His shooters may never get his letter of forgiveness, but maybe it will help others drop their guns | Helen Ubiñas

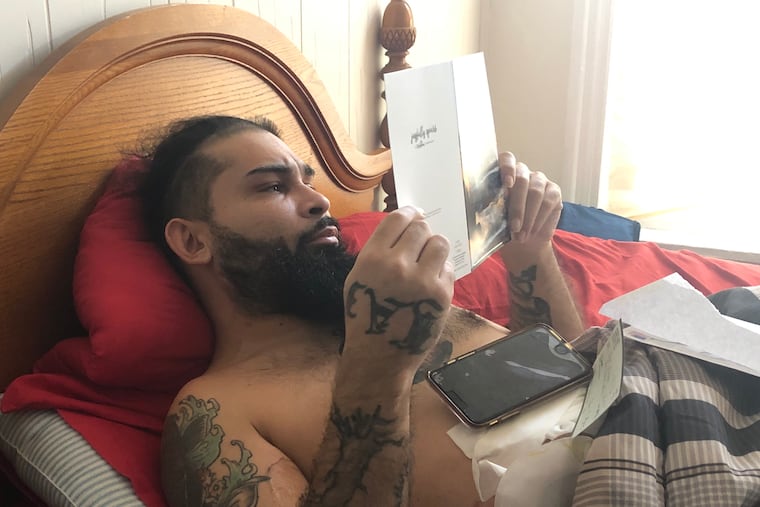

I brought Luis Berrios some red seedless grapes, and a card from one of the many readers moved by his stunning response of forgiveness to the people who shot him.

I’d first met him in November at Temple University Hospital after a bullet had pierced his back during an attempted robbery outside his Philadelphia home. The 35-year-old lay in his hospital bed, attached to multiple machines and craving food — grapes especially, he told me while being fed through a tube.

It was during those long weeks in the hospital that, first in his head and then on paper, he drafted and redrafted a letter to the men, who have yet to be apprehended, who shot him and ran off with nothing.

“I’m not mad, I’m not angry,” he wrote. ”I’m not looking for vengeance. I’m not looking for you at all. I’m sad, I’m sad that you shot me and that you hurt me.”

The grace in those words, which I wrote about, touched many people. His aunt Wilma Berrios, who stopped by while I was visiting on Monday, was proud of her nephew, even if she wasn’t sure she could do what he did.

Luis Berrios is now back home, but the men are never far from his thoughts. Partly, he admits, because he’s afraid. Of being just steps from where he was shot, of being dependent on the many security cameras affixed to his house that offer only a fleeting sense of safety.

But also because he’s decided that even if the men who shot him never see the letter, he’d like to get it into the hands of other young men who might be headed down the same path.

“My hope is that my shooters see it," he said. "Will they confess? Probably not. But this is just not for my shooter, it’s for that young bull who has a gun, it’s for that guy who just spent $250, his last $250, on a gun, and he just thinks he’s, like, the man. For that person who thinks, ‘I’m broke, let’s go rob somebody.’ I want them to understand that they’re changing lives out here, that they changed my life.”

For so many, the consequences of gun violence are either life or death. Not Berrios, who spends his recovery peering through cameras and his bedroom window. He is a reminder of what happens to many more whose lives are forever changed by wounds less obvious.

The bullet that scrambled Berrios’ insides didn’t affect his ability to walk or talk, even if the breathing tube turned his voice into a gravelly whisper. Doctors say another six months and he can hopefully reclaim his life and job at Philadelphia Technician Training Institute, where he first learned welding and then got a job to place others in the trade.

But how long before the nightmares stop? Before he can overcome the fear that rushes in when his mind goes back to the cold night of Nov. 12, when he fell to his knees and begged the 911 operator not to let him die? The officers who responded scooped him into their car and took him to the hospital. Berrios doesn’t know their names, but he’d like to thank them someday for saving his life.

He’d like to move, maybe to another neighborhood. His family thinks he should go live with his mom in Florida. But trauma travels.

On the rare occasions that he does leave his house, mostly for doctor’s appointments, he can’t help but search people’s faces on the street and wonder if they know something. When he sees someone who he is almost sure is one of his assailants, he doesn’t call police, because he knows how many black and brown men’s fates have been sealed by little more than an “almost sure.”

He’s never sought mental health services, he concedes. But now he wishes he had someone to talk to, a professional.

In the meantime, he wants to make copies of his letter, and have friends help him hand them out and post them around the neighborhood.

Even if it never gets to the guys who tried to rob him, maybe someone might read it and put down their gun.