Stigma failed Kurt Cobain nearly 30 years ago and continues to fail people in addiction now | Opinion

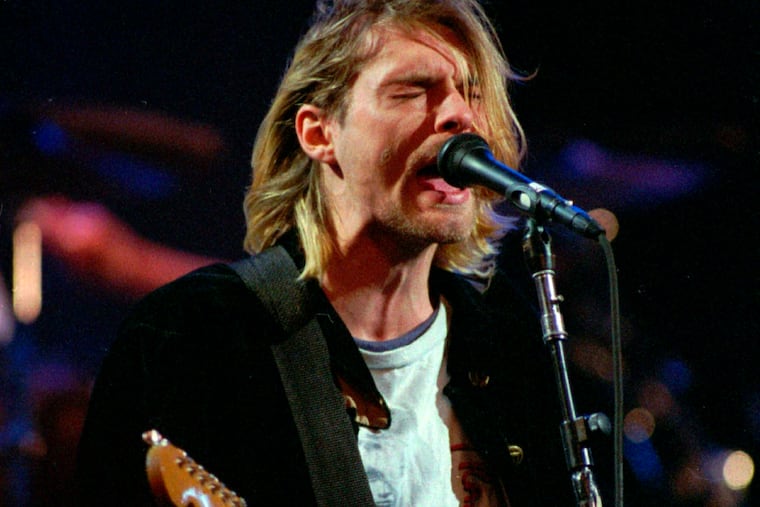

Kurt Cobain was the world’s biggest rock star. His path through addiction treatment was devastatingly common.

On or around April 5, 1994, Kurt Cobain died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the head, with a lethal dose of heroin in his blood.

The biggest rock star in the world was gone at the age of 27.

Few people had to deal with the sudden fame that the Nirvana frontman experienced — his album took the No. 1 spot on the charts from Michael Jackson before age 25. But there are parts of the rock legend’s story that are common among many people struggling with addiction: childhood trauma, housing instability, and chronic physical pain.

And, like so many others in addiction, Cobain lost many opportunities to feel better because of stigma and outmoded drug laws — both of which continue today.

» READ MORE: 100 years of dehumanizing opioid users must end | Opinion

Cobain used heroin for the first time in 1987 — recreationally, as he used many other drugs. That changed in the fall of 1991, when he was on the precipice of global fame. Cobain later wrote: “I decided to use heroine on a daily basis because of an ongoing stomach ailment that I had been suffering from for the past five years, [and that] had literally taken me to the point of wanting to kill myself. ... The only thing I found that worked were heavy opiates.”

During a 1992 tour, when Cobain couldn’t get heroin abroad, his stomach started bothering him again. He told the Los Angeles Times: “We went to this doctor who gave me these tablets that were methadone.” Methadone is a long-acting opioid that is used as a medication for opioid addiction. But Cobain stopped taking it in the U.S. and resumed using heroin.

Instead, at the end of the summer of 1992, Cobain entered a 60-day intensive detox program — at the Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles — where the goal is to support people while they go through withdrawal.

His daughter, Frances Bean, was born in August 1992 at the same hospital where her father was hospitalized for detox. His wife, Courtney Love, dragged him to her delivery room. Later she told Michael Azerrad for his book Come As You Are: The Story of Nirvana that Cobain was vomiting and fainting in the room as his daughter came into the world.

But inpatient rehab didn’t work for Cobain, and he started using heroin again. Like so many people with an opioid use disorder, detox and abstinence were just not the right path for him.

As a new dad, Cobain started a regime with a controversial addiction doctor who specialized in treating famous people, according to Charles Cross’ biography of Cobain, Heavier Than Heaven. He gave Cobain buprenorphine, a long-acting opioid that is considered even safer than methadone. Cobain wrote in his journal: “I was introduced to buprenorphine, which I found alleviates the [stomach] pain within minutes ... It acts as an opiate, but it doesn’t get you high.”

Buprenorphine is now considered the gold standard of treatment for opioid use disorder. But in 1992, the treatment was illegal.

It’s not clear from Cobain’s biographies exactly how consistent his buprenorphine treatment was. In the summer of 1993, the physician who prescribed him the medication died. So Cobain was on his own. And his addiction escalated.

Ten days before Cobain died, his wife and nine of his friends staged an intervention in his Seattle house. A few days later, Cobain entered abstinence-based treatment for the final time. He lasted two days.

What is so painful about Cobain’s journey is that it is so common. According to the American Psychological Association, upwards of 90% of people relapse following abstinence-based detoxification. A study comparing treatment options for opioid use disorder found that those who entered rehab or detox services were more likely to return within three months than those who received a medication like buprenorphine.

And yet, even as a person dies of an overdose every five minutes in the U.S., many people seeking treatment for opioid addiction do not receive medication.

» READ MORE: A safe drug treats opioid addiction. But most doctors can’t prescribe it. | Opinion

There is a false notion, rooted in stigma, that methadone and buprenorphine only “replace one addiction with another.” And it continues to drive policy. In truth, these medications remove cravings and the harms associated with addiction.

The goal of addiction treatment should be to ensure wellness and safety, not abstinence from any and all substances — Kurt Cobain tried that, multiple times, and it failed him. To address the overdose crisis, America must stick to evidence with empathy, not demands of sobriety. Because, as Love later said of the hardline approach to treating her husband: “It doesn’t work. It’s not real. It doesn’t work.”