UpSide Classic: A Kensington-born musician taught hundreds of Mummers how to play their instruments

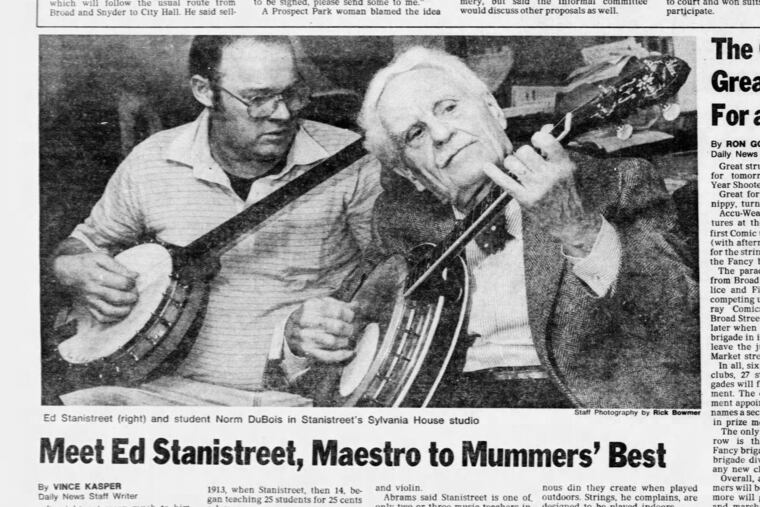

In his studio in the Sylvania House, a hotel-turned-apartment house on Locust Street near Broad, Stanistreet, taught Mummers and hundreds of other pupils the finer points of playing banjo, guitar, mandolin and violin.

This article originally appeared in the Philadelphia Daily News on Dec. 31, 1985.

It might not mean much to him, but when those showboatin’ string bands strut their stuff up Broad Street tomorrow, Ed Stanistreet will have a right to be proud.

Stanistreet, a Kensington-born musician, has taught hundreds of Mummers how to play their instruments.

They’re not all marching in this year’s parade — in fact, there will be only a handful of them in the competition. The others participated in years past, dating all the way back to 1913, when Stanistreet, then 14, began teaching 25 students for 25 cents a lesson.

“He certainly has added to the entire Mummers’ association,” Joseph Abrams, a banjo player for 32 years with Ferko, the winningest string band, said yesterday. "He has been an institution himself … "

In his studio in the Sylvania House, a hotel-turned-apartment house on Locust Street near Broad, Stanistreet, 86, has taught Mummers and hundreds of other pupils the finer points of playing banjo, guitar, mandolin, and violin.

Abrams said Stanistreet is one of only two or three music teachers in the region to take their students beyond the simple playing of chords. “He taught you the structure of why a chord is played and how it’s formed,” Abrams said.

Despite Abrams’ comments, Stanistreet, an amiable, soft-spoken man with silver hair, indefatigable energy, and perfect pitch, downplays his contribution to the Mummers.

He likes the sound stringed instruments make, but abhors the cacophonous din they create when played outdoors. Strings, he complains, are designed to be played indoors.

Stanistreet, a vegetarian who insists he’s never tasted alcohol, is a self-styled critic of the arts who volunteers his every Thursday as a traveling troubadour, strumming smiles out of patients at St. Christopher’s, Pennsylvania, and Thomas Jefferson hospitals.

In 1915 Stanistreet departed for Europe to study music. Hopping from Italy to France to Germany, he came in contact with some of the masters of the day, and they taught him enough to get him hired for a command performance in 1926 for England’s King George V.

“(The king) loved the sound of the mandolin,” Stanistreet said.

He returned home in 1935 with doctorates in music and physics and landed a job playing violin with Leopold Stokowski’s Philadelphia Orchestra. Later he performed on the mandolin under the batons of Arturo Toscanini and Eugene Ormandy.

About the same time, Stanistreet was developing a novel approach to music by creating on a mandolin the sound a painting makes. Like everything else, he said, colors emit vibrations, which the eye translates into certain hues.

What Stanistreet did was slow the vibrations of each color to correspond with a note on the musical scale. Red, for instance, translates to “A,” he said.

Sounds weird, but it apparently works well enough to have drawn the attention of Pablo Picasso during an art exhibition in France in the late ’40s. Stanistreet had been hired by a wealthy Frenchwoman to improvise his impressions of each painting when he encountered Picasso standing behind one of his pieces, "The Mandolin. "

Stanistreet said his musical interpretation of the painting so impressed Picasso that he asked Stanistreet to accompany him on a tour to promote his art. The musician declined, citing other commitments. The noted painter-sculptor made a note of Stanistreet’s unusual technique on the back of the piece, which now hangs in Philadelphia’s Museum of Art.

Stanistreet credits his vegetarianism for his ability to stay healthy, alert, and work long hours. Meat, he said, is “unnatural” and impedes the body’s energy flow.

He teaches 6 days a week, usually starting at 7 a.m. and often ending at 11 p.m. Despite his age and self-imposed heavy schedule, he sleeps just six hours a night.

“I never get tired …,” he said. “I don’t know what fatigue is.”