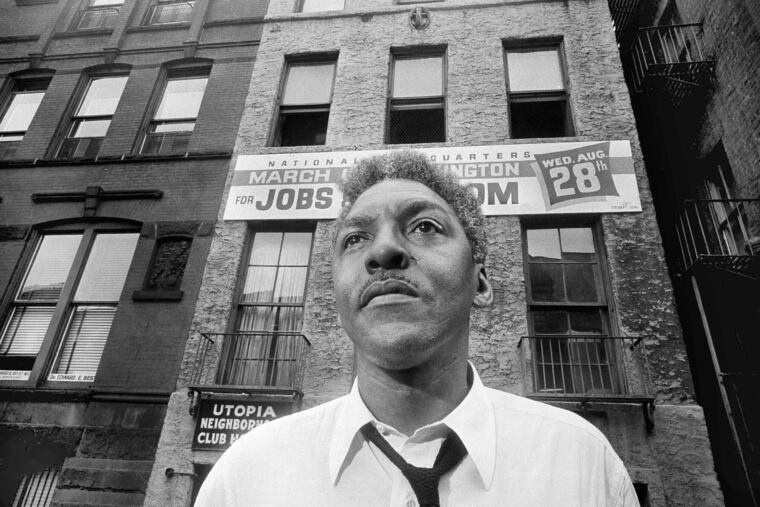

Pa. civil rights icon Bayard Rustin gets posthumous pardon

He was convicted for homosexual activity under outdated laws.

Bayard Rustin, a gay civil rights icon with Philadelphia-area roots and a confidante of the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and who was convicted for homosexual activity under outdated laws, has been posthumously pardoned by California Gov. Gavin Newsom.

Rustin was born in West Chester in 1912, where he grew up to lead nonviolent protests and learn the Quaker principles that propelled his activism. He was a key organizer of the historic 1963 March on Washington, protested Chester County’s segregation in local theaters and lunch counters, and participated in one of the first Freedom Rides.

Rustin, who died in 1987 and was honored by then-President Barack Obama with the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 2013, had counseled King on the principles of nonviolence.

He was arrested on more than one occasion — spending more than two years in jail after protesting Japanese internment camps during World War II, and then arrested and beaten during the 1961 Freedom Rides — but it was his 1953 arrest in California that shaped the rest of his life.

Rustin was found having sex with two men in the backseat of a car in Pasadena, where he was appearing as part of a lecture tour on anti-colonial struggles in West Africa. He served 50 days in Los Angeles County jail and was forced to register as a sex offender. The arrest prompted his religious and political associates to distance themselves, California legislators who advocated for the pardon said.

On Wednesday, Newsom pardoned Rustin and issued an executive order for a new initiative to identify others who were incriminated by outdated homophobic laws and might be eligible for pardons. At the time of Rustin’s arrest, police and prosecutors nationwide used charges like vagrancy, loitering, and sodomy to punish LGBTQ people, the governor noted.

Rustin “is far from alone,” Newsom said in the order. He encouraged others in similar circumstances "to seek a pardon to right this egregious wrong.”

Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Wolf commended Newsom’s pardon on Twitter Thursday morning.

Rustin never hid the fact that he was gay. But his sexual orientation and his belief in the Quaker principle of humility kept him out of the movement’s spotlight, John D’Emilio, author of The Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin, told the Inquirer in 2013.

He attended the segregated Gay Street School and later West Chester High School, which was integrated because there were not enough black students to fill a separate school. He later studied at what is now Cheyney University.

As a teen, Rustin sat in the white section of Warner Theater to protest segregation. He frequently returned to West Chester from his home in New York to attend rallies and speak on behalf of racial equality.

Bayard Rustin High School in the West Chester Area School District is named for him.

The Associated Press contributed to this report.