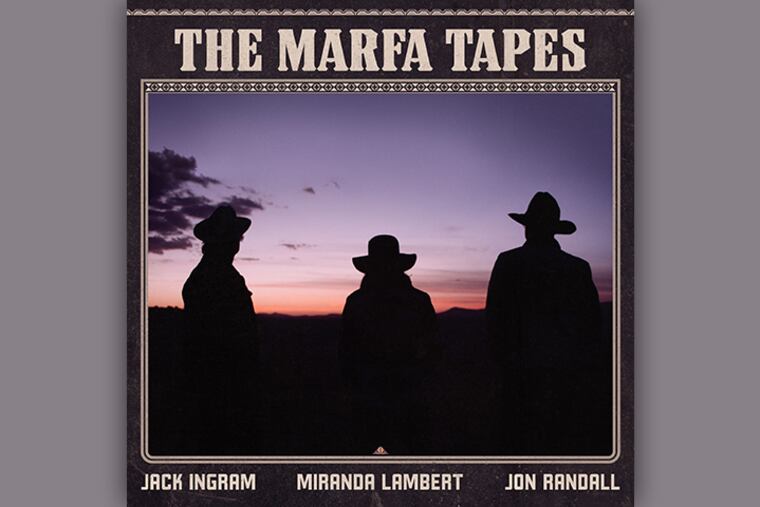

‘Marfa Tapes’ from Miranda Lambert and her Texas songwriting buddies is an unpolished marvel | Review

In other noteworthy new releases, Marianne Faithfull recites poetry and Topaz Jones makes "Don’t Go Tellin’ Your Momma" a captivating friends-and-family affair.

Jack Ingram, Miranda Lambert, and Jon Randall

The Marfa Tapes

(Vanner Records / RCA Nashville *** 1/2)

Miranda Lambert and her buddies Jack Ingram and Jon Randall first headed to remote Marfa, Texas, together in 2016. That initial retreat yielded a hit for Lambert in the devastating heartache song “Tin Man,” and the trio penned “Tequila Does,” a crowd-pleasing staple of Lambert’s arena-size country concerts on a return trip.

So with a pandemic putting a stop to the music business, what were the three Lone Star State friends to do but head back to the high-desert home of sculptor Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation and the atmospheric phenomenon of the Marfa Lights? Last September, Ingram, Lambert and Randall gathered around the campfire, seeking to recapture the in-person intimacy that COVID-19 has robbed so many musicians of.

Documenting their endeavors on an iPhone voice notes app, The Marfa Tapes is a marvelous off-the-cuff success. It’s intentionally unpolished: Logs crackle, the wind howls, border patrol helicopters fly overhead. Giggles and miscues are not edited out.

Of course, that lack of polish could come across as performative authenticity-flaunting. But The Marfa Tapes avoids such pitfalls, thanks to quality songwriting. “Tin Man” and “Tequila Does” are reprised, but the other 13 loosely performed songs are all new traditional country tunes of a high order.

Lambert is the focal point, and it’s a big deal for an artist of her magnitude to take a legitimate musical risk. But while she handles most lead vocals, Ingram and Randall are also showcased, and their musical camaraderie is unmistakable.

When Randall sings lead on “Homegrown Tomatoes” (not the Guy Clark song), Lambert’s concentration on her harmony vocal is evident. “Nailed it!,” she compliments herself, before the moment passes. Yep, you sure did.

— Dan DeLuca

Marianne Faithfull with Warren Ellis

She Walks in Beauty

(BMG ***)

“I have been half in love with easeful death,” Marianne Faithfull recites on She Walks in Beauty, her album of Romantic poems set to ambient soundscapes by Warren Ellis, of the Dirty Three and Nick Cave’s Bad Seeds.

She sounds earnest and committed to that line from John Keats’ “Ode to a Nightingale.” The 74-year-old Faithfull is a survivor: of Rolling Stones scandals and a suicide attempt, of heroin addiction and homelessness, of breast cancer and recently COVID-19.

Her long career has moved from conventional ‘60s Brit pop to punk fury (1979′s Broken English) to masterful interpretations (1987′s Strange Weather) to wise ruminations (2018′s Negative Capability, whose title also comes from Keats).

On She Walks in Beauty, Faithfull performs canonical poems from the early 1800s by Keats, Shelley, Wordsworth, Tennyson, and others. The gravitas of her posh, weathered voice suits familiar texts such as “Ozymandias,” “To Autumn,” and “The Lady of Shalott.”

Faithfull began She Walks in Beauty before the pandemic, and she and Ellis finished the project after her life-threatening bout with COVID-19. Ellis mostly stays out of the way of Faithfull’s engrossing vocals, content to create shimmering, undulating musical backdrops with the help of Brian Eno, Nick Cave, and cellist Vincent Ségal.

The readings are respectful, but not stodgy. They sound both traditional and contemporary.

— Steve Klinge

Topaz Jones

Don’t Go Tellin’ Your Momma

(New Funk Academy / Black Canopy **1/2)

Don’t Go Tellin’ Your Momma makes a lot of sense when you learn that rapper Topaz Jones, out of Montclair, N.J, is the son of a funk musician father and an activist-scholar mom. His music combines a funky, Sly and the Family Stone ethos of ensemble creation with a radical social consciousness, a potent mix that’s best taken down in one session.

Jones sings and raps alongside choirs, recordings of his friends and family, and his own layered voice. Crooning, exhorting or just letting bars fly, every voice on the album asks for the same recognition: for their Blackness and humanity to be treated as one and the same.

It’s a communal affair, from the image on the cover to an accompanying visual album that mines Jones’ hometown for material. The vibe is more hazy hangout than house party, but creating that group intimacy seems like what Jones was aiming for.

For all the sonic inspiration that the album takes from the past — velvety guitars, outer-spacey keyboards — Jones’ eyes are trained on the future. The things worth preserving will continue to be passed down, as he sings on the standout “Herringbone,” but what’s next? Could the generation of new forms, new ideas, and new expressions be the answer?

On “Baba 70S,” Jones remembers when it seemed like a pair of Nikes was all he needed. “But by the time I got ‘em they was out of style,” he raps. “God got a sense of humor, learn how to smile.”

— Jesse Bernstein