A Chesco man’s heart stopped. His wife’s fast response — and a steady 911 dispatcher — saved him.

A couple's 42-year love story continues on, after her faith, a 911 dispatcher's calm, and quick response from EMS. Cardiac arrest is "100% fatal" if no one intervenes.

Bob Borzillo has a deal with his wife Terri: She puts everything in the dishwasher, but he has to unload it.

That’s what he was doing on a night in November, after the couple had arrived back home in Willistown from Barcelona. He was putting the very last thing — a wine glass — away. That’s where the 65-year-old’s memory stops.

But for Terri Borzillo, also 65, that’s where a terrifying ordeal began.

She had been just a few feet away, writing in her journal as her husband unloaded the dishwasher in the background. She heard him groan and glass shatter. She got up to help him, expecting to find him picking up glass shards. Instead she found him on the floor, unresponsive.

What they did not know then was that a piece of plaque had broken off, completely blocking his artery. He was in cardiac arrest — not breathing, no pulse. After having walked around Barcelona, averaging 18,000 steps a day, he had no symptoms, no warning signs, until he collapsed in their kitchen.

More than 350,000 people annually experience cardiac arrest outside hospitals, and only one in 10 survives, said Jeffrey Salvatore, the vice president of community impact for the American Heart Association of Greater Philadelphia.

The association has been leading a campaign to teach more teens and adults hands-only CPR to increase bystander response rates. Nationally, 40% of those who experience cardiac arrest each year are helped by a bystander. The rate in the Philadelphia region is significantly lower: less than 26%.

» READ MORE: Only 1 in 10 people survive cardiac arrest. Here’s how to help if you’re a bystander.

The association also holds telecommunicator CPR training, so dispatchers can instruct people over the phone on how to provide CPR, said Salvatore.

“Cardiac arrest is 100% fatal without any intervention. If nobody does anything for the person, there’s no chance of survival,” he said. “By just calling 911 and just doing compressions, you can still double someone’s chance of survival.”

Terri Borzillo immediately went into action, calling 911.

“I think my husband’s having a heart attack,” she remembers screaming to the dispatcher.

Calmly, the Chester County dispatcher, Kayla Wettlaufer, had Borzillo describe her husband’s condition.

“She said, ‘OK, lady, get control of yourself. We’re going to do this together,’” Borzillo recalls. “By the command in her voice, and because there was no option, I had to do this.”

Wettlaufer led Borzillo through CPR over the phone — telling her where to place her hands, when to compress. Wettlaufer even told her when it was time to unlock the front door so the nearby first responders could get in.

“It was horrible to watch my husband in that condition, and it was horrible to know that I had the balance of his life in my hands,” Borzillo said.

With Wetlaufer guiding her — and, she swears, every doctor in heaven — she did compressions until the EMTs arrived, using paddles to restart his heart.

As the EMTs wheeled Bob Borzillo out, Terri Borzillo retrieved the bottles of holy water they had picked up at Our Lady Lourdes in Barcelona. She sprayed her husband and the EMTs.

It got her an odd look, but, she said, “For somebody who has deep faith, I know all the angels and saints were there with us, and we’re smiling today instead of crying,” she said.

Terri Borzillo’s faith runs back to their first date, more than 40 years ago. It was 1982, she was single, and her coworker asked her if she’d like to meet a nice guy. What do I have to lose? she thought. Acting as an intermediary, that colleague — a friend of Bob Borzillo’s family — told Bob about Terri. The young man’s father happened to know Terri’s father. He told his son, “Call that girl.” Bob listened.

On their blind date, Terri Borzillo knew he was the one. There was something to how he talked, explaining — of all things — turbine generators.

He really was a nice guy, she thought. (“I was a nerd,” he said.) She felt something click. Dear God, she thought, let him ask me out again.

One big Italian wedding, three sons, and seven grandchildren later, the two have lived in Chester County for more than 40 years.

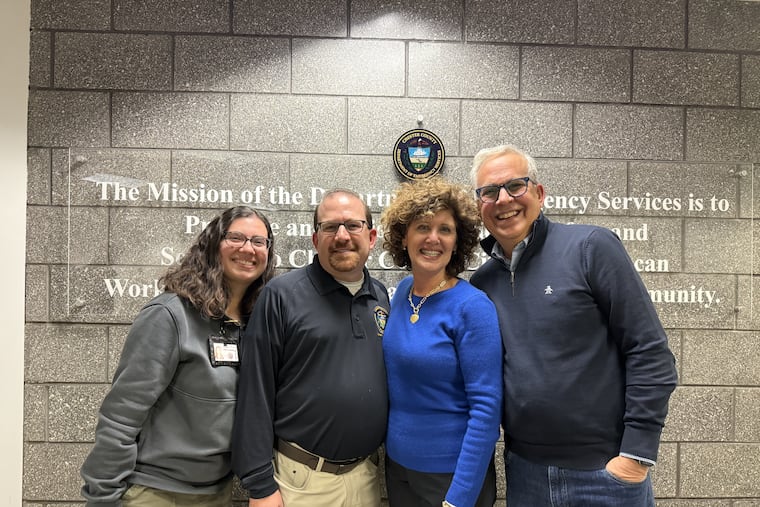

This experience has made him proud to be a county resident, Bob Borzillo said. After he was released from the hospital a few days later, Borzillo went to the firehouse and met the first responders. He and his wife met Wettlaufer, and toured her workplace.

Wettlaufer, an operator who has been with the county for almost five years and was honored by the county this month, was the start of a well-oiled machine, Borzillo said. Their proximity to the firehouse and Paoli Hospital helped get him professional care quickly.

“If the Eagles offense executed that efficiently, we would have been in the Super Bowl,” he said.

Terri Borzillo said meeting Wetlaufer helped ease the trauma of the situation.

“She’s beautiful. And what they do there is amazing, and they get all of the credit,” she said.

Saturday marks three months since Bob Borzillo’s cardiac arrest. He and his wife are in Florida while he recovers, and will celebrate Valentine’s Day with friends from Chester County.

“Certainly the heart and what Valentine represents has a special meaning this year, and I am blessed to be here to celebrate it,” he said in an email.

This suburban content is produced with support from the Leslie Miller and Richard Worley Foundation and The Lenfest Institute for Journalism. Editorial content is created independently of the project donors. Gifts to support The Inquirer’s high-impact journalism can be made at inquirer.com/donate. A list of Lenfest Institute donors can be found at lenfestinstitute.org/supporters.