Prosecutors hid evidence in 1988 murder case that sent Michael Gaynor to prison, lawyers say

Lawyers filed a petition seeking the release of Michael Gaynor, saying he was wrongfully convicted of killing a 5-year-old in 1988. The petition cited the work of a 2024 Inquirer investigation.

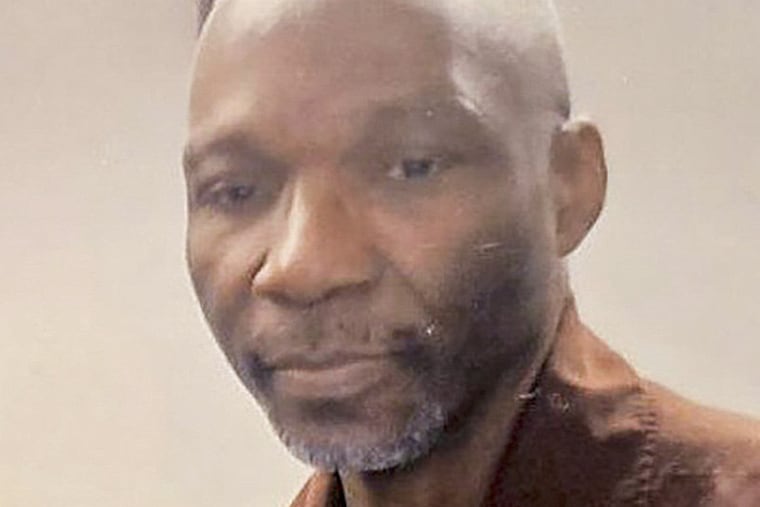

After 37 years in prison, Michael Gaynor — who was convicted of killing a 5-year-old boy in a Southwest Philadelphia candy store — could soon be released.

Lawyers from the McEldrew Purtell firm on Oct. 15 filed a petition under Pennsylvania’s Post-Conviction Relief Act (PCRA), saying that police and prosecutors suppressed crucial evidence pointing to another suspect, coerced witnesses, and relied on false testimony to convict Gaynor in 1988.

Gaynor is “wholly innocent,” lawyer Daniel Purtell told The Inquirer on Tuesday. “We request speed and transparency toward his exoneration.”

The District Attorney’s Office Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) has also been investigating the case since late last year. The office is expected to file a brief with the court in response to the petition.

The petition to free Gaynor relies on information detailed in The Inquirer’s six-part investigative series “The Wrong Man,” published late last year. The stories uncovered evidence that Gaynor was not the gunman or even in the store where a shootout between two men took the life of little Marcus Yates. The Inquirer’s investigation was based on thousands of pages of court transcripts and police paperwork, 21 witness statements, and interviews with more than four dozen people.

For more than a year, Gaynor, now 58, has had the most unlikely supporter: Marcus’ family.

Marcus’ mom, Rochelle Yates-Whittington, remained tormented by the tragedy decades later. She said she could find peace only by telling Gaynor and Ike Johnson, who was one of the convicted gunmen, that she forgave them.

But after speaking with each of them in prison video calls last year, she said, she no longer believed the police and prosecutors’ account of the crime and told her family Gaynor was not guilty.

“I am just so overwhelmed with happiness,” Yates-Whittington said this week after hearing about the court filing. “I just want to let Michael know I’ll be there for him once he’s released. I really hope this moves fast and his release is expedited.”

On the afternoon of July 18, 1988, Marcus, his two older brothers, and seven other children were crammed inside the tiny Duncan’s Variety & Grocery store, where they played three video games and eyed penny candy. Suddenly, two men blasted guns at each other, and the children were caught in the crossfire.

Marcus, who took a bullet to the head, died at the hospital later that day. His brother Malcolm survived being shot, as did another boy.

Gaynor lived around the corner from the store and was a low-level crack dealer. He was from Jamaica, and witnesses had told police that both shooters were Jamaican.

As part of the investigation, police seized a number of cars parked near the store, including Gaynor’s 1988 Nissan 300ZX. Four days after the shooting, he called the police to claim his car and spoke to Paul Worrell, lead investigator on the case. Worrell told Gaynor to come to Police Headquarters.

Gaynor said Worrell took him into an interrogation room, placed him in handcuffs, sat him in a chair bolted to the floor, and accused him of killing the 5-year-old boy. Worrell put a plastic bag over his head, Gaynor said, held it tight, and told him he had to admit to the killing. Gaynor said he told him he would talk but wouldn’t confess to a crime he didn’t commit.

Worrell has been linked to seven murder cases in the 1980s and 1990s in which defendants allege he and his partners coerced false confessions, falsified statements, slapped suspects while handcuffed to chairs, kicked their genitals, and threatened witnesses with criminal charges if they didn’t testify. Four men in those cases have since been exonerated, and another conviction was vacated.

Worrell, now retired, declined to comment.

In an interview last year,he told The Inquirer: “I hope Michael Gaynor rots in jail.”

Gaynor and Johnson, also known as Donovan “Baby Don” Grant, were convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life without parole. Johnson and other witnesses had always maintained Gaynor was not the other shooter.

In fact, witnesses had told police the other shooter was a man known on the street as “Harbor.” But detectives did not properly or substantively investigate Harbor.

When asked during the murder trial why police had not tried to find Harbor, Worrell replied: “I had investigated that name early on in the investigation, in the fall of 1988. …That name was a nickname. That name has never been attached to any human being that is in my capability to find nor within the New York Police Department’s capability to find. Our determination was that that person did not exist.”

The Inquirer determined that he was Paul Jacobs, also known as Peter J. Jacobs, a career criminal who was born in Jamaica and had lived in New York and Los Angeles.

Years after Gaynor and Johnson were locked up, Jacobs was shot dead on March 12, 1996, in a small ramshackle home in a South Los Angeles neighborhood wrought with street gangs and drug wars. He was 34.

Investigators knew Jacobs had faced criminal charges in New York and had an associated address that was part of the investigative records, according to the petition. Those details were concealed from the defense, the document says.

“The Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office has recently produced previously undisclosed documents confirming that Jacobs was identifiable through the New York prison system,” according to the petition.

Gaynor’s lawyers contend that suppressing that evidence amounted to misconduct that undermines the integrity of the conviction. Had it been disclosed, the petition said, “there is a reasonable probability the outcome of the trial would have been different.”

During the trial, the prosecution relied heavily on the testimony of traumatized children who identified Johnson and Gaynor in court. But three of the five children, now adults, said detectives and prosecutors had directed or coached them to do so, The Inquirer found. And police coerced Christopher Duncan, the son of the candy store owner, into recanting his original statement and adopting a false account implicating Gaynor, the petition said.

No forensic or physical evidence linked Gaynor to the murder.

“This was not a major lapse in judgment but a conscious decision to ignore leads that pointed away from Gaynor and toward the actual perpetrator,” his lawyers said in the court filing.

Since District Attorney Larry Krasner took office in January 2018, the convictions of 48 people have been overturned, according to data compiled by his office.

Many of the overturned cases date to the 1980s and 1990s, and police misconduct, fabricated statements, coerced confessions, and the withholding of exculpatory evidence were later cited as key factors in the wrongful convictions.