After staring death in the face, SW Philly men to hold peace rally at LOVE Park

“The biggest thing is we’re either going to stand together as one or we’re going to fall together.”

Cheick Diawara had to wait, with every excruciating swipe of his iPhone, to learn the fates of his relatives and friends.

It was Sunday, June 16, Father’s Day, a day meant to honor his dad, Mamadou, who had emigrated from Western Africa so his children, yet unborn, could have a better life.

It was also the day gunfire erupted at Finnegan Playground, halting a graduation celebration in the city’s West African community for several recent high school students, including Diawara’s younger brother, Mohamed.

That was the day Diawara, 21, thought up the Stand 4 Peace Rally, a brainchild born of fear and frustration, refusal and family.

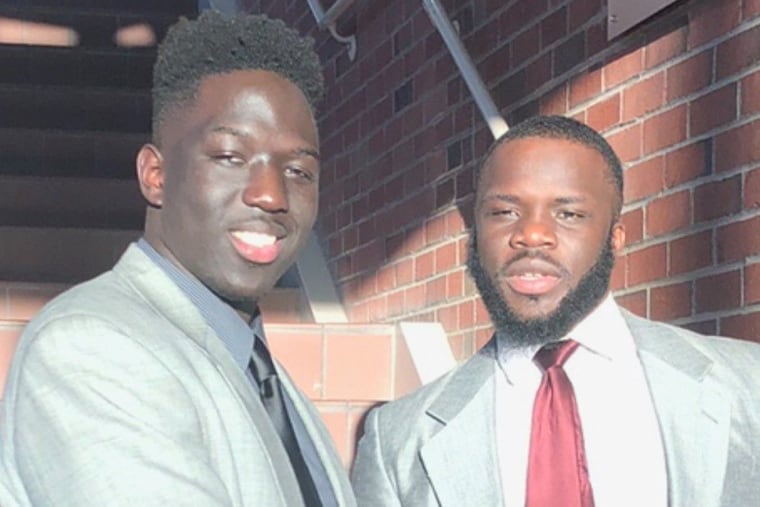

The rally at 5 p.m. Tuesday at LOVE Park will be hosted by Diawara and his friend and fellow organizer Joar Dahn, 22, a Liberia native and a former member of the board of governors of Pennsylvania’s State System of Higher Education. About 200 people — victims of gun violence, those who hope to avoid it, those paid to detect and prevent it, and those elected to curtail its effect on society — are expected to attend.

“The biggest thing is we’re either going to stand together as one,” Diawara said, “or we’re going to fall together.”

First came fear

About 9 p.m. June 16, Diawara, a defensive lineman in football set to graduate this month after just three years at Lock Haven University, left Finnegan Playground — the park he grew up near in Southwest Philadelphia — and headed for his job working security at a nearby nightclub.

Shortly after he arrived for his 9:45 p.m. shift, the 2016 Prep Charter grad saw an Instagram post about a shooting in Southwest Philly.

Then another post. Then another.

“Social media was going crazy,” Diawara recalled as he sat inside the office of Focused Athletics, a nonprofit at 16th and Walnut Streets that benefits athletes in the region.. “I was swiping up on Instagram stories, trying to figure out what was going on.

About 15 minutes later, family members responded via text that they were safe.

Mohamed, 18, a recent Boys’ Latin graduate slated to play football at Bates College in Maine, and Diawara’s youngest brother, Ibrahim, 14, who will be a sophomore in the fall at Boys’ Latin, were both safe.

“That 15 minutes felt like an hour,” Diawara said.

Police later said the shooting happened at 10:08 p.m. at 6801 Grovers Ave. in Southwest Philly when “a suspect shot indiscriminately into the crowd.”

Isiaka Meite, 24, was shot in the back and later died at Penn Presbyterian Medical Center, according to police.

A motive, police said, was “unclear.” No arrests had been made as of Monday.

Five people were wounded in the shooting, including the teenage cousin of Dahn’s and another teenager who was a childhood friend of Ibrahim Diawara’s.

“He’s been sheltered as much as possible to stay away from everything,” Diawara said of Ibrahim. “… and [it’s difficult] to say that he had to hear people shooting … and he had to just run blindly, trying to get away.”

“It’s as frustrating as it gets,” Diawara said. “I feel like any violence is too much violence in the city. You’re trying to do everything the right way, not selling drugs, not shooting people, not robbing people, and people still find you with this stuff.”

Frustration had been building

Even before Dahn set foot in America, Philadelphia’s gun violence already had traumatized him.

In the 1990s, years before he was confirmed by the state Senate to sit on the board of governors of the higher education system, his father, Arthur, had traded civil war in Liberia for Philadelphia, leaving his family in Africa so he could find work in America, save money, and send for them later. In 1999, Arthur called home with news that he had been robbed at gunpoint near 56th Street and Whitby Avenue around 5 a.m. while on his way to work.

Dahn and his mother, Josephine, and younger brother Josephus, wouldn’t make it to America until 2006.

A few years after he arrived in the United States, Dahn said, he also was robbed at gunpoint near Island Avenue in Southwest Philly.

He eventually wrestled, played football, and ran track at Roman Catholic High School, where he graduated in 2015. Dahn, who had spoken little English when he arrived in America, earned a full academic scholarship to Bloomsburg University.

His brother Josephus, now 20, graduated from Roman in 2016 and is a defensive back at Delaware State University.

Dahn served as the university’s student government president as a junior and senior. He also chaired the state higher education system’s Board of Student Government, composed of other student government presidents at universities across the state.

On May 11, Dahn graduated with a degree in political science. Two days later, he celebrated his 22nd birthday.

On June 16, he ran for his life.

“At first,” Dahn said, “I’m thinking it was just fireworks. Then I saw people just dropping.”

Dahn had been the chaperone that night, driving his younger cousins to the celebration at Finnegan Playground.

One of his cousins, he said, was wounded but has since left the hospital and is recovering.

Refusal to give up

When he was a high school sophomore, Diawara said, a man pulled a knife and tried to rob him not far from his home in Southwest Philly.

The event was traumatic, he said, but Diawara didn’t let it stop his pursuit of the American dream his parents had sought for him.

Now 55, Mamadou Diawara left a career as a teacher in Mali so his wife and future children could have a better life in America, Diawara said.

Mamadou had earned a degree in physics in Africa. When he arrived in America in his mid-20s, however, he made about $3 an hour in cash working at a car wash.

Years and several jobs later, he saved enough money to send for his wife, Djita, who also went to work after she arrived here.

Now their son, who learned English as a child by watching PBS, will graduate from college in July and then pursue a master’s in business at Division II Lake Erie College, in Ohio, where he also will finish his final two years of football eligibility.

His older brother, Omar, 24, was a standout athlete in track and soccer at Albright College. Mohamed received a full academic scholarship to Bates, a private, liberal arts school that costs $73,000 per year.

“I couldn’t be more grateful,” Cheick Diawara said. “For the sake of giving us a better opportunity, [our parents] brought us here. [They] could have lived a comfortable, complacent life” in Africa.

In his parents’ spirit of giving, Diawara said, he hopes to give peace of mind back to his younger brother, Ibrahim.

“I refuse for my little brother and his friends to not feel safe going to the park,” Diawara said.

Family deserves peace

Djita Diawara, 44, isn’t ready for her youngest son, Ibrahim, to be interviewed about his experience fleeing bullets at Finnegan Playground.

She was in France on June 16, flown there by relatives for a niece’s wedding. She ended that trip early and returned to Philadelphia, the city in which she had settled when she was around 17.

“We have tried to make the children understand that if you make it in life,” Djita Diawara said, “you have to go back and help other people in need, too.”

Perhaps that’s the most important reason Cheick Diawara walked into City Hall without an appointment June 17 and asked how he could organize a rally.

Organizing events at Lock Haven and serving as vice president of both the Multicultural Advisory Council and the Black Student Union certainly helped.

So did guidance from City Council members Mark Squilla

and Kenyatta Johnson, Diawara said.

The two politicians and law enforcement officials are expected to attend the rally, Diawara said.

Mayor Kenney is expected to speak at the rally.

Diawara and Dahn also contacted civic-minded organizations that will disseminate information about services they offer.

According to both men, their efforts stem from the importance their West African cultures place on community.

“Regardless of how well we all know each other,” Diawara said, their cultures “are really family-oriented. It really takes a village, and that’s what I’m trying to bring here. As a village, we all need to come together right now, find a feasible solution, and squash [the violence] now.”

Staff writers Chris Palmer and Mensah M. Dean contributed to this article.