Philly domestic violence victims can now get free Amazon Ring doorbells — despite lingering privacy concerns

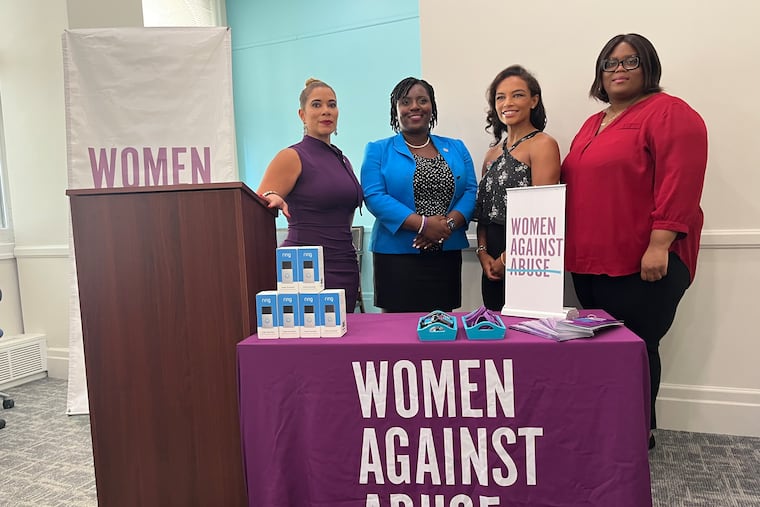

Ring pledged on Thursday to donate up to 1,000 camera-equipped smart doorbells and subscription plans to Women Against Abuse

Domestic violence victims in Philadelphia will now have access to free Ring doorbells through the city’s leading domestic violence service provider.

Ring pledged on Thursday to donate up to 1,000 of the camera-equipped smart doorbells and subscription plans to Women Against Abuse, a nonprofit advocacy group founded in 1976 that provides domestic violence services to over 10,000 people each year. The donation comes amid an alarming surge in violence against women since the pandemic began — and also at a time of heightened scrutiny over the Amazon-owned surveillance giant, which recently came under fire again for its data-sharing practices with police departments nationwide.

Joanna Otero-Cruz, executive director of Women Against Abuse, said the home security systems are in high demand among people fleeing violence and starting new lives.

“It’s one of the biggest requests from our legal center clients, besides going to court,” she said.

Cameras can also help domestic abuse victims gather evidence in order to file a protection-from-abuse order — or prove that an abuser has violated an existing order, said Jamie Colleen Miller, a board member at the nonprofit who is a domestic abuse survivor.

Cameras also provide a sense of personal security for people coping with years of trauma that can follow an abusive relationship.

For many, the fear is forever — even when no one is at the door.

“People really have no opportunity to escape this trauma and pain,” said State Rep. Joanna McClinton, who facilitated talks between Ring and the nonprofit. “For women that are able to get free from domestic violence, they’re still scared, and they still don’t have the means or the mechanisms to prove if they’re in perpetual danger.”

Reports of fatal domestic violence incidents have soared over the last year in Philadelphia. The Police Department attributed 43 murders in 2021 to domestic violence, compared to 18 in 2020 or 28 in 2019. During the pandemic, requests for protection-from-abuse orders, or PFAs, dropped precipitously, and the city’s two safe havens sat at low occupancy, a decline that advocates attributed to fear of congregate settings and an inability for many victims to flee their abusers during lockdowns at home.

Ring spokesperson Melissa Gansler said it has no role in distributing the devices and that Women Against Abuse would determine the needs among violence survivors.

But Ring’s ever-expanding network of police partners has raised concerns over domestic violence that occurs within law enforcement. In Philadelphia, at least six officers were charged in abuse cases in recent years, and the Police Department has tracked hundreds of domestic disputes reported by wives and girlfriends of Philly cops over the years.

Launched nearly a decade ago at a time home surveillance was less ubiquitous, Ring has grown to become the leading distributor of video doorbells, selling more than 1.7 million units in 2021. The company was acquired by Amazon in 2018, and has since expanded its reach by partnering with more than 2,100 police departments nationwide who use an app called Neighbors to solicit surveillance footage from Ring users.

Ring has maintained that it does not provide footage without the owner’s permission — or a court order — except in emergency situations. Last month, the tech giant admitted for the first time that it had in fact provided footage to law enforcement agencies on at least 11 “emergency” occasions this year alone, a revelation that ignited fresh scrutiny over the tech company’s data-sharing policies.

While some police forces in the Philly region are part of the Ring network, PPD spokesperson Sgt. Eric Gripp said the city’s department is not among them, and added that even obtaining a warrant for Ring footage can be difficult at times.

“It’s not that easy — and it shouldn’t be,” Gripp said.

Gansler could not confirm whether any footage had been released on an emergency basis in Philadelphia.

“Ring holds a high bar for the disclosure of customer information and deeply scrutinizes each emergency request,” Gansler said, in a statement. “Our policy, like many other companies, is to only fulfill these emergency requests when there is imminent danger of death or serious injury, which has included kidnappings, cases of attempted murder, and incidents involving the risk of self-harm.”

Gripp also could not confirm whether the department had obtained footage without a court order, though said it was possible in a time-sensitive emergency like an abduction.

In many cases, Gripp said Ring users willingly provide footage to the Police Department or post it publicly on social media. He said the department does not have remote access to livestream video.

Even within the department’s SafeCam program, a decade-old initiative that allows residents to register their private surveillance devices in a city crime watch database, Gripp said police do not have unfettered access to footage. The database tells police only where cameras are located, alongside the owner’s contact information.