

Headquartered on a sprawling campus in Westampton, the school is among only a handful of 87 charters in New Jersey located outside troubled urban districts like Camden, Newark, and Jersey City, where many parents seeking other options for their children have fled traditional public schools.

“It’s about the children we serve,” said Wilson. “We want to give them the best education possible.”

A former youth counselor, Wilson, 51, of Westampton, said he decided to start the school after reading a Forbes article about a teacher who founded a private school in Harlem. A visit to that school confirmed the decision for Wilson and his wife of 23 years.

» READ MORE: Camden's first charter school, LEAP Academy, marks 20th year

The school is named for Benjamin Banneker, son of a once-enslaved man, who was a self-educated astronomer and mathematician and a civil rights activist. He produced one of the country’s first almanacs. The school focuses on math and science.

The walls in the buildings at the 11-acre campus are stenciled with inspiring messages, including Gandhi’s “You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” The Westampton campus has about 160 students in kindergarten and sixth through eighth grades; the remaining 200 students in first through fifth grades are housed in a Willingboro campus.

Every classroom is named for a college or university — meant to place the students in the mindset to pursue higher education, Wilson said. School officials refer to them as “scholars.”

The charter school attracts mostly children from Willingboro schools, where students have struggled recently on state standardized tests. Other students come from nearby districts, including Burlington City, Burlington Township, Delran, and Delanco, Wilson said. There is a waiting list of about 800 students.

Banneker students have performed slightly better than their counterparts in Willingboro public schools on state tests in math and language arts. But their scores have lagged state averages, a frequent criticism about charters.

Wilson said the school has added programs, including tutoring before and after school, beefed up the curriculum, and hired a reading specialist to better prepare students when the tests, suspended for two years because of the pandemic, resume. He takes pride in other milestones, though, like the fact that one of his first students recently graduated from college with an education degree.

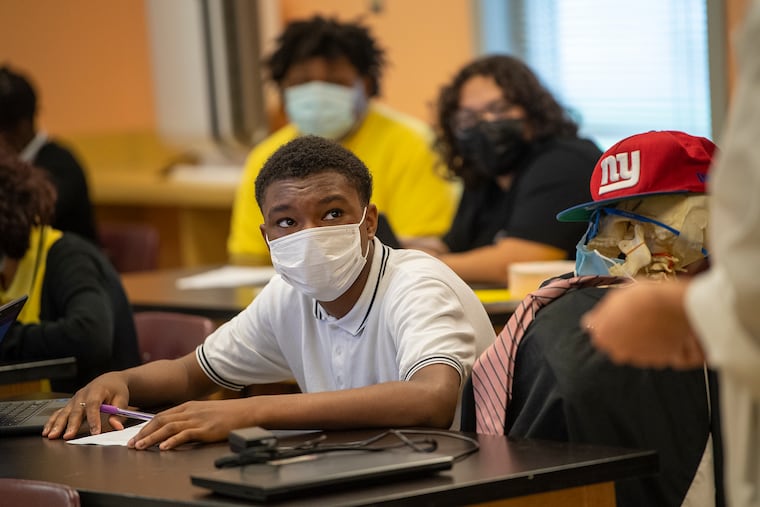

On a recent morning, eighth graders in Adam Brickey’s science class were working on a 3D STEM project, where a lesson about the spotted lanternfly was a big hit. Students love their “classmate” Dexter, a skeleton Brickey brought in last year as a morale booster. Across the hall, a civics class was studying the Louisiana Purchase. In another building, kindergartners — all with their own Chromebooks — completed assessments.

“This is the best place I’ve worked, hands down. It’s awesome,” said Brickey, 36.

There are only 10 students in the eighth-grade classes and 20 in the lower grades. Yellow-and-black uniforms are mandatory, as well as character education, which gives every student lessons about patience, honesty, and kindness.

Wilson has a strict discipline approach, but stops short of kicking out students, if possible. Instead, students who break rules are given extra assignments through an in-school suspension known as “a behavioral reflection program,” a quiet time to consider their actions.

Eighth grader Raymond Hall, 13, of Willingboro, said his parents thought he would benefit from the tough discipline when he enrolled three years ago. The honors student said the culture “kind of grew on me.”

”It’s strict but not too strict,” said Hall. “You get rewarded when you do what’s right. It’s good here.”

Dion Barber, a mother of three, enrolled her oldest daughter, Avana, in Banneker’s inaugural class in 2012; a second daughter, Parker, in 2017; and the third, Cameron, 12, currently a sixth grader, in 2019. Barber joined the school’s board and has been president for two years.

“I absolutely believe in this school,” she said.

There is a growing need for charter schools as an alternative, especially for students interested in specialty subjects, said Harry Lee, executive director of the New Jersey Charter Schools Association.

New Jersey’s charter schools, which are publicly funded and privately operated, are located in about 40 districts statewide, he said. If there are more students than spots at a school, schools are required to create a lottery and a waiting list. Riverbank Charter School is the only other charter school in Burlington County.

“It’s really important that we have a diverse school system that can meet families where they are,” Lee said. “They’re doing a great job serving kids.”

Wilson, who grew up in Ewing, said he models his approach for leading the school after his father, who was a Pentecostal preacher for 38 years.

“He instilled a lot of morals and values that I try to govern the school by,” said Wilson, who plays the keyboard for local churches.

Wilson says he knows every student’s name and background, which doesn’t surprise his longtime friend Rita Roberts, who serves on the school’s foundation board. “When he goes all in, he goes all in,” she said.

He admittedly gets attached to his students but says he tries not to let any problems overwhelm him.

“I always tell them, ‘Mr. Wilson loves you.’ They know that I will give them the shirt off my back. I do what I can.”