Police in Chester Township wielded a loitering law to harass and illegally detain residents, lawsuit says

The plaintiffs say they were doing nothing more than standing in front of their homes when they were arrested. All charges against them were later dismissed.

Seven Black Chester Township residents have filed a federal civil rights lawsuit against the tiny municipality’s police department after they were arrested in the span of 10 days by the same officer for what they say was nothing more than standing in front of their homes.

One of the plaintiffs, Keith Briggs, was arrested twice in two days under the same loitering statute, which his attorney, Kevin Mincey, says is overbroad, prejudicial, and unconstitutional. Another, Ed Baldwin, said he was tackled to the ground by officers who had minutes earlier detained his cousin for allegedly loitering.

All of the charges filed against Briggs, Baldwin, and the others — ranging from summary offenses to resisting arrest — were later dismissed by the Delaware County District Attorney’s Office for lack of evidence.

But the residents aren’t satisfied with that outcome. They say the police conduct in their cases demonstrates a clear, deliberate pattern of harassment, and shows that their township’s 16-member police department is in need of reform.

“Knowing that it’s the same officer who’s involved in these four separate arrests, that’s not a person that needs to be a police officer anymore,” said Mincey, of the Center City firm Mincey Fitzpatrick Ross. “We trust [police] with the power and the authority to enforce laws and protect and serve people, and when they act the way they did in these separate incidents, that proves they don’t have what it takes to be a police officer we can count on.”

Chester Township’s solicitor, Kenneth Schuster, did not respond to numerous requests for comment. Nor did Calvin Bernard, the chairman of the township’s supervisors and its police commissioner.

The complaint names Officer Pasquale Storace as the officer who made all of the arrests but says colleagues assisted him. Storace also did not respond to a request for comment.

An attorney for the township, Suzanne McDonough, filed a motion to dismiss the lawsuit this week, saying the residents had failed to prove a pattern of harassment.

“There are no facts that these particular plaintiffs were treated the way that they allege based on race, and no facts that they were treated differently from other similarly situated individuals who were not in a protected class,” McDonough said.

Baldwin says what he wants, above all else, is for his neighbors in Chester Township, a Delaware County community of about 4,000, to feel safe.

“What really upset me is that they never gave me a chance to explain myself,” Baldwin, 50, said in an interview last month. “You shouldn’t just jump the gun and detain someone, whether white or Black. ... I wasn’t doing anything illegal. I’m just going in my house.”

Baldwin said he was coming home from a restaurant with his wife in September 2019 when he saw his cousin, Brandon Alvin, being detained by officers on their block in Chester Township. His crime? Loitering in front of the house he lived in, Mincey said.

The officers had Alvin — who is also a plaintiff in the lawsuit — pinned to the ground, and had just blasted him twice with pepper spray, Baldwin said. He said he stood on the sidewalk and watched the incident unfold mere feet from his front door.

Then, he said, one of the officers accused him of loitering and ordered him to go inside. At the time, Baldwin said, he had a fractured knee from a car accident, and told the officers he needed to wait for his wife to hand him his walker before he could move.

Rather than allow him to wait, Baldwin said, the officers pushed him to the ground and placed him under arrest for loitering.

Chester Township’s loitering statute was adopted in 1990, four months after a nearly identical measure was added to the books in the city of Chester that made it illegal for anyone to loiter in a “high drug activity area” without “lawful and reasonable explanation for his presence there.”

Chester City’s statute faced multiple legal challenges, including a 10-year battle in Superior Court, which ruled in 2012 that the measure “affords too much discretion to the police and too little notice to citizens who wish to use the public streets.” The judges deemed the statute overly vague and unconstitutional, and it was removed from the city’s municipal code.

But in neighboring Chester Township, a similar prohibition against loitering has remained — complete, Mincey said, with a requirement that anyone who lingers in an area governed by the statute must have a “lawful purpose” to do so. That is the very language the court found objectionable when it struck down the law in Chester City.

“Taken as individual cases, they may seem as small injustices,” Mincey said. “But on a large scale, if this happened in Philadelphia or Harrisburg, it’s a bigger story.”

Days after Baldwin’s arrest, the Briggs family encountered township police officers at their home, a few blocks away. Keith Briggs and his cousin Rahmir Briggs were standing outside the latter’s home, watching as police officers chased, tackled, and arrested a group of Black men on Briggs’ front lawn.

As the cousins watched the arrests, officers ordered them — unlawfully, according to Mincey — to go inside. When they refused, both men were taken into custody, charged with violating the loitering statute and resisting arrest.

The next day, after Keith Briggs’ mother came to pick him up from jail, the officers returned to the family’s home. There, they arrested Briggs’ cousin Kimyuatta Lewis and his aunt Rachel Briggs for loitering. When Keith and Rahmir Briggs tried to speak with the officers, they, too, were taken into custody, charged again with resisting arrest and other offenses.

In cellphone footage recorded by Keith Briggs’ mother, and reviewed by The Inquirer, during the incident, none of the officers explains why they’re arresting the group, despite pleas from other family members.

All of the charges from that arrest were later dropped by county prosecutors.

The Briggs and Baldwin families — who live a few blocks from each other — say the ordeal was deeply unsettling.

Rachel Briggs said she lives in fear, paranoid that the officers who arrested her relatives in front of her will “come back to finish what they started.”

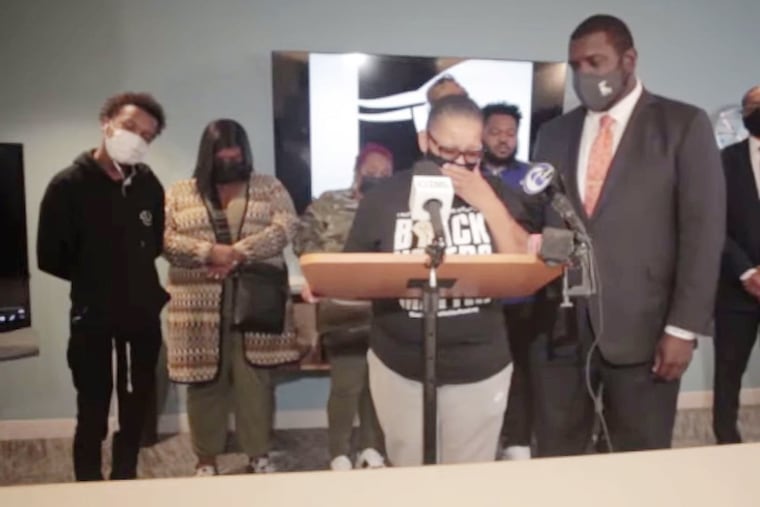

“We cannot allow our police to terrorize us in the name of law enforcement,” she said last month at a news conference to announce the lawsuit. “The police are supposed to protect and serve our family and others in Chester Township, but for far too long, the police have been responsible for terrorizing our neighbors and family.

“And we are being held accountable for their obvious wrongdoing.”