53 years after Vietnam, he’s still searching for the Marine who saved his life. Can you help?

His name was Henry. He may have been from Philly. And when it mattered most, he stepped up.

Sometimes John Suzadail daydreams that he has already found Henry. Henry’s wife opens the door and directs him to a bar down the street. There he is — bartending, or sitting with a drink. It’s been 53 years; both men are in their 70s now, creaky with pain from the war and old age.

“You remember me?” Suzadail asks. In the apparition, he hugs Henry, tears running down his cheeks.

Then the daydream dissolves, and Suzadail, 73, is still searching for the man who saved his life.

Henry was the only Black Marine in an otherwise mostly white unit, Suzadail said, and the first Black person with whom he ever interacted. (Suzadail grew up in a small, mostly white town in Tamaqua, 90 miles north of Philly, where he still lives today.)

The two served together in Vietnam, in Combined Action Program CAP 3-3-6, stationed with about seven other Marines in the bush near the village of Tam Bảo. They spent “much of their time crawling through underbrush,” on land “honeycombed with enemy bunkers,” according to an on-the-ground report that Suzadail’s mother clipped from the local paper. The unit bathed only when the men found a stream they could dip their helmets into, Suzadail said; if they immersed themselves fully in water, the leeches would swarm.

During the short three and a half months Suzadail was with the unit as a medic, he didn’t get to know Henry well — he doesn’t even know his last name. The only thing he thinks he remembers is that he was from the Philly area, and even that he can’t say for sure. He believes Henry was just about his age. Because of Suzadail’s post-traumatic stress disorder, much of the details of his time in Vietnam are lost to him, except for strikingly vivid memories of the day he was wounded.

That was May 15, 1970. Suzadail, Henry, and the others set out to uncover a Viet Cong bunker they had spotted several weeks earlier. It was a misty day, cooler than usual; Suzadail offered to walk point, leading the patrol, because he knew where the bunker was. He traded with a Marine already in the lead, Steven Merrell, and began to scan the woods for danger. Then he felt a tug at his leg. He had tripped a wire connected to a grenade.

“I went to scream and it went off,” Suzadail said. The blast lifted him toward the sky; his legs felt like balloons. He spotted two Viet Cong soldiers in the forest and thought he saw a bullet tear toward him.

Then Henry scrambled to his side.

Henry, along with a South Vietnamese soldier who had been working with the unit, knelt beside Suzadail and patched him as quickly as he could, Suzadail said. The two rushed him to a medical evacuation helicopter, screaming along the way that Merrell had fallen and couldn’t be revived. They lifted Suzadail into the helicopter, placing Merrell’s corpse beside him. Rapidly losing blood, Suzadail began to go into shock.

In his dreams he often finds himself back on that helicopter, checking in vain for Merrell’s pulse, the door open and the chopper tipping sideways.

“For years I blamed his death on me,” he said of Merrell. They had switched places just 5 minutes earlier.

The last time Suzadail saw Henry was when he lifted him into the helicopter.

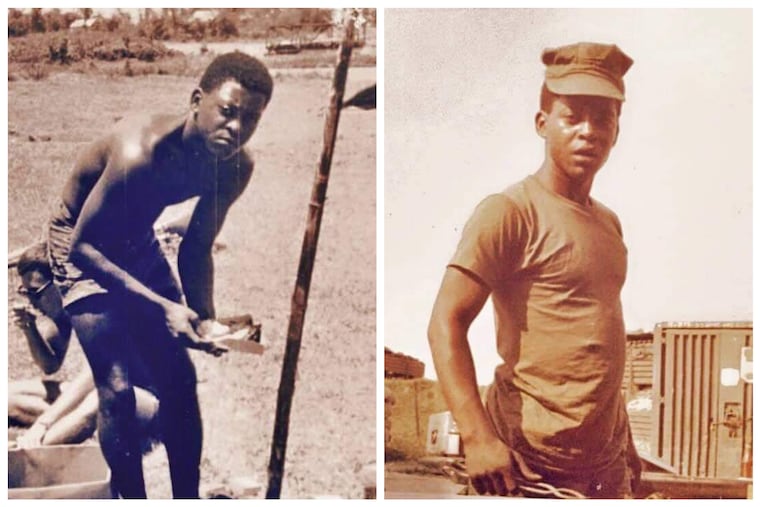

In the decades since returning home, Suzadail married and got a job at the post office, where he worked for 24 years. The VA diagnosed him with PTSD (“They gave me a psychiatric test and I flunked it royal,” he said) and he has gone to group therapy and reconnected with some of the other men he served with. Through them he tracked down two photos of Henry in Vietnam, one of him shirtless, bent over a tin can for cooking; the other of him in T-shirt and cap, mouth slightly open in surprise.

Over the years Suzadail has scoured casualty lists and Vietnam buddy finder sites, and visited comrades’ graves in Idaho and Mississippi. Still, he hasn’t found Henry.

A spokeswoman for the Marine Corps told The Inquirer it would be extremely difficult to locate Henry without a last name, since the Marines archives are not organized by unit.

Unsure where else to turn, Suzadail posted two photos of Henry on Facebook eight years ago. Every May he reposts, hoping for new leads.

“Been trying to find this Marine for a long time,” he wrote. “If you know Henry please contact me.”

Finding Henry wouldn’t exactly bring closure, or even relief — as Suzadail has gotten older, the pain in his legs has intensified; it’s a rare day when he doesn’t think of Vietnam now. But he wants to submit Henry’s information for a combat award.

“I want to thank him,” Suzadail said. “I never got to thank him.”

If you know who Henry might be, please write to zgreenberg@inquirer.com.